The awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model of the food safety compliance: the case of street food consumers in Manila City, Philippines

Highlight box

Key findings

• Most of the 384 street food consumers in the Philippines have a good level of awareness, agreement, and adherence to the food safety policy.

• Ninety-four of 384 (24.5%) street food consumers deviated from the awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model.

• The consumers’ agreement with the food safety policies accounts for 77.4% of the variance in adherence, while awareness accounts for 21.9%.

What is known and what is new?

• Street food vendors and other food handlers play a critical role in ensuring food safety for consumers. Numerous works of literature discuss the weaknesses and opportunities in enforcing food safety compliance among food handlers.

• The consumers play a role in food safety. This study revealed that consumer awareness alone does not guarantee agreement and adherence. The progression from awareness to agreement to adherence, with adherence as the ultimate goal, is heavily influenced by consumer agreement.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Food safety policies must be followed by both food handlers and consumers. Building consumer confidence in the food regulatory system and encouraging their participation in risk communication are essential. The awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model explains how an information campaign can lead to consumers adhering to food safety policies. Additionally, government investment in improving the education of Filipinos would not only benefit the country’s workforce and economy but also empower individuals to make informed decisions about their health, such as following the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 when consuming street food.

Introduction

Background

Approximately 600 million people, which is nearly 1 in 10 individuals worldwide, become sick as a result of consuming contaminated food. This results in the annual death of 420,000 individuals, equating to a burden of 33 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (1). Food contamination causes foodborne illnesses and can occur anywhere along the food manufacturing, distribution, and consumption chain. The Pan American Health Organization and the World Health Organization (WHO) have identified five factors that contribute to these illnesses: the use of unsafe water and ingredients in food preparation, unhygienic conditions for food workers, improper cooking techniques, improper storage temperatures, and cross-contamination between raw and fresh, ready-to-eat meals (2).

Street food consumption is a major public health concern due to the numerous food safety hazards associated with it, as well as the insufficient measures in place to ensure food safety (3,4). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines street food as affordable and easy to consume ready-to-eat foods and beverages sold by vendors on the streets and in other public places (5). With its convenience and affordability, an estimated 2.5 billion people worldwide consume street food on a daily basis (4). However, regulating the hygiene and sanitation of public places where street food is sold and consumed can be challenging. It is crucial for public health authorities to implement regulations to prevent the spread of foodborne pathogens. For instance, improper storage and reheating practices in street food vending can increase the risk of heat-stable toxins produced by the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium perfringens. Crowded places like roadside locations, where street food vendors are usually found, make it easier for pathogens like Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli to be transmitted from person to person (6).

There is a policy foundation that regulates food safety in the Philippines. Republic Act 10611, the Food Safety Act of 2013, the Code on Sanitation of the Philippines, and the long-standing technical committee that led to the development of food safety standards in the country are just a few of the regulations implemented in the country (7). These policies need to be strengthened with the ongoing urbanization in the country. Urbanization and population growth are the main factors contributing to the rapid growth of street food vending (3). While food vendors play a critical role in food safety, the consumer’s awareness, agreement, and adherence to food safety in general also play a pivotal role in controlling foodborne diseases (4,8-10).

Rationale and knowledge gap

The majority of published literature on food safety compliance primarily focuses on food handlers. However, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the successful implementation of food safety policies, it is necessary to examine the entire street food consumption system (4,8). In terms of consumer involvement, most literature examines consumer awareness, attitudes, behavior, and practices related to food safety in general, with a primary focus on food safety at home (10-13). Yet, there is a lack of studies or reports on food safety compliance among consumers of street foods. These records are essential for better understanding of the existing issues and challenges in food safety management regarding street food consumption.

Objective

This study aims to assess street food consumers’ awareness of the food safety based on the Philippine Food Safety Act of 2013 and how it influences their agreement and adherence. It is important for consumers to be aware of food safety policies to ensure food safety. However, their role extends beyond awareness of rules and regulations. Consumers also need to have the same level of capacity as producers when assessing the safety of food consumption, considering their preferences, habits, and decision-making processes. In addition, the Philippines has other local guidelines, rules, and regulations related to food safety. Experts at the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies view this multiplicity of standards as a hindrance to effective implementation of food safety policies (14). This study views consumers’ agreement with and adherence to food safety policies as a decision to actively participate in ensuring the safety of street food consumption. The findings of this study can be used by public health authorities to review and enhance the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of food safety campaigns in the country.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study design was used in this study. It is a type of observational study design that provides data for describing the status of a phenomenon at a single point in time (15). In the absence of access to the potential respondents for an extended period, the cross-sectional study design seeks to answer all the questions at once.

Sampling site

The study was strategically conducted in three locations across the city of Manila. The first site is located on R. Papa Street in Sampaloc, Manila, where the well-known “hepa lane” can be found. Although the term “hepa lane” is commonly associated with this specific street in Sampaloc, Manila, it is also used to refer to other locations with an entire street lined with street food vendors. Quinta Market in Quiapo, Manila, and Teresa Street in Sta. Mesa, Manila were the other two research sites for this study. The term “hepa lane” is derived from two words, hepatitis, and lane. In urban Philippines, it is widely believed that consuming street food can increase the risk of transmitting the hepatitis A virus (HAV) due to inadequate food safety measures.

Sampling technique, population, and sample size

This study used non-probability sampling, a technique that involves a non-random selection. This technique is most useful for studies where it is impossible to draw a random probability sample due to time and cost constraints (16). Estimating the population size to create a random sample of street food consumers in R. Papa Street in Sampaloc, Quinta Market in Quiapo, and Teresa Street in Sta. Mesa, Manila would require a significant amount of time and various techniques. Therefore, non-probability sampling was deemed appropriate. In this study, three non-probability sampling techniques were employed. Convenience sampling was used to select respondents who were readily available for an in-person, self-administered survey. The research sites were first visited by the researchers to determine the days and times with high foot traffic. This information helped estimate the speed of data collection, cost-effectiveness, and availability of respondents. Snowball sampling was also utilized, which involves recruiting initial participants who then refer additional participants from their social network. This creates a “snowball” effect that gradually increases the sample size (17). During the process, respondents from the convenience sampling made referrals to other eligible respondents. Eligible respondents included individuals who were 18 years old and above, street food consumers in any of the three research sites, and willing to provide informed consent. Respondents who were willing to make referrals were given a calling card to schedule an in-person survey and a link/QR code to an online questionnaire. Lastly, the researchers determined a quota of samples by calculating it based on an infinite population, as there was no known record of the number of street food consumers in the research sites. When calculating the sample size, a margin of error (e) of 0.05 or 5% and a standard deviation (p) of 0.5 were chosen to ensure a representative sample. To achieve a 95% confidence level, a z-score of 1.96 was used. Below is the formula used to compute samples from either an unknown or very large population (18).

The population was divided into specific groups based on sex, male and female. The quota of samples, based on respondents’ sex, was determined using the proportion of males to females in Metro Manila based on the 2020 census. According to the 2020 census conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the population of Metro Manila was 13,484,462, with 49.2% males and 50.8% females (19). Based on this computation, this study required 189 (49.2%) of the 384 respondents to be male, while 195 (50.8%) of the 384 had to be female.

Research instrument

A self-administered questionnaire used in this study was based on the questionnaires developed by Ma et al. (20), Odeyemi et al. (12), and Samapundo et al. (21). The modifications were done to ensure the appropriateness of the instrument in answering the research questions posed in this study. The questions are composed of recall and recognition-type inquiries to supply all the information the respondents need. Closed-ended questions were written in English and Filipino to provide options for the respondents. The self-administered questionnaire is divided into four parts. The socio-demographic section covers the respondents’ name (optional), age, sex, civil status, and highest educational attainment. Regarding the respondents’ awareness of food safety, 15 statements were asked to be rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The 15 statements were based on the Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611). The next portion of the questionnaire presents 15 statements measuring how the respondents agree to the Act’s salient points and the other 15 statements measuring their compliance or adherence to the food safety. These parts of the questionnaire also have a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire was subjected to experts’ validation and reliability testing. The internal reliability of the instrument was ‘good’ at Cronbach’s α=0.84 (22).

Data-gathering procedures

The questionnaires were disseminated to all available respondents in the study areas. The three sampling techniques were maximized to reach the quota needed for acceptable statistical analysis. The respondents had an option to voluntarily participate in the study or not after explaining the objectives of the survey. The Consent Form, which states the background of the study, its concept and objectives, and other pertinent disclosure statements, was first signed by the respondents before completing the self-administered questionnaire. In some cases, the respondents requested the investigators to read the questionnaire out loud and fill it out for them. It was permitted in this study. The data collection started in December 2022 and was completed in February 2023.

Statistical treatment for data analysis

The respondents’ responses were entered into MS Excel by the two investigators. After cleaning the data sets, they were transferred to Statistical Package for Social Science Version 28 (SPSS 28) for analysis. Descriptive analysis was applied to calculate the means, frequency, percentage, and standard deviation. For the age category in the socio-demographic profile, the age ranges were 18–30 years old (young adults), 31–45 years old (middle-aged adults), and 46 years old and above (old-aged adults).

Point acquisition was used to obtain the total scores of the respondents on the three sections of the questionnaire. In the ‘awareness’ section, all items are positive statements except for items 8 and 9, which are negative or reverse statements. Therefore, items 1 to 7 and 10 to 15 are positive statements and were given 1 point as a correct answer only if the respondents selected 4 and 5 on the Likert Scale. Items 8 and 9, on the other hand, are negative statements and were given 1 point as a correct answer only if the respondents selected 1, 2, and 3 on the Likert Scale. Otherwise, 0 points were obtained. This type of computation was also used in the ‘agreement’ and ‘adherence’ sections. The obtained points for the three sections of the questionnaire were converted into percentages and subjected to cut-off points suggested by Bloom, which are widely used in various public health research (23-25). Poor level of awareness, agreement, and adherence ranges from ≤59%; moderate level ranges between 60% and 79%; good level ranges from 80% to 100%.

The Mann-Whitney U-test and Kruskal-Wallis test (26) were used to test the hypotheses associated with the significant differences between the socio-demographic profiles and the awareness, agreement, and adherence of street food consumers on food safety. Simple linear regression analysis was also computed to determine the association between awareness, agreement, and adherence. The significant differences in the data were set at a 95% confidence interval, where α=0.05 or P<0.05.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted following the guidelines of the University Research Ethics Board of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (UREC Code: UREC-2022-0161) and the principles outlined in the current version (2013) of the Declaration of Helsinki. The consent form provided a clear explanation of the study’s objectives, methodology, and procedures. The respondents were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality, which were rigorously upheld. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Results

Socio-demographic profile of the respondents

A total of 384 respondents properly answered and completed the questionnaire, making their responses eligible for the subsequent statistical analysis of data. The data from three sampling sites were combined for the analysis of the socio-demographic profiles of the respondents. The frequency and percentage distribution of the respondents according to their socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–30 years old (young adults) | 346 (90.1) |

| 31–45 years old (middle-aged adults) | 21 (5.5) |

| 46 years old and above (old adults) | 17 (4.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 189 (49.2) |

| Female | 195 (50.8) |

| Highest educational attainment | |

| Elementary | 3 (0.8) |

| Junior high school | 10 (2.6) |

| Senior high school | 55 (14.3) |

| College undergraduate | 224 (58.3) |

| College graduate | 92 (24.0) |

| Civil status | |

| Single | 344 (89.6) |

| Married | 38 (9.9) |

| Annulled/divorced | 0 (0.0) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.5) |

The quota sampling required a proportion of 49.2% males and 50.8% females. Out of the 384 respondents, 195 (50.8%) were females, and 189 (49.2%) were males. The distribution of male and female respondents adhered to the quota set in this study. In terms of age, 346 (90.1%) of the 384 respondents were between 18 and 30 years old (young adults), 21 (5.5%) were between 31 and 45 years old (middle-aged adults), and 17 (4.4%) were 46 years old and above (old adults).

Regarding the highest educational attainment, most respondents (n=224; 58.3%) had attained college education at the time of data collection. A total of 92 respondents (24%) had graduated from college, 55 (14.3%) had completed senior high school, 10 (2.65%) had completed junior high school, and 3 (0.5%) had completed elementary education. In terms of civil status, 344 (89.6%) out of the 384 respondents were single, 38 (9.9%) were married, and 2 (0.5%) were widowed. No data were obtained from any respondents who were possibly annulled/divorced.

Awareness, agreement, and adherence of the respondents to the food safety as stipulated in the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611)

The scores of the respondents on the 15 awareness statements, 15 agreement statements, and 15 adherence statements were computed. The respondents were grouped into categories of good, moderate, or poor awareness, agreement, and adherence to the food safety using the cut-off points suggested by Bloom (23-25). The majority of the 384 respondents demonstrated a consistently good level of awareness, agreement, and adherence to food safety. Out of the total respondents, 315 (82.0%) had a good level of awareness, 45 (11.7%) had moderate awareness, and 24 (6.3%) had poor awareness. Meanwhile, the number of respondents with a good level of agreement was higher compared to the number of respondents with a good level of awareness, with 361 (94.0%) highly agreeing with the statements on food safety stipulated in the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611). Similarly, there were more respondents with a good level of adherence (n=339; 88.3%) compared to the number of respondents with a good level of awareness.

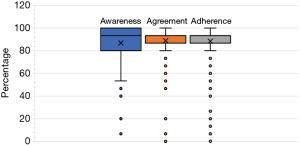

A box and whisker plot (Figure 1) is used to present the three variables, allowing for a comparison of data distribution and identification of any outliers. The level of awareness shows more variation among the respondents compared to agreement and adherence. It ranges from a minimum score of 53% to a maximum score of 100%. On the other hand, agreement and adherence have different outliers but share the same maximum and minimum scores of 100% and 80%, respectively. The box and whisker plot also reveals a higher statistical dispersion in the level of awareness [interquartile range (IQR), 20%] compared to the level of agreement (IQR, 6.7%) and adherence (IQR, 6.7%).

Awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence models on food safety as stipulated in the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611)

The awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model is defined in this study as a cascading effect, wherein a good level of awareness leads to a good level of agreement and adherence. Figure 2 illustrates the different paths of awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence regarding food safety among street food consumers, as stated in the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611). Out of the total respondents, 290 (75.5%) aligned with the model, while 94 (24.5%) deviated from it. Six types of deviations were observed, including cases where respondents had good awareness and agreement, but lacked adherence (poor). This is classified as good-good-poor (n=12; 3.1%). Other deviations include good-poor-good (n=7; 1.8%), good-poor-poor (n=6; 1.6%), poor-good-good (n=45; 11.7%), poor-good-poor (n=13; 3.4%), and poor-poor-poor (n=11; 2.9%).

Associations between awareness-adherence and agreement-adherence

The end goal of various information and awareness campaigns is for the people’s adherence. This paper also intends to reveal the influence of people’s ‘awareness’ to their ‘adherence’ to the food safety and the influence of the people’s ‘agreement’ to their ‘adherence’. Figure 3 presents the scatter plot of the regression analysis conducted.

Regression analysis revealed that adherence to food safety has a significant positive association with awareness (B=0.219, P value =0.01) and agreement (B=0.774, P value =0.006) with food safety as stipulated in the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 (RA 10611). The awareness of food safety accounts for 21.9% of the variance in adherence, t(1, 384) =6.194, P value =0.01, while the agreement accounts for 77.4% of the variance in adherence, t(1, 384) =14.346, P value =0.006.

Significant differences between the street food consumers’ awareness, agreement, and adherence to food safety, based on the respondents’ socio-demographic profile

Socio-demographic profiles are vital in understanding the levels of awareness, agreement, and adherence of street food consumers toward food safety. Analyzing these profiles enables policymakers and public health administrators to design tailored interventions against foodborne diseases. Table 2 presents the association between the respondents’ levels of awareness, agreement, and adherence toward food safety and their age, sex, highest educational attainment, and civil status.

Table 2

| Socio-demographic profile | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Agreement | Adherence | |

| Age | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.09 |

| Sex | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.08 |

| Highest educational attainment | 0.004* | 0.001* | 0.01* |

| Civil status | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0.30 |

*, significant at P value ≤0.05.

Regarding the respondents’ age, the street food consumers’ level of awareness had a K-statistics of 3.482 with a P value of 0.18. This is not a significant value. The same result was observed in the respondents’ agreement (K-statistics =0.124, P value =0.94) and adherence (K-statistics =4.750, P value =0.09). This implies that when the respondents were grouped according to their respective age group, their awareness, agreement, and adherence toward food safety differed insignificantly. Sex is another socio-demographic characteristic not associated with street food consumers’ awareness, agreement, and adherence toward food safety. The analyses of data resulted in a U-statistics of 17,943.5 with a P value of 0.66 for the knowledge, U-statistics =18,097.5, P value =0.76 for the agreement, and U-statistics =16,499.5, P value =0.08 for the adherence. Like the age, when the respondents were grouped according to their respective sex, their awareness of food safety differed insignificantly.

It is shown in Table 2 that the educational attainment of the street food consumers was associated with their level of awareness, agreement, and adherence toward food safety. The street food consumers’ awareness level based on their highest educational attainment had a K-statistics of 17.223 with a P value of 0.004. In terms of their agreement, the K-statistics is 20.019 and a P value of 0.001, while in terms of their adherence, the K-statistics is equal to 14.989, with a P value of 0.01. These results across the three components of awareness, agreement, and adherence showed the statistical significance of value.

For the civil status, when the respondents were grouped accordingly, no significant difference in their awareness, agreement, and adherence toward food safety was observed. Based on their civil status, street food consumers’ awareness level had a K-statistics of 3.776 with a P value of 0.15. Their agreement had a K-statistics of 0.907 with a P value of 0.64. Their adherence had a K-statistics of 2.406 with a P value of 0.30. The P values were more than 0.05, thus assuming no significance level. The null hypothesis failed to be rejected.

Discussion

The role of consumers in the implementation of the Philippine Food Safety Act of 2013

Republic Act 10611, also known as the Food Safety Act of 2013, is a comprehensive regulatory framework that outlines the responsibilities of government agencies in ensuring the safety of food throughout the entire supply chain. The law aims to address the growing concerns regarding food-borne illnesses and other food-related hazards in the country (7). This Act includes various key provisions including the establishment of regulatory framework for food safety under the supervision of the Department of Health, Department of Agriculture, Food and Drug Administration, and other related agencies. The Food Safety Act of 2013 emphasizes the importance of consumer awareness and education regarding food safety (7). Public health awareness plays a crucial role in promoting the well-being of the community. It encourages individuals to make responsible choices not only for themselves, but also for others. Thus, programs that empower consumers to make informed choices and practices regarding food consumption is highly needed (27).

Some street food preparation, consumption, handling, and vending practices pose a challenge when it comes to ensuring food safety. For example, common issues like the contamination of street food stall countertops, the improper use of reusable utensils, and the mishandling of dipping sauce often go unnoticed by both vendors and consumers (28). These practices carry potential hazards and microbial risks. The irresponsible use of utensils and unsanitary food stall countertops can lead to the leakage of chemicals, which can then result in food poisoning. Furthermore, they create opportunities for food to become cross-contaminated with bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Shigella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus, as human fluids like saliva come into contact with dish cloths, utensils, and table napkins. The sharing of dipping sauce can also be compromised by poor personal hygiene on the part of both vendors and random consumers. Additionally, the fast-paced nature of street food consumption exacerbates the problem of improper food waste disposal and the lack of monitoring of personal hygiene. Inadequate waste disposal attracts flies and cockroaches, which can then transfer bacteria like Salmonella spp. and Vibrio cholerae from the waste to humans (6).

The adherence to food safety is more influenced by the consumers’ agreement than awareness

This study demonstrates that Filipino street food consumers who are aware of Republic Act 10611 are more likely to agree with and adhere to its food safety guidelines. This is evident in the high number of respondents who fit the awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model. However, regression analysis reveals that adherence is influenced more by consumers’ agreement than mere awareness.

Regarding food handlers, a local study in Northwest Ethiopia shows that practicing food safety among street food vendors is influenced by the supervision of health professionals, their work experience, their attitude toward food safety, and their knowledge about food safety (29). However, knowledge about food safety does not always influence proper practices. For instance, in a study about the practices of food vendors in Nigeria, food safety practice was influenced by food safety attitude and not by food safety knowledge (30). These are the same results as a local study among consumers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Proper food safety practices are associated with the right attitudes toward food safety and not with knowledge of food safety (31). In a separate study among consumers in Vietnam, subjective and objective types of knowledge about food safety did not influence proper behaviors related to cross contamination and temperature control in food preparation. These food handling behaviors are influenced by consumers’ trust in the source of information about food safety and their intention to follow food safety guidelines (32).

In relation to the findings of the current study, policymakers and public health administrators should aim to comprehend the factors that drive consumer agreement with the regulations stated in the Food Safety Act of 2013. There are various potential factors that can explain why consumer agreement has a greater influence than consumer awareness when it comes to consumer adherence to food safety policies. Food safety governing bodies can gain insights from Filipinos’ trust in experts rather than the national government’s leadership, which motivated them to follow recommended actions for public health during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (33). Perhaps, the health system in the Philippines needs to continue building public trust after various controversies, such as the alleged clinical malpractice of Dengvaxia, a vaccine for dengue among children that caused vaccine hesitancy among Filipinos (34,35), and the corruption allegations against the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, a government agency responsible for implementing universal health coverage in the country (36,37). The lack of public trust in the health system in the Philippines, which also encompasses food safety policies, can jeopardize the delivery and implementation of the Food Safety Act of 2013. This underscores the importance of having the right and effective organization or agency to deliver public health recommendations, as outlined in the Act. The trustworthiness of these policies and the individuals who convey them to the public through legislation can influence more consumers to agree to them and eventually adhere to proper food safety practices. This cannot be achieved solely by being aware of the rules and regulations they encompass.

Educational attainment as a predictor of awareness, agreement, and adherence to food safety: a story of health inequity

Filipinos, regardless of their level of education, commonly visit a street food vending area that has derogatorily been named “hepa lane”. A study conducted among college students in Metro Manila, Philippines shows that the convenience of readily available street food is a major factor influencing their intention to purchase these foods (38). According to a Filipino lifestyle and culture journalist, street food consumption is deeply rooted in Filipino culture and the nation’s sensibilities (39). Therefore, street food can be considered a way of life in the Philippines, and the food safety concerns associated with it will remain relevant in the country’s public health management agenda.

The implementation of the Philippine Food Safety Act of 2013 is crucial for minimizing the risks of food safety hazards related to the consumption of street food. This study investigates the factors that determine both awareness of food safety and consumers’ agreement and adherence to the food safety. Among socioeconomic characteristics, educational attainment was identified as a significant predictor of consumers’ awareness, agreement, and adherence to the Philippine Food Safety Act of 2013 and the food safety policies it encompasses.

In general, there is a strong and consistent positive association between higher educational attainment and good health outcomes (40). Individuals with lower levels of formal education may face challenges in distinguishing between reliable and unreliable health-related information, which can lead to a decline in health quality (41). Meanwhile, people with higher education have good knowledge of various diseases, make better health decisions, and reduce practicing health-risk behavior. All these behaviors lead to improved health outcomes (40-45). Various health indicators associated with a person’s educational attainment include functional, mental, psychological, and self-rated health (46). In the current study, high educational attainment is regarded as an indicator not only of awareness but also of agreement with and adherence to food safety policies related to street food consumption.

In a different aspect, the association between education and health outcomes can be complex and subject to confounders. The system of mass public education does not provide equal results for everyone. Individuals who face academic challenges are more likely to have lower levels of educational attainment. As a result, their upward mobility is hindered and their overall health status is affected (47,48). Educational attainment as a predictor of a good level of awareness, agreement, and adherence to food safety policies puts those who obtained low-level education at a potential risk of foodborne transmitted diseases. As a result, educational inequality can cause potential gaps in health status in the context of health education among Filipinos. Quality education in the Philippines still needs to be available for low-income Filipinos (49). The persistent sizeable social inequity and chronic poverty coupled with the archipelagic nature of the Philippines, which impinges on the delivery of health resources, are resulting in a large disparity in health status between the poor and the nonpoor in the country (50). The investments in improving the educational attainment of Filipinos could not only benefit the country through an improved work force and economic growth but also produce people who have the ability to choose right decisions for their health—this includes following the Philippine Food Safety Act 2013 in street food consumption.

The need for reinforcement of the food safety education

Food safety hazards continue to be a major public health concern in the 21st century and beyond. As globalization increases, there is a growing demand for a wider variety of foods. This, coupled with the population explosion, has led to the industrialization of agricultural and animal products to meet the rising food demand. Consequently, the global food chain has become increasingly complex, posing challenges to food safety (51). Developing countries often underestimate the extent of the socio-economic costs associated with food safety hazards. Consequently, their investments in remedial and preventative measures, as well as mitigation against foodborne disease outbreaks and food scarcity, are usually insufficient (52). Research conducted in the USA with key food regulatory participants highlighted several issues in ensuring food safety. These issues include the need for more resources for inspections and testing, a lack of funding for consumer education, the absence of established food regulatory structures, and an inability to handle unpredictable challenges in foodborne disease outbreaks, among others (53).

While some aspects of food safety governance face significant challenges, other efforts, such as preventative and intervention measures, need to be mainstreamed. The WHO emphasizes that food safety is everyone’s responsibility (4). It is crucial to have the support of prominent community leaders in incorporating food safety education into national food, nutrition, and public health policies (54). This need was discussed in research conducted among school administrators in Ontario, Canada. An age-based analysis revealed that young people not only have personal needs for food safety information but also play a role in the landscape of foodborne illnesses (55). Additionally, college students demonstrated improved food safety beliefs and knowledge after participating in a food safety educational intervention. Enhancing well-being through education should not be limited to school settings. Community-based food safety interventions are essential for preventing health inequity in the country. Political recognition of these and similar discourses is crucial for the successful implementation of existing food safety policies (56).

Conclusions

Most street food consumers along the infamous “hepa lane” in Manila, Philippines, were aware of the food safety as stated in the Philippine Republic Act 10611 or the Food Safety Act of 2013. This is an Act that aims to guarantee food safety in the country. The respondents’ awareness of food safety influences their agreement and adherence to food safety. However, in terms of adherence, it is influenced more by the consumers’ agreement than awareness. A few respondents needed to fit the awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model, and this group needs intervention to secure food safety among street food consumers in Manila, Philippines. The respondents’ educational attainment was associated with their levels of awareness, agreement, and adherence. While education in the Philippines remains inaccessible for low-income Filipinos, the reinforcement of health education outside the school is a crucial intervention against health inequities, particularly in health education on street food consumption in the country.

Acknowledgments

The investigators wish to thank the local officials and the street food vendors in the research sites who allowed data collection during the business operations. Your participation is instrumental in ensuring the food safety in the street food vending industry.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-182/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-182/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-182/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted following the guidelines of the University Research Ethics Board of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (UREC Code: UREC-2022-0161) and the principles outlined in the current version (2013) of the Declaration of Helsinki. The consent form provided a clear explanation of the study’s objectives, methodology, and procedures. The respondents were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality, which were rigorously upheld. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Food Safety. 2022. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety

- World Health Organization (WHO). Five keys to safer food manual. 2006. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241594639

- Malhotra S. Food safety issues related to street vendors. In: Gupta RK, Dudeja, Minhas S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2017:395-402.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Food safety is everyone’s business in street food vending. 2022. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-NFS-AFS-2022.4

- Food & Agricultural Organization (FAO). Street foods. 2023. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fcit/food-processing/street-foods/en/

- Rane S. Street vended food in developing world: hazard analyses. Indian J Microbiol 2011;51:100-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Republic Act No. 10611. 2013. Accessed: May 22, 2024. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/phi128390.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO global strategy for food safety 2022-2030: towards stronger food safety systems and global cooperation. 2022. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057685

- Hoffmann V, Moser C, Saak A. Food safety in low and middle-income countries: The evidence through an economic lens. World Dev 2019;123:104611. [Crossref]

- Langiano E, Ferrara M, Lanni L, et al. Food safety at home: knowledge and practices of consumers. Z Gesundh Wiss 2012;20:47-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilcock A, Pun M, Khanona J, et al. Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: a review of food safety issues. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2004;15:56-66. [Crossref]

- Odeyemi OA, Sani NA, Obadina AO, et al. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices among consumers in developing countries: An international survey. Food Res Int 2019;116:1386-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bolek S. Consumer knowledge, attitudes, and judgments about food safety: A consumer analysis. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020;102:242-8. [Crossref]

- Prabhakar S, Sano D, Srivastava N. Food safety in the Asia-Pacific Region: current status, policy perspectives and a way forward. In: Sustainable consumption and production in the Asia-Pacific region: Effective responses in a resource constrained world. Hayama: Institute for Global Environmental Strategies; 2010:215-38.

- Ihudiebube-Splendor CN, Chikeme PC. A descriptive cross-sectional study: Practical and feasible design in investigating health care-seeking behaviors of undergraduates. In: Benbow N, Kirkpatrick C, Gupta A, et al. Sage Research Methods Cases: Medicine and Health. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2020.

- Statistics Canada. Non-probability sampling. 2021. Accessed: March 29, 2024. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/edu/power-pouvoir/ch13/nonprob/5214898-eng.htm

- Emerson RW. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research? Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 2015;109:164-8. [Crossref]

- WikiHow. How to Find the Perfect Sample Size for Your Research Study. 2024. Accessed: April 10, 2024. Available online: https://www.wikihow.com/Calculate-Sample-Size?fbclid=IwAR03h3mzLy_frmcGZamM_CpA8rtKj8FZjuwCMkyPu-yR_ryh5FgYpBJCe6M

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Age and Sex Distribution in the Philippine Population (2020 Census of Population and Housing). 2022. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/age-and-sex-distribution-philippine-population-2020-census-population-and-housing

- Ma L, Chen H, Yan H, et al. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of street food vendors and consumers in Handan, a third tier city in China. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Samapundo S, Climat R, Xhaferi R, et al. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Food Control 2015;50:457-66. [Crossref]

- Statistics How To. Cronbach’s Alpha: Definition, Interpretation, SPSS. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/statistics-definitions/cronbachs-alpha-spss/

- Feleke BT, Wale MZ, Yirsaw MT. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards COVID-19 and associated factors among outpatient service visitors at Debre Markos compressive specialized hospital, north-west Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS One 2021;16:e0251708. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akalu Y, Ayelign B, Molla MD. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards COVID-19 Among Chronic Disease Patients at Addis Zemen Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist 2020;13:1949-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seid MA, Hussen MS. Knowledge and attitude towards antimicrobial resistance among final year undergraduate paramedical students at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laerd Statistics. Kruskal-Wallis H Test using SPSS Statistics. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/kruskal-wallis-h-test-using-spss-statistics.php#:~:text=Typically%2C%20a%20Kruskal%2DWallis%20H,commonly%20used%20for%20two%20groups

- Kumar S, Preetha G. Health promotion: an effective tool for global health. Indian J Community Med 2012;37:5-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alimi BA. Risk factors in street food practices in developing countries: A review. Food Sci Hum Wellness 2016;5:141-8. [Crossref]

- Bantie GM, Woya AA, Ayalew CA, et al. Food Safety and hygiene practices and the Determinants among street vendors during the Chain of Food Production in Northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023;9:e22965. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnabas B, Bavorova M, Madaki MY, et al. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food vendors participating in Nigeria’s school feeding program. J Consum Prot Food Saf 2024. doi:

10.1007/s00003-023-01476-3 .10.1007/s00003-023-01476-3 - Moy FM, Alias AA, Jani R, et al. Determinants of self-reported food safety practices among youths: a cross-sectional online study in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. British Food Journal 2018;120:891-900. [Crossref]

- Dang HD, Dam AHT. Determinants of hygienic handling of food by consumers in the COVID-19 pandemic context: A cross-sectional study in Vietnam. Food Sci Technol 2021;42:e30221. [Crossref]

- Ahluwalia SC, Edelen MO, Qureshi N, et al. Trust in experts, not trust in national leadership, leads to greater uptake of recommended actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2021;12:283-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fatima K, Syed NI. Dengvaxia controversy: impact on vaccine hesitancy. J Glob Health 2018;8:010312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Labana RV, Nissapatorn V, Cada KJS, et al. A Cross-sectional Analysis of Facebook Comments to Study Public Perception of the Mass Drug Administration Program in the Philippines. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021;10:266-72. [PubMed]

- Romero P, Nonato V. PhilHealth Officials Face P15-Billion Fraud, Other Allegations; Funds Seen To Run Out By 2022. 2020. Accessed: March 30, 2024. Available online: https://www.onenews.ph/articles/philhealth-officials-face-p15-billion-fraud-other-allegations-funds-seen-to-run-out-by-2022

- Del Mundo JS. PhilHealth’s road to regaining Filipinos’ trust. 2022. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.bworldonline.com/opinion/2022/09/26/476695/philhealths-road-to-regaining-filipinos-trust/

- Tacardon ER, Ong AKS, Gumasing MJJ. The Perception of Food Quality and Food Value among the Purchasing Intentions of Street Foods in the Capital of the Philippines. Sustainability 2023;15:12549. [Crossref]

- Beltran S. Street food represents the stories of struggle, survival, and a nation’s sensibilities. 2023. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://fnbreport.ph/21158/street-food-represents-the-stories-of-struggle-survival-and-a-nations-sensibilities/

- Eide ER, Showalter MH. Estimating the relation between health and education: What do we know and what do we need to know? Econ Educ Rev 2011;30:778-91. [Crossref]

- School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University. Education as a Social Determinant of Health. 2021. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://publichealth.tulane.edu/blog/social-determinant-of-health-education-is-crucial/

- Altindag D, Cannonier C, Mocan N. The impact of education on health knowledge. Econ Educ Rev 2011;30:792-812. [Crossref]

- UNESCO. What you need to know about education for health and well-being. 2023. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/health-education/need-know

- Hoffmann R, Lutz SU. The health knowledge mechanism: evidence on the link between education and health lifestyle in the Philippines. Eur J Health Econ 2019;20:27-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kenkel DS. Health behavior, health knowledge, and schooling. J Polit Econ 1991;99:287-305. [Crossref]

- Dinwiddie GY. The health advantages of educational attainment. In: Peterson P, Baker E., McGaw B. editors. International Encyclopedia of Education. 3rd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2010:667-72.

- Lynch JL, von Hippel PT. An education gradient in health, a health gradient in education, or a confounded gradient in both? Soc Sci Med 2016;154:18-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Telfair J, Shelton TL. Educational attainment as a social determinant of health. N C Med J 2012;73:358-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). PIDS study outlines inequality in pursuing quality education. 2022. Accessed: October 15, 2023. Available online: https://www.pids.gov.ph/details/news/in-the-news/pids-study-outlines-inequality-in-pursuing-quality-education

- Ortiz D, Picazo O, Aldeon M, et al. Explaining the Large Disparities in Health in the Philippines. 2013. Accessed: March 28, 2024. Available online: https://serp-p.pids.gov.ph/publication/public/view?slug=explaining-the-large-disparities-in-health-in-the-philippines

- Fung F, Wang HS, Menon S. Food safety in the 21st century. Biomed J 2018;41:88-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaffee S, Henson S, Unnevehr L, et al. The safe food imperative: Accelerating progress in low-and middle-income countries. Washington: World Bank Publications; 2018.

- Detwiler D. Food Safety and Federalism. 2016. Accessed: October 10, 2023. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/food-safety-federalism-darin-detwiler

- Flint S, Bremer P. Health Education, Information, and Risk Communication. In: Smithers GW. Encyclopedia of Food Safety. 2nd ed. San Diego: Elsevier Inc.; 2024:617-28.

- Diplock KJ, Jones-Bitton A, Leatherdale ST, et al. Over-confident and under-competent: Exploring the importance of food safety education specific to high school students. Environmental Health Review 2017;60:65-72. [Crossref]

- Yarrow L, Remig VM, Higgins MM. Food safety educational intervention positively influences college students' food safety attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and self-reported practices. J Environ Health 2009;71:30-5. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Labana RV, Dolar MV Jr, Ferrer EJJ, Rabago JRC. The awareness-to-agreement-to-adherence model of the food safety compliance: the case of street food consumers in Manila City, Philippines. J Public Health Emerg 2024;8:13.