Different views on emergency team management according to polish medical professionals

Highlight box

Key findings

• Paramedics as team leaders rarely rush others, shout or curse in comparison with hospital team leaders (physicians).

• There is a potential positive influence of debriefing which is performed more often by prehospital teams.

• Shouts and curses made by physicians are reported with higher incidence by their team members than by leaders.

What is known and what is new?

• Excessive stress in emergency medicine is correlated with worse performance but there is a lack in studies concerning ethical/unethical leadership and its influence on team members.

• This manuscript shows how team leaders and team members describe ethics of leadership, how often unethical phenomena take place.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• There is a need for discussion how to become ethical leader during urgent medical cases. Debriefing should be introduced widely since it seems to improve team cooperation. Further studies should check how unethical leadership influences team members directly.

Introduction

Background

Team cooperation is crucial in management during emergency situations. Team leaders differ in a way they manage. Medical environment as well as available resources affect team leaders’ decisions and behaviour. Team leaders should act with respect and patience with their team members but they also need to ensure efficient and accurate medical aid.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Till this time, we know that team leader’s behaviour influences team members in both positive and negative way (1). It could not only change their level of stress and well-being but also can affect the accuracy/quality of their task outcome. Higher stress level is associated with worse performance especially in emergency medicine (2-5).

There is still an insufficient data on how medical professionals perceive verbal pressure made by team leaders. Particularly, the difference in views of team members and leaders is unknown. These two points of view may give us more clear information if we understand each other in our medical groups during emergency cases.

Objective

Since the emergency team leadership could be performed in many ways what is not indifferent for members, we decided to check differences in medical professionals’ opinions. The aim of this study was to examine if team leaders differ in their team management ways (during urgent cases) depending if they work in prehospital emergency care or hospital facilities [Emergency Department (ED) as well as Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Unit (AICU)]. Especially such features of leadership as verbal pressure (rushing), shouts and curses were examined. Moreover, we decided to check if leaders and members have similar opinion on this issue. We present this article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-180/rc).

Methods

Study design

Online survey was sent to polish medical professionals working in AICU, ED and prehospital emergency care (of different workplaces). No reminders were used. No incentives for participants were provided. One hundred fifty-five replies were obtained and included in further analysis. Only two types of hospital departments were chosen because their teams are highly in common with urgent medical cases. Other units are poorly experienced in this field and they usually ask for help from a resuscitation or rapid response team. Participants were recruited from different workplaces in various regions of Poland so they only constitute samples of leaders and members in general. Differences in views in the same team were not been examined.

Once the survey was opened participants needed to mark if they agree and participate voluntary. The survey consisted of two parts. In the first one participant was asked about such basic information as: age, seniority (years), profession (physician/nurse/paramedic), main workplace (AICU/ED/prehospital) and if they are usually team leaders or team members during medical emergencies. Dependently on their function (leader/member) participants fulfilled different (but similar) second parts of the survey (Table 1).

Table 1

| Question number | Team leaders | Team members |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | How often do you rush team members? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) | How often do experience rushing from your leader? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) |

| 2. | How often do you shout at team members? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) | How often do your leaders shout at team members? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) |

| 3. | How often do you curse? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) | How often do your leaders curse? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘never’, 10 ‘always’) |

| 4. | How do you rate your team management skills? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘very bad’, 10 ‘perfect’) | How do you rate your leaders’ team management skills? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘very bad’, 10 ‘perfect’) |

| 5. | Your composure during medical emergencies? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘very bad’, 10 ‘perfect’) | |

| 6. | Do you think if rushing others is safe for the patient? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘not safe’, 10 ‘very safe’) | |

| 7. | Do you think if rushing others makes people act faster? (0–10 scale; 0 means ‘strongly disagree’, 10 ‘strongly agree’) | |

| 8. | Do you think if rushing others makes people act more effectively? (0–10 scale) | |

| 9. | Do you know the term ‘debriefing’? (yes/no) | |

| 10. | If you know the term ‘debriefing’, how often does your team perform it? (never/rarely/usually/always) | |

| 11. | Do you know the term ‘closed loop communication’? (yes/no) | |

No patients were involved in this study and approval from the Ethics Committee was not necessary, and implied consent was assumed by voluntary response.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed with software Statistic 13. Kruskal-Wallis, U Mann-Whitney and chi-squares tests were used since the data is not parametric. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

Table 2 presents general characteristic of team leaders and team members. Paramedics are team leaders in prehospital emergency care while physicians are leaders in EDs and AICUs. Team members prehospital subgroup consist of only paramedics. ED team members are physicians (especially younger doctors), nurses and paramedics while AICU members are only physicians and nurses.

Table 2

| Question | Team leaders (n=72) | Team members (n=83) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.40±7.93 | 38.39±10.37 | 0.69 |

| Seniority (years) | 13.00±8.01 | 13.13±10.94 | 0.36 |

| Profession | – | ||

| Physician | 27 | 11 | |

| Paramedic | 45 | 30 | |

| Nurse | 0 | 42 | |

| Workplace | – | ||

| Prehospital | 45 | 15 | |

| Hospital-ED | 15 | 39 | |

| Hospital-AICU | 12 | 29 | |

| How often do you rush others/experience rushing from your leader? (0–10 scale) | 2.15±2.25 | 2.41±2.33 | 0.43 |

| How often do you/your leaders shout? (0–10 scale) | 0.42±0.85 | 2.76±2.69 | <0.001 |

| How often do you/your leaders curse? (0–10 scale) | 0.13±0.37 | 1.76±2.35 | <0.001 |

| Your/your leaders’ team management skills? (0–10 scale) | 6.46±1.73 | 5.40±2.49 | 0.003 |

| Your composure during medical emergencies? (0–10 scale) | 7.82±1.33 | 7.06±2.05 | 0.06 |

| Do you think if rushing others is safe for the patient? (0–10 scale) | 1.72±2.04 | 2.24±2.14 | 0.09 |

| Do you think if rushing others makes people act faster? (0–10 scale) | 1.71±2.06 | 1.87±2.03 | 0.54 |

| Do you think if rushing others makes people act more effectively? (0–10 scale) | 1.31±1.74 | 1.51±1.70 | 0.24 |

| Do you know the term ‘debriefing’? (yes/no) | 67/5 | 57/26 | <0.001 |

| If you know the term ‘debriefing’, how often does your team perform it? (never/rarely/usually/always) |

5/18/37/7 | 12/28/15/2 | <0.001 |

| Do you know the term ‘closed loop communication’? (yes/no) | 53/19 | 59/24 | 0.73 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number. AICU, Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Unit; ED, Emergency Department.

Paramedic team members rate their leaders’ management skills (0–10 scale) statistically higher than nurses do (6.23±2.45 versus 4.57±2.15; P=0.01). Moreover, paramedics (team members) report rushing (1.37±1.87 versus 3.40±2.45; P<0.001), shouts (1.97±2.54 versus 3.60±2.71; P=0.01) and curses (0.97±1.97 versus 2.43±2.55; P=0.009) less often than nurses.

EDs leaders rate their team management skills (0–10 scale) statistically lower than prehospital leaders (5.40±1.59 versus 6.80±1.65; P=0.01). Moreover, physicians as team leaders claim to rush others more often than paramedic team leaders do (2.93±2.51 versus 1.69±1.96; P=0.02).

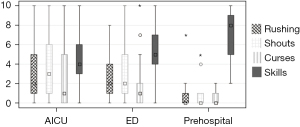

Prehospital team members confess statistically lower rate of verbal pressure, shouts and curses in comparison with hospital team members. Furthermore, prehospital team members evaluate their members’ management skills higher than hospital team members do (Figure 1, Table 3).

Table 3

| Question | AICU versus ED | AICU versus Prehospital | ED versus Prehospital |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you experience rushing from your leaders? (0–10 scale) | 0.97 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| How often do your leaders shout? (0–10 scale) | 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| How often do your leaders curse? (0–10 scale) | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Your leaders’ team management skills? (0–10 scale) | 0.59 | 0.002 | 0.04 |

AICU, Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Unit; ED, Emergency Department.

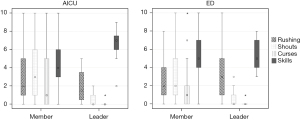

There is no significant difference in frequency of rushing, shouts and curses as well as team leaders’ management skills evaluated by prehospital team leaders and team members. Differences in some of above parameters are present in case of AICU and ED subgroups (Figure 2, Table 4).

Table 4

| Question | ED | AICU | Prehospital |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you rush others/experience rushing from your leader? (0–10 scale) | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| How often do you/your leaders shout? (0–10 scale) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| How often do you/your leaders curse? (0–10 scale) | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.26 |

| Your/your leaders’ team management skills? (0–10 scale) | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

ED, Emergency Department; AICU, Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Unit.

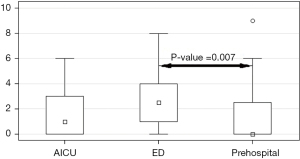

Higher percentage of team leaders knows the term ‘debriefing’ in comparison with team members. Moreover, team leaders report using this tool more often than members notice (Table 2, Figure 3). Chi-square analysis reveals that prehospital medical professionals claim that they perform debriefing always/usually more often than hospital (AICU and ED combined) ones (58.3% versus 27.4%; P<0.001).

There is no difference between subgroups in results of questions: ‘Do you think if rushing others makes people act faster?’ and ‘Do you think if rushing others makes people act more effectively?’.

Prehospital professionals believe more that rushing others influences safety negatively than EDs staff (Figure 4).

Discussion

Key findings

Team leaders and members agree on incidence of team leaders’ verbal pressure while leaders and members do not confess accordingly the incidence of curses and shouts. These last two phenomena could be more embarrassing for leaders.

Team leaders management skills as well as frequency of debriefing are overestimated by leaders in comparison with their team members’ opinion.

Prehospital leaders manage better than hospital ones, they seem to rush others, shout and curse less often as well. They also judge rushing others as less safe. Prehospital team members and leaders are more consistent with their answers than AICU and ED ones.

Strengths and limitations

Number of survey responses is sufficient for reliable analysis and conclusions. The field is in a huge part completely new. The main limitation of our study results from so significant differences between hospital and prehospital teams in general. This is why we cannot conclude if differences in team management are caused mainly by debriefing or other factors distinguishing hospital and prehospital team leaders affect results. There is a need for more studies evaluating if there is a direct influence of debriefing on team leaders’ management patterns.

Comparison with similar researches

There is a lack in debriefing standardized protocols which would be widely used in clinical practice. Every team perform it with their own way and it is hard to compare results. Nevertheless, debriefing is a useful tool which improves team performance (6,7) but it also gives psychological benefits (8-10).

Explanations of findings

Above findings could arise from differences in paramedics and physicians education but it could be associated with higher incidence of debriefing in prehospital subgroups. Paramedics as team leaders are at the same professional level with their team members while physicians usually manage teams consisting of nurses and paramedics (different medical professions). These natural differences in degrees could also lie at the heart of described results.

In general, team leaders do not notice their shouts and curses or they do not confess them.

Implications and actions needed

There is a need for discussion about ethics of team leadership. Medical professionals should get encouraged to perform debriefing more often. It should be investigated in further studies if debriefing is irrespective parameter reducing verbal pressure, shouts and curses.

Conclusions

Prehospital team members and leaders are more likely to be consistent in their teams’ work evaluation. Paramedics as team leaders rarely rush others, shout or curse in comparison with hospital team leaders (physicians). There is a potential positive influence of debriefing which is performed more often by prehospital teams. Shouts and curses made by physicians are reported with higher incidence by their team members than by leaders.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who fulfilled the survey.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-180/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-180/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-180/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-23-180/coif). M.M. reported employment in Powiślańki Univeristy. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. No patients were involved in this study and approval from the Ethics Committee was not necessary, and implied consent was assumed by voluntary response.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Muża M, Kalemba A, Kapłan C, et al. The effect of verbal pressure on students’ performance during simulated emergency situation—a randomized pilot study. J Public Health Emerg 2023;7:25. [Crossref]

- Ignacio J, Dolmans D, Scherpbier A, et al. Stress and anxiety management strategies in health professions’ simulation training: a review of the literature. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn 2016;2:42-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bleetman A, Sanusi S, Dale T, et al. Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2012;29:389-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cumming SR, Harris LM. The impact of anxiety on the accuracy of diagnostic decision-making. Stress and Health 2001;17:281-6. [Crossref]

- Demaria S Jr, Bryson EO, Mooney TJ, et al. Adding emotional stressors to training in simulated cardiopulmonary arrest enhances participant performance. Med Educ 2010;44:1006-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Couper K, Perkins GD. Debriefing after resuscitation. Curr Opin Crit Care 2013;19:188-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cincotta DR, Quinn N, Grindlay J, et al. Debriefing immediately after intubation in a children’s emergency department is feasible and contributes to measurable improvements in patient safety. Emerg Med Australas 2021;33:780-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilmartin S, Martin L, Kenny S, et al. Promoting hot debriefing in an emergency department. BMJ Open Qual 2020;9:e000913. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Twigg S. Clinical event debriefing: a review of approaches and objectives. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020;32:337-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liyanage S, Addison S, Ham E, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent or reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and symptoms among hospital nurses: A scoping review. J Clin Nurs 2022;31:1477-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Muża M, Bornio E, Plata H. Different views on emergency team management according to polish medical professionals. J Public Health Emerg 2024;8:24.