COVID-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: a cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada

Highlight box

Key findings

• Most respondents were unvaccinated and terminated due to mandate non-compliance. Unvaccinated workers reported satisfaction with their choices but faced significant negative impacts on finances, mental health, and personal relationships. Vaccinated respondents often expressed vaccine safety concerns, many experienced adverse events, and some felt coerced into receiving further doses. A large minority of respondents reported issues such as underreporting of adverse events, poorer treatment of unvaccinated patients, and concerning protocol changes.

What is known and what is new?

• Considerable research has examined the perceived problem of vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers (HCWs), and proposed vaccine mandates as a solution for increasing uptake among them. This manuscript adds to the body of existing research on coronavirus disease (COVID) vaccination among HCWs by exploring the lived experiences and views of HCWs about mandated vaccination and about its impact on patient care in Ontario.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This study highlights the need for public health policy to consider the rights to informed consent and bodily autonomy, as well as health system sustainability. It also underscores the need for not only evidence-informed, but also ethics-informed, policies, especially during health emergencies.

Introduction

When coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination policies were introduced in the healthcare sector in the province of Ontario, Canada, tensions regarding mandates for healthcare workers (HCWs) became apparent, especially conflicting opinions regarding their impact on the labour force and patient care. Based on the guidance from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), HCWs, along with other groups designated as high risk, were prioritized for vaccination during “phase 1”—December 2020 to March 2021—of the vaccine rollout in the province (1,2). On August 17, 2021, the Ontario Chief Medical Officer of Health issued Directive #6, a policy that required hospitals and home and community care establishments to implement a COVID-19 vaccination policy for employees, contractors, students, and volunteers. The directive went into effect on September 7, 2021, and remained in effect through March 14, 2022, establishing a mandatory vaccination policy that allowed exemptions to individuals with an officially approved medical waiver or willing to take a test to learn about the ostensible benefits of vaccination before declining (3). Nevertheless, most healthcare settings chose to implement vaccination as a condition of employment, with very limited exemptions, and no test-taking alternative, and the Ontario Ministry of Long-term Care issued a vaccine mandate effective December 2021, also through March 2022, that required all staff, contractors, students, and volunteers, to either be vaccinated or terminated.

While most health professional organizations and regulatory colleges also offered their broad support for vaccination policies, endorsement of mandatory vaccination for HCWs was mixed, with some stakeholders warning about potential negative impacts. Some of the tensions over the introduction of vaccination mandates for HCWs were reported in Canadian media sources (4,5). For example, when in October 2021, Ontario Premier Doug Ford asked for input from health leaders across the province, the Council of Ontario Medical Officers of Health, representing public health officials from the province’s 34 public health units, communicated their approval of a mandatory vaccination policy (5). So did the Ontario Hospital Association, arguing that the policy would increase vaccine uptake, thus making healthcare settings safer (ibid). Supporters also included the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO) that, in an open letter to the Premier, recommended “a clear, comprehensive (and) firm mandate”, because “patients, already vulnerable, (would) have a greater sense of comfort and safety knowing that they (would) not get COVID from (an unvaccinated) HCW”, and because “mandatory vaccination (was) considered by virtually all nurses (…) necessary for the protection of their health and safety and those they go home to every day” (6). RNAO CEO Doris Grinspun, who penned the letter, further proffered that “the absence of mandatory vaccinations is influencing decisions of nurses to leave workplaces and even the profession” (ibid).

From an opposing perspective, the Ontario Nurses Association (ONA) noted that introducing a policy that provided only the option to be vaccinated or terminated, when many nurses were already at their “breaking point”, would “exacerbate an already tenuous situation on the cusp of a catastrophic staffing crisis”, potentially reducing patient safety (5). On a similar vein, as revealed by a freedom of information (FOI) request the following year, the Hospital Notre-Dame CEO cautioned that a vaccine mandate could lead to reduced services, noting that hospital staff were “very well informed...and still choose not to be vaccinated”, and concluding that it would be best to “leave it to the individual hospital to decide” whether or not to mandate vaccination (4). Finally, unions such as SEIU Healthcare, representing over 60,000 frontline HCWs, urged the Premier to focus on other major factors, such as low wages, to address an impending staffing crisis, with SEIU Healthcare president, Sharleen Stewart noting, in a joint statement with the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions, that “more (HCWs) are leaving the system because of poor wages and working conditions” rather than out of concern with insufficient vaccination among their co-workers (5).

Be that as it may, vaccine mandates for HCWs have since received broad support and have been enforced by most medical establishments, with many enforcing them to this day. They have also been supported by research addressing the perceived problem of “vaccine hesitancy” by, for instance, identifying HCWs’ personal characteristics—psychological, cultural, ideological—that may explain their less than full embrace of vaccination (7-11), and subsequently recommending interventions such as “targeted messaging” (10), better information or education (12) or, as a “last resort”, mandatory vaccination (9). This line of research has also framed those who doubt or resist the policy as uneducated or misinformed (7,12), and in all cases troublesome, especially given their role as trusted sources of vaccine information (8). As a result, there has been limited research on the vaccination experiences or perspectives on mandates of HCWs themselves, free from preconceptions about the desirability of vaccination (13). To address this gap, we surveyed HCWs in Ontario, Canada, documenting their experience of workplace vaccination mandates and their views about the impact of the policy on healthcare system sustainability and quality. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-24-79/rc).

Methods

We conducted an online survey of Ontario HCWs. Eligibility criteria included anyone working in a healthcare setting—whether in patient care, administrative, or maintenance services—in Ontario, and of any age and vaccination status. We advertised the study via the professional networks and contacts of the lead author. In turn, these contacts advertised it through social media. We also used a snowball sampling method whereby respondents were invited to disseminate recruitment materials among their own networks. Materials were resent at 7-day intervals over 1 month (14). Of the 918,700 people estimated to be employed in Ontario in healthcare and social assistance in 2021 (15), we recruited a convenience sample of 468 HCWs.

We pilot tested the survey with a sample of 5 HCWs and integrated their feedback prior to launching it in February 2024, collecting responses through March 2024. The survey consisted of 15 sections, with sections automatically skipped depending on vaccination status or job termination for non-compliance with mandatory vaccination. After informing respondents about the purpose of the research and the confidentiality of the data, confirming that they worked in Ontario, and obtaining informed consent, they were asked about their employment status and history, their experience of making vaccination decisions, the impact of the policy on their finances, personal and social relations, and mental and physical health, and their perspectives on the impact of the policy on patient care. The survey consisted of 88 questions, including multiple choice, short answer, and Likert scale (i.e., rank ordered responses). Sections included: demographics (8 questions); employment (5 questions); COVID-19 experiences (2 questions); informed consent (11 questions); vaccination decision making (3 questions); vaccine side effects (3 questions); accommodations (3 questions); personal impact of vaccination policies (9 questions); self-rated health changes (4 questions); vaccination requirements and employment status (2 questions); impacts of job termination (10 questions); impacts on patient care (23 questions); experiences of administering COVID-19 vaccines (4 questions); and an open ended question for further comments (1 optional question). Following the survey, respondents were entered into a raffle for a $100 gift card.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the York University Office of Research Ethics (No. 2023-389). Potential study participants were provided an information letter and consent form, including details on the study aims, methods, potential benefits and risks, and information about confidentiality and consent. They were informed of their right to withdraw consent at any time without consequences. The online survey questions were only accessible to participants after they had provided their freely informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Due to the exploratory nature of the research, we performed only a descriptive analysis of the data using Excel spreadsheets. The research team met regularly to review the data, discuss the analysis, and identify trends.

Results

Demographics

Most respondents (273/468, 58%) were between the ages of 35–44 years (138/468, 29.5%) and 45–54 years (135/468, 29%), followed by ages 55–64 years (105/468, 22.4%). Most respondents were women (385/468, 82.3%), living on a middle-income (286/468, 61.1%), were born in Canada (360/468, 77%), Caucasian/White (392/468, 84%), were married or living with a partner (338/468, 72.2%), and reported caretaking responsibilities for children or stepchildren (349/468, 74.5%) (264/468, 56.4%) (Table 1). The most commonly reported profession/area of occupation was nursing (125/468, 27%). About one-third of respondents (151/468, 32.3%) reported between 6 and 15 years of experience in their most recent career, close to one-third (136, 29.4%) between 16 and 25 years of experience, over one-fifth (100/468, 21.4%) over 26 years of experience, and a minority (63/468, 13.5%) 5 or fewer years. A large minority (218/468, 47%) reported 0–4 years of education/training, followed by close to one-third between 5–9 years (126/468, 27%), and over one-fifth (105/468, 22.4%) reporting 10 or more years of training. Most respondents (117/468, 25%) reported working in the Toronto health region, followed by the Southwest health region (121/468, 23%), and most were employed full time (147/468, 31.5%) (see Table 1 for further details).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 years | 0/468 | 0 |

| 25–34 years | 54/468 | 12 | |

| 35–44 years | 138/468 | 29.5 | |

| 45–54 years | 135/468 | 29 | |

| 55–64 years | 105/468 | 22.4 | |

| 65 or older | 15/468 | 3.2 | |

| Total respondents | 447/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 21/468 | 4.5 | |

| Gender | Woman | 385/468 | 82.3 |

| Man | 52/468 | 11.1 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Other (transgender woman; non-binary) | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Total respondents | 448/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 20/468 | 4.3 | |

| Socioeconomic status | Very low-income | 14/468 | 3 |

| Low-income | 64/468 | 14 | |

| Middle-income | 286/468 | 61.1 | |

| High middle-income | 59/468 | 13 | |

| High-income | 7/468 | 1.5 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 20/468 | 4.3 | |

| Total respondents | 450/468 | 96.2 | |

| No response | 18/468 | 4 | |

| Country of birth | Canada | 360/468 | 77 |

| USA | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Poland | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Romania | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 68/468 | 15 | |

| Total respondents | 447/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 21/468 | 4.5 | |

| Ethnic or cultural background | Caucasian or White | 392/468 | 84 |

| Latin American | 14/468 | 3 | |

| Black | 14/468 | 3 | |

| Indigenous | 11/468 | 2.4 | |

| South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, etc.) | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Chinese | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 15/468 | 3.2 | |

| No response | 22/468 | 5 | |

| Domestic status | Married or living with a partner | 338/468 | 72.2 |

| Single | 82/468 | 18 | |

| Widow(er) | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Other | 18/468 | 4 | |

| Total respondents | 447/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 21/468 | 4.5 | |

| Caretaking responsibilities | Children/stepchildren | 264/468 | 56.4 |

| Parents | 85/468 | 18.2 | |

| None | 139/468 | 30 | |

| Other | 19/468 | 4.1 | |

| No response | 18/367 | 4 | |

| Education level | Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) | 111/468 | 24 |

| Registered Nurse (RN) or Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) or Registered Practical Nurse (RPN) diploma | 73/468 | 16 | |

| Nursing Assistant Diploma | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Master of Science in Nursing (MScN) or Master of Nursing (MN) | 13/468 | 3 | |

| Nurse Practitioner (NP) graduate diploma | 4/468 | 1 | |

| Doctor of Medicine (MD) | 12/468 | 3 | |

| Paramedical or Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) program | 10/468 | 2.1 | |

| Bachelor of Science in Midwifery | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Bachelor of Health Science in Midwifery | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Master of Science in Midwifery | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Other Midwifery degree | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Bachelor of Health Sciences (BHSc) | 12/468 | 3 | |

| Master of Health Sciences (MHSc) | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Master of Public Health (MPH) | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| PhD (any field) | 7/468 | 1.5 | |

| Bachelor of Health Science in Occupational Therapy | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Master of Science in Occupational Therapy (MScOT) | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Master of Health Sciences (MHSc) | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy (BScPT) | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Master of Science in Physical Therapy (MScPT) | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Bachelor or advanced degree, Health Administration/Systems Management (e.g., BHAD) | 6/468 | 1.3 | |

| Bachelor or Doctor of Pharmacy | 3/468 | 1 | |

| Registered Pharmacy Technician (RPhT) | 7/468 | 1.5 | |

| Bachelor of Science in Nutrition or Food Sciences/Dietetics | 3/468 | 1 | |

| Medical Radiation Technologist Diploma | 8/468 | 2 | |

| Doctor of Dental Medicine/Surgery (DDM, DDS) | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Dental hygiene diploma | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Doctor of Optometry (OD) | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) diploma | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Acupuncture diploma | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Phytotherapy (herbal medicine) diploma | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Homeopathy | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 138/468 | 29.5 | |

| No response | 20/468 | 4.3 | |

| Profession/area of occupation | Registered nurse/registered psychiatric nurse | 125/468 | 27 |

| Licensed practical nurse | 40/468 | 9 | |

| Nurse aide/orderly/patient services associate (e.g., health care aide, long-term care aide, nursing assistant) | 28/468 | 6 | |

| Nursing coordinator/supervisor | 11/468 | 2.4 | |

| Personal support worker (PSW) | 12/468 | 3 | |

| Social worker | 7/468 | 1.5 | |

| Academic appointment/university affiliation | 12/468 | 3 | |

| In clinical practice | 74/468 | 16 | |

| Not in clinical practice | 24/468 | 5.1 | |

| Health profession student | 4/468 | 1 | |

| Health professional in training (e.g., resident) | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Specialist physician | 8/468 | 2 | |

| General practitioner/family physician | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Allied primary health practitioner (e.g., nurse practitioner, midwife, physician assistant) | 10/468 | 2.1 | |

| Paramedical occupation (e.g., EMT, ambulance attendant, advanced care paramedic) | 11/468 | 2.3 | |

| Physiotherapist or Physiotherapy Assistant (PTA) | 4/468 | 1 | |

| Occupational therapist or occupational therapy assistant (OTA) | 12/468 | 3 | |

| Medical technologist/technician (e.g., medical laboratory technologist, respiratory therapist) | 32/468 | 7 | |

| Dentist | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Dental care—technical occupation (e.g., dental hygienist, denturist) | 3/468 | 1 | |

| Dental assistant | 1/468 | 0.2 | |

| Optometrist | 2/468 | 0.4 | |

| Pharmacist or registered pharmacy technician | 9/468 | 2 | |

| Dietician/nutritionist | 5/468 | 1.1 | |

| Natural healing practitioner (e.g., acupuncturist, TCM practitioner) | 7/468 | 1.5 | |

| Other | 96/468 | 21 | |

| No response | 20/468 | 4.3 | |

| Years of experience in most recent career | 0–5 years | 63/468 | 13.5 |

| 6–10 years | 73/468 | 16 | |

| 11–15 years | 78/468 | 17 | |

| 16–20 years | 72/468 | 15.4 | |

| 21–25 years | 64/468 | 14 | |

| 26–30 years | 27/468 | 6 | |

| 31–35 years | 44/468 | 9.4 | |

| 36–39 years | 18/468 | 4 | |

| 40+ years | 11/468 | 2.4 | |

| Total respondents | 450/468 | 96.1 | |

| No response | 18/468 | 4 | |

| Years of education/training | 0–4 years | 218/468 | 47 |

| 5–9 years | 126/468 | 27 | |

| 10+ years | 105/468 | 22.4 | |

| Total respondents | 449/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 19/468 | 4.1 | |

| Ontario health region affiliation‡ | Northern region | 40/468 | 9 |

| Eastern region | 85/468 | 18.2 | |

| Southwest region | 121/468 | 23 | |

| Central region | 76/468 | 16.2 | |

| Toronto region | 117/468 | 25 | |

| Other | 13/468 | 3 | |

| No response | 22/468 | 5 | |

| Employment status | Employed full-time | 147/468 | 31.5 |

| Employed part-time | 97/468 | 21 | |

| Unemployed | 70/468 | 15 | |

| Self-employed | 70/468 | 15 | |

| Casual | 16/468 | 3.4 | |

| Contractor | 11/468 | 2.4 | |

| Other | 37/468 | 8 | |

| Total respondents | 448/468 | 96 | |

| No response | 20/468 | 4.3 |

†, some answers allow for multiple options, so totals do not always amount to 100%. ‡, construction forecasts. (no date). Definitions of Ontario regions. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from https://www.constructionforecasts.ca/en/reference/definitions-ontario-regions#:~:text=The%20Southwest%20region%20includes%20the,Stratford%2C%20Goderich%20and%20Owen%20Sound.

Vaccination decision and experiences

Most respondents (362/468, 77.4%) were not vaccinated (Figure 1). Of those who were vaccinated, most had completed a primary vaccine series (63/87, 72.4%), very few a partial primary series (13/87, 15%), and even fewer had been boosted once (5/63, 8%) or twice or more times (6/63, 9.5%). Most (65/87, 75%) were vaccinated primarily because it was mandated for work, a minority (14/87, 11%) to protect others, whether loved ones (6/87, 7%) or the larger community (4/87, 5%), and a smaller minority (4/87, 5%) to travel. Most vaccinated respondents (68/87, 78%) reported experiencing adverse effects post vaccination (16). Adverse effects were mild after the 1st dose (17/87, 20%), the 2nd dose (17/87, 20%), or the 3rd or more doses (3/87, 3.4%); moderate after 1st dose (20/87, 23%), the 2nd dose (8/87, 9.2%), or the 3rd or more doses (3/87, 3.4%), or serious after the 1st dose (8/87,9.2%), the 2nd (15/87, 17.2%), and the 3rd or more doses (3/87, 3.4%). Close to one-third of vaccinated respondents (29/87, 33.3%) did not communicate their reaction to a doctor, while over one-third (31/87, 35.6%) did. Among these, in only a minority of cases (5/31, 16%) a report was filed, in most cases no report was filed (17/31, 55%), and in close to one-third of cases (9/31, 29%) respondents did not know if a report had been filed. Nearly one-third (27/87, 31%) of vaccinated respondents reported that after experiencing an adverse reaction their employer had still required additional doses. Only about one-fifth (19/87, 22%) reported no adverse events post vaccination ever (Table 2).

Table 2

| Question | Options | N (total N=87) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary reason for getting vaccinated | To protect myself from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) | 1 | 1.1 |

| To protect my loved ones from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) | 6 | 7 | |

| To protect the larger community from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) | 4 | 5 | |

| It was mandated at work | 65 | 75 | |

| It was mandated at school/university | 1 | 1.1 | |

| It was mandated at social venues (e.g., restaurants) | 0 | 0 | |

| It was mandated for travel (e.g., visiting family or vacations) | 4 | 5 | |

| It was mandated to visit vulnerable loved ones (e.g., grandparent in nursing home) | 1 | 1.1 | |

| It was mandated at places of worship (e.g., church, temple, mosque) | 0 | 0 | |

| I did it to avoid rejection from friends/family members/members of the community | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 3 | 3.4 | |

| Total respondents | 86 | 99 | |

| No response | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Vaccine side effects (if vaccinated) | N/A (no reactions ever) | 19 | 22 |

| Mild reaction after 1st dose | 17 | 20 | |

| Mild reaction after 2nd dose | 17 | 20 | |

| Mild reaction after 3rd or later dose | 3 | 3.4 | |

| Moderate reaction after 1st dose | 20 | 23 | |

| Moderate reaction after 2nd dose | 8 | 9.2 | |

| Moderate reaction after 3rd or later dose | 3 | 3.4 | |

| Severe reaction after 1st dose | 8 | 9.2 | |

| Severe reaction after 2nd dose | 15 | 17.2 | |

| Severe reaction after 3rd or later dose | 3 | 3.4 | |

| Life-threatening after 1st dose | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Life-threatening after 2nd dose | 0 | 0 | |

| Life-threatening after 3rd dose or later dose | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 5 | 6 | |

| No response | 0 | 82 | |

| Communicated adverse reactions to GP/family doctor or other medical personnel | N/A (no adverse reaction) | 20 | 23 |

| No, I did not communicate my reaction to GP/other medical personnel | 29 | 33.3 | |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP/other medical personnel, and they filed a report | 5 | 6 | |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP/other medical personnel, but they did not file a report | 17 | 20 | |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP/other medical personnel, and I do not know if they filed a report | 9 | 10.3 | |

| Other | 6 | 7 | |

| Total respondents | 86 | 99 | |

| No response | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Experienced an adverse reaction after COVID-19 vaccine and still required to take additional doses | Yes | 27 | 31 |

| No | 48 | 55.2 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 11 | 13 | |

| Total respondents | 86 | 99 | |

| No response | 1 | 1.1 |

†, some answers allow for multiple options, so totals do not always amount to 100%. GP, general practitioner; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Personal and family impact of vaccination policies

Most respondents (311/468, 66.5%) agreed (50/468, 11%) or strongly agreed (261/468, 56%) that their current income was lower than it was prior to the introduction of vaccination mandates. Not surprisingly, most laid off respondents (302/361, 84%) also agreed (47/361, 13%) or strongly agreed (257/361, 71.2%) that being terminated had significantly reduced their income. Responses to the impact of vaccination policies on physical health were more mixed. About half (224/468, 48%) of respondents chose “not applicable”—unsurprisingly since the majority of respondents were unvaccinated. A minority (78/468, 17%), however, reported that they agreed (24/468, 5.1%) or strongly agreed (56/468, 12%) that their physical health had worsened after mandates were implemented, while the remainder (144/468, 31%) were neutral (30/468, 6.4%), disagreed (60/468, 13%) or strongly disagreed (54/468, 12%) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Statement | Strongly disagree, n [%] | Disagree, n [%] | Neutral, n [%] | Agree, n [%] | Strongly agree, n [%] | Not applicable, n [%] | No response, n [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My income is less than it was prior to the introduction of vaccination policies/mandates (N=468) | 34 [7.3] | 55 [12] | 28 [6] | 50 [11] | 261 [56] | 20 [4.3] | 20 [4.3] |

| Losing my job significantly reduced my income (N=361) | 12 [3.3] | 7 [2] | 15 [4.2] | 47 [13] | 257 [71.2] | 23 [6.4] | 0 |

| I have suffered chronic physical ailments due to employer vaccination requirements (N=468) | 54 [12] | 60 [13] | 30 [6.4] | 24 [5.1] | 56 [12] | 224 [48] | 20 [4.3] |

| I have suffered physical disability due to employer vaccination requirements (N=468) | 67 [14.3] | 68 [15] | 37 [8] | 14 [3] | 27 [6] | 234 [50] | 21 [4.5] |

| I have suffered anxiety and/or depression due to employer vaccination requirements (N=468) | 21 [4.5] | 15 [3.2] | 24 [5.1] | 85 [18.2] | 264 [56.4] | 38 [8.1] | 21 [4.5] |

| I have experienced suicidal thoughts due to employer vaccination requirements (N=468) | 158 [34] | 62 [13.2] | 55 [12] | 25 [5.3] | 60 [13] | 88 [19] | 20 [4.3] |

| I have sought help from a counsellor due to situations arising from vaccination requirements (N=468) | 74 [16] | 81 [17.3] | 48 [10.3] | 53 [11.3] | 124 [26.5] | 78 [17] | 20 [4.3] |

| My personal relationships (spouses, friends) suffered due to situations arising from vaccination requirements (N=468) | 28 [6] | 28 [6] | 32 [7] | 85 [18.2] | 255 [54.5] | 19 [4] | 21 [4.5] |

| I feel I have been unfairly treated by my employer regarding vaccination requirements (N=468) | 21 [4.5] | 6 [1.3] | 9 [2] | 15 [3.2] | 383 [82] | 14 [3] | 20 [4.3] |

| Losing my job had a negative impact on my physical health (N=361) | 15 [4.2] | 45 [12.5] | 60 [17] | 88 [24.4] | 131 [36.3] | 22 [6.1] | 0 |

| Losing my job had a negative impact on my mental health (N=361) | 10 [3] | 17 [5] | 14 [4] | 97 [27] | 202 [56] | 21 [6] | 0 |

Similarly, answers to whether respondents had suffered physical disabilities due to employer vaccination requirements were also mixed, with close to one-third (135/468, 29%) disagreeing (68/468, 15%) or strongly disagreeing (67/468, 14.3%) that they had, about one-tenth (41/468, 9%) agreeing (14/468, 3%) or strongly agreeing (27/468, 6%), and a slightly smaller proportion (37/468, 8%) remaining neutral. In contrast, among respondents who reported that they had been terminated due to their vaccination decisions, most (219/361, 61%) either agreed (88/361, 24.4%) or strongly agreed (131/361, 36.3%) that losing their job had had a negative impact on their physical health. Even more pronounced was the impact of job termination on respondents’ mental health, with most (299/361, 83%) agreeing (97/361, 27%) or strongly agreeing (202/361, 56%) that being terminated had had a negative impact (Table 3).

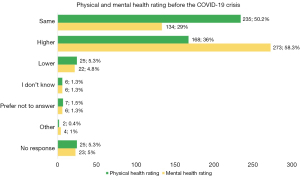

Further, most respondents (349/468, 75%) reported experiencing anxiety or depression due to employer vaccination mandates, with close to one-fifth (85/468, 18.2%) agreeing (25/468, 5.3%) or strongly agreeing (60/468, 13%) that they had experienced suicidal thoughts due to employer vaccination requirements, and over one-third (177/468, 38%) agreeing (53/468, 11.3%) or strongly agreeing (124/468, 26.5%) that they had sought help from a counsellor due to situations arising from these requirements. As well, most respondents (340/468, 73%) agreed (85/468, 18.2%) or strongly agreed (255/468, 54.5%) that their personal relationships had suffered due to situations arising from mandated vaccination, and most (398/468, 85%) agreed (15/468, 3.2%) or strongly agreed (383/468, 82%) with the statement “I feel I have been unfairly treated by my employer regarding vaccination requirements” (Table 3). Finally, while most respondents (280/468, 60%) reported good (127/468, 27.1%) or very good (153/468, 33%) physical health, over one-third (168/468, 36%) reported experiencing better physical health before COVID-19. This change was even more marked for mental health, that most (251/468, 54%) respondents rated as good (140/468, 30%) or very good (111/468, 24%), yet most (273/468, 58.3%) also rated their mental health as having been better before COVID-19 (Figures 2,3).

Workplace and labour market impact of vaccination policies

Nearly three-quarters (339/468, 72.4%) of respondents reported that they had been terminated due to their decision of not to be vaccinated, either not at all or after one or two doses (i.e., booster mandates). In addition, about one-fifth (103/468, 22%) reported that they had been subjected to disciplinary measures other than termination, such as accusations of professional misconduct, reports to licensing colleges, temporary suspension of pay, exclusion from pension plans, or withdrawal of their professional license (Table 4). Finally, most respondents (351/468, 75%) agreed (80/468, 17.1%) or strongly agreed (271/468, 58%) that they had experienced conflict among colleagues, and between employees and management after the introduction of vaccines or vaccination policies. As well, most respondents (383/468, 82%) reported knowing of HCWs who had taken early retirement due to COVID-19 policies, most (397/468, 85%) knew of colleagues who had been laid off due to non-compliance with vaccine mandates, and most (385/468, 82.3%) knew of colleagues who had resigned because they did not wish to take the vaccine (Table 5).

Table 4

| Question | Options | N (total N=468) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminated or laid off due to the decision to not receive the COVID-19 vaccine (first or subsequent doses)? | Yes | 339 | 72.4 |

| No | 88 | 19 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 22 | 5 | |

| Total respondents | 449 | 96 | |

| No response | 19 | 4.1 | |

| Subject to disciplinary measures other than layoffs (e.g., accusations of “professional misconduct”; reports to licensing colleges; temporary suspension of pay; exclusion from pension plan; withdrawal of professional license) | Yes | 103 | 22 |

| No | 274 | 56 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 23 | 5 | |

| Other | 49 | 10.5 | |

| No response | 19 | 4.1 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 5

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | Not applicable | No response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I experienced conflict among colleagues at work after the introduction of vaccines and/or vaccination policies | 22/468 (5%) | 27/468 (6%) | 21/468 (4.5%) | 78/468 (17%) | 271/468 (58%) | 28/468 (6%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I experienced conflict between employees and management at work after the introduction of vaccines and/or vaccination policies | 21/468 (4.5%) | 22/468 (5%) | 25/268 (5.3%) | 80/460 (17.1%) | 270/468 (58%) | 29/468 (6.2%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I know of health workers who have taken early retirement due to COVID-19 policies | 22/468 (5%) | 5/468 (1.1%) | 14/468 (3%) | 58/468 (12.4%) | 325/468 (69.4%) | 24/468 (5.1%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I know of health workers who have been laid off due to failure to comply with vaccination | 19/468 (4.1%) | 8/468 (2%) | 10/468 (2.1%) | 33/468 (7.1%) | 364/468 (78%) | 14/468 (3%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I know of health workers who have resigned because they did not wish to take the vaccine | 21/468 (4.5%) | 9/468 (2%) | 13/468 (3%) | 43/468 (9.2%) | 342/468 (73.1%) | 20/468 (4.3%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I know of students in the health professions who were deregistered due to non-compliance with vaccination policies | 36/468 (9%) | 36/468 (8%) | 41/468 (9%) | 23/468 (5%) | 206/468 (44%) | 106/468 (23%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I would return to my previous role if possible/if mandates were dropped | 93/361 (26%) | 41/361 (11.4%) | 59/361 (16.3%) | 35/361 (10%) | 108/361 (30%) | 25/361 (7%) | 0/361 (0%) |

| I intend to leave my occupation/the healthcare sector/industry due to my experiences with the COVID-19 policy | 44/468 (9.4%) | 60/468 (13%) | 88/468 (19%) | 58/468 (12.4%) | 141/468 (30.1%) | 56/468 (12%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

In addition, about half (229/468, 49%) of respondents knew of students in the health professions who were de-enrolled by their educational institutions due to non-compliance with vaccination policies. The response to the statement “I would return to my previous role if possible/if mandates were dropped” was split. While a large minority (143/361, 40%) agreed (35/361, 10%) or strongly agreed (108/361, 30%) that they would, about the same proportion (134/361, 37.1%) disagreed (41/361, 11.4%) or strongly disagreed (93/361, 26%), while a small minority (59/361, 16.3%) was neutral. Finally, respondents reported mixed feelings about remaining employed in healthcare: nearly half (199/468, 42.5%) agreed (58/468, 12.4%) or strongly agreed (141/468, 30.1%) that they intended to leave their occupation or the healthcare sector altogether due to their experiences with COVID-19 policies, while nearly a quarter (104/468, 22.2%) reported no plans to leave the industry, and about one-fifth (88/468, 19%) were neutral (Table 5).

Accommodation, equity considerations & informed consent

Most respondents (398/468, 85%) reported that they were not offered any alternatives to vaccination. Nearly half (218/468, 47%) requested, but did not receive, an exemption. The most common reason for requesting an exemption was religious (139/468, 30%), followed by conscientious objection (108/468, 23.1%) and medical (106/468, 23%) grounds. However, over one-fourth of respondents (121/468, 26%) reported that they did not request an exemption because they were not eligible or felt intimidated or discouraged by the rejection of co-workers’ requests. When asked if their employer (or professional college or public health authority if self-employed) had provided them with written information about COVID-19 vaccines, most respondents (274/468, 59%) reported that they had not, almost one-third (137/468, 29.3%) reported that they were provided information from public health agencies or equivalent, and very few (11/468, 2.4%) reported being provided a package insert from the vaccine manufacturer. Over one-third (160/468, 34.2%) reported that, if received, the information from employers had not enabled them to make an informed decision about vaccination (Table 6).

Table 6

| Question | Options | N (total N=468) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employer or regulatory authorities offered alternatives to vaccination | Yes, testing on site paid for by employer | 35 | 7.5 |

| Yes, test off site at your cost | 8 | 2 | |

| Yes, remote work | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Yes, educational training | 3 | 1 | |

| Yes, proof of natural immunity | 1 | 0.2 | |

| No, they did not offer any alternatives to vaccination | 398 | 85 | |

| Total respondents | 450 | 96 | |

| No response | 18 | 4 | |

| Requested exemption from vaccination | N/A (e.g., my employer did not request mandatory vaccination and I did not need an exemption) | 15 | 3.2 |

| No, I was not interested in requesting an exemption | 45 | 10 | |

| Yes, and I received an exemption | 10 | 2.1 | |

| Yes, but I did not receive an exemption | 218 | 47 | |

| No, I did not request an exemption (e.g., did not meet permissible criteria; discouraged that others were rejected; intimidated) | 121 | 26 | |

| Other | 42 | 9 | |

| No response | 19 | 4.1 | |

| Category of exemption | N/A (did not apply for exemption) | 191 | 41 |

| Medical | 106 | 23 | |

| Religious | 139 | 30 | |

| Conscientious | 108 | 23.1 | |

| Other | 26 | 6 | |

| No response | 20 | 4.3 | |

| Employer (or professional college or public health authority if self-employed) provided written information about the vaccines | Yes, I was provided a package insert from the vaccine manufacturer(s) | 11 | 2.4 |

| Yes, I was provided information from public health agencies or equivalent | 137 | 29.3 | |

| No, they never provided me with written information about the vaccines | 274 | 59 | |

| Other | 47 | 10 | |

| No response | 23 | 5 | |

| If you received written information from your employer (or professional college or public health authority if self-employed) did it enable you to make an informed decision about vaccination? | Yes | 46 | 10 |

| No | 160 | 34.2 | |

| I did not receive written information | 217 | 46.4 | |

| Other | 23 | 5 | |

| Total respondents | 446 | 95.3 | |

| No response | 21 | 4.5 |

When asked their level of agreement with a variety of statements related to informed consent, most respondents (417/468, 89.1%) disagreed (28/468, 6%) or strongly disagreed (389/468, 83.1%) that they had felt “entirely free to choose whether or not to get vaccinated”. In contrast, most (414/468, 88.5%) agreed (23/468, 5%) or strongly agreed (391/468, 84%) that they had safety concerns with COVID-19 vaccines, and more than half (260/468, 55.6%) agreed (28/468, 6%) or strongly agreed (212/468, 45.3%) that they had medical concerns, while close to half (226/468, 48.3%) agreed (35/468,7.5%) or strongly agreed (191/468, 41%) that they had religious concerns regarding the COVID-19 vaccines. Most respondents (354/468, 76%) also disagreed (58/468, 12.4%) or strongly disagreed (296/468, 63.2%) that they felt comfortable sharing their concerns with their employer, and most (400/468, 85.5%) agreed (56/468, 12%) or strongly agreed (344/468, 74%) that they did their own research regarding the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines. As well, most vaccinated respondents (56/87, 64.4%) agreed (5/87, 6%) or strongly agreed (51/87, 59%) that they had felt coerced to get vaccinated, and conversely, most (74/87, 85.1%) disagreed (3/87, 3.4%) or strongly disagreed (71/87, 82%) that they were happy with their choice to get vaccinated. In contrast, most unvaccinated respondents (335/362, 93%) agreed (9/362, 2.5%) or strongly agreed (326/362, 90.1%) that they were happy to have remained unvaccinated (Table 7).

Table 7

| Level of agreement with the following related to the decision on COVID-19 vaccines | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | NA | No response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I felt entirely free to choose whether or not to get vaccinated | 389/468 (83.1%) | 28/468 (6%) | 8/468 (2%) | 5/468 (1.1%) | 17/468 (3.6%) | 1/468 (0.2%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I felt coerced to get vaccinated (if not vaccinated, choose NA) | 21/87 (24.1%) | 4/87 (5%) | 6/87 (7%) | 5/87 (6%) | 51/87 (59%)† | 272/362 (75.1%) | 18/468 (4%) |

| I had safety concerns with the COVID-19 vaccines | 26/468 (6%) | 6/468 (1.3%) | 1/468 (0%) | 23/468 (5%) | 391/468 (84%) | 0/468 (0%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I had personal medical concerns with the COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., I have an autoimmune disorder) | 40/468 (9%) | 29/468 (6.2%) | 44/468 (9.2%) | 28/468 (6%) | 212/468 (45.4%) | 96/468 (21%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| I had religious concerns with the COVID-19 vaccines | 64/468 (14%) | 32/468 (7%) | 52/468 (11%) | 35/468 (7.5%) | 191/468 (41%) | 75/468 (16.1%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| I am happy with my choice to get vaccinated (if you did not get vaccinated choose NA) | 71/87 (82%) | 3/87 (3.4%) | 7/87 (8%) | 0/87 (0%) | 14/87 (16.1%) | 353/362 (98%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I am happy with my choice to NOT get vaccinated (if you got vaccinated choose NA) | 19/362 (5.2%) | 0/362 | 8/362 (2.2%) | 9/362 (2.5%) | 326/362 (90.1%) | 86/87 (99%) | 20/468 (4.1%) |

| I felt comfortable expressing safety concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines with my employer | 296/468 (63.2%) | 58/468 (12.4%) | 14/468 (3%) | 18/468 (4%) | 50/468 (11%) | 13/468 (3%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| I did my own research to determine the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines | 16/468 (3.4%) | 9/468 (2%) | 19/468 (4%) | 56/468 (12%) | 344/468 (74%) | 5/468 (1.1%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

†, estimated value using the sum of category ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘agree’ subtracted from the total number of vaccinated participants. NA, not applicable; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

HCWs views and experiences of mandates on patient care

Most respondents (351/468, 75%) had worked with COVID-19 positive or suspected patients prior to the vaccine mandate (Table 8), and most (357/468, 76.3%) agreed (104/468, 22.2%) or strongly agreed (253/468, 54.1%) that they had observed concerning patient care or procedural changes upon the onset of COVID-19 (Table 9). Similarly, most (355/468, 76%) agreed (95/468, 20.3%) or strongly agreed (260/468, 56%) that they had observed disturbing patient care or procedural changes upon the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, most (328/468, 70.1%) agreed (69/468, 15%) or strongly agreed (259/468, 55.3%) that they had observed differential treatment of patients based on their vaccination status, and most (321/468, 69%) agreed (78/468, 17%) or strongly agreed (243/468, 52%) that they had observed an increase in patient harms associated with the COVID-19 vaccine. Significantly, only a very small minority (24/468, 5.1%) agreed (10/468, 2.1%) or strongly agreed (14/468, 3%) that they had felt free to express to their employer their concerns about potential vaccine harms in patients, only a very small minority (36/468, 8%) agreed (11/468, 2.4%) or strongly agreed (25/468, 5.3%) that when they had expressed these concerns they had been documented or acted upon by their employer, and only a small minority (17/468, 4%) agreed (5/468, 1.1%) or strongly agreed (12/468; 3%) that from the perspective of a potential patient, they felt confident that the healthcare system would provide adequate and quality care while respecting their personal preferences and values (Table 9).

Table 8

| Question | Options | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worked with COVID-19 positive or suspected patients’ pre-vaccine mandate | Yes | 351/468 | 75 |

| No | 51/468 | 11 | |

| Not sure | 45/468 | 10 | |

| Other | 3/468 | 1 | |

| Total respondents | 450/468 | 96.2 | |

| No response | 18/468 | 4 | |

| Encouraged to report adverse events post vaccination if observed | Yes | 21/468 | 4.5 |

| No | 423/468 | 90.4 | |

| Total respondents | 444/468 | 95 | |

| No response | 24/468 | 5.1 | |

| Trained to report adverse events post-vaccination if observed | Yes | 20/468 | 4.3 |

| No | 424/468 | 91 | |

| Total | 444/468 | 95 | |

| No response | 24/468 | 5.1 | |

| Administering COVID-19 vaccines part of job responsibilities | Yes | 31/468 | 7 |

| No | 412/468 | 88 | |

| Total respondents | 443/468 | 95 | |

| No response | 25/468 | 5.3 | |

| Personally administered COVID-19 vaccines | Yes | 16/468 | 3.4 |

| No | 429/468 | 92 | |

| Total respondents | 445/468 | 95.1 | |

| No response | 23/468 | 5 | |

| Received compensation for administering COVID-19 vaccines | Yes | 8/16 | 50 |

| No | 8/16 | 50 | |

| Total respondents | 16/16 | 100 | |

| No response | 0/16 | 0 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 9

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | Not applicable | No response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I observed concerning patient care or procedural changes coinciding with the onset of the COVID-19 crises | 10/468 (2.1%) | 12/468 (3%) | 35/468 (7.5%) | 104/468 (22.2%) | 253/468 (54.1%) | 33/468 (7.1%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I observed concerning patient care changes after the introduction of the COVID-19 vaccines | 7/468 (1.5%) | 12/468 (3%) | 27/468 (6%) | 95/468 (20.3%) | 260/468 (56%) | 44/468 (9.4%) | 23/468 (5%) |

| I observed differential treatment of patients based on their vaccine status | 10/468 (2.1%) | 14/468 (3%) | 42/468 (9%) | 69/468 (15%) | 259/468 (55.3%) | 53/468 (11.3%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I observed an increase in patient harms associated with the COVID-19 vaccines | 7/468 (1.5%) | 14/468 (3%) | 49/468 (10.5%) | 78/468 (17%) | 243/468 (52%) | 57/468 (12.2%) | 20/468 (4.3%) |

| I felt free to express any concerns I had about patient care or potential vaccine harms with my employer | 313/468 (67%) | 52/468 (11.1%) | 15/468 (3.2%) | 10/468 (2.1%) | 14/468 (3%) | 45/468 (10%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| If I expressed concerns about patient care or potential vaccine harms, these concerns were documented and acted upon by my employer | 211/468 (45.1%) | 37/468 (8%) | 52/468 (11/1%) | 11/468 (2.4%) | 25/468 (5.3%) | 111/468 (24%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| From the perspective of a potential patient, I am confident that the current healthcare system will provide adequate and quality care while respecting my personal preferences and values | 342/468 (73.1%) | 58/468 (12.4%) | 24/468 (5.1%) | 5/468 (1.1%) | 12/468 (3%) | 8/468 (2%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| I was accused of undermining COVID-19 public health response/patient care due to my views/decisions about vaccination | 24/468 (5.1%) | 35/468 (7.5%) | 53/468 (11.3%) | 81/468 (17.3%) | 220/468 (47%) | 36/468 (8%) | 19/468 (4.1%) |

| I was disciplined for undermining COVID-19 public health response/patient care due to my views/decisions about vaccination | 43/468 (9.2%) | 54/468 (12%) | 48/468 (10.3%) | 43/468 (9.2%) | 181/468 (39%) | 78/468 (17%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I was coerced into recommending/administering COVID-19 vaccines against my best clinical judgment (e.g., patient may experience an adverse event, or has experienced an adverse event post vaccination, COVID-19 or other; patient too young/old to benefit from vaccination, patient experienced COVID-19 and likely has strong natural immunity) | 44/468 (9.4%) | 39/468 (8.3%) | 43/468 (9.2%) | 32/468 (7%) | 102/468 (22%) | 187/468 (40%) | 21/468 (4.5%) |

| I am aware that COVID-19 vaccines can cause serious or life-threatening injuries, including death | 0/16 | 0/16 | 1/16 (6.3%) | 3/16 (19%) | 12/16 (75%) | 0/16 | 0/16 |

| I felt coerced to administer COVID-19 vaccines at any point during the vaccination campaign | 1/16 (6.3%) | 0/16 | 1/16 (6.3%) | 3/16 (19%) | 12/16 (75%) | 0/16 | 0/16 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

As well, most (423/468, 90.1%) responded “no” when asked if they had been encouraged to report adverse events post vaccination if observed in patients. Nearly all (424/468, 91%) also reported “no” when asked if they had been trained to report adverse events post vaccination if observed (Table 8). Significantly, close to one-third of respondents (134/468, 29%) agreed (32/468, 7%) or strongly agreed (102/468, 22%) that they had felt coerced to recommend/administer vaccines against their best clinical judgment. As well, most respondents (301/468, 64.3%) agreed (81/468, 17.3%) or strongly agreed (220/468, 47%) that they had been accused of undermining COVID-19 public health response/patient care due to their reservations about vaccination, and close to half (224/468, 4%) agreed (43/468, 9.2%) or strongly agreed (181/468, 39%) that they were disciplined for this reason (Table 9). Finally, for a small number of respondents (16/468, 3.4%), job responsibilities included administering vaccines, and half of them (8/16, 50%) reported being reimbursed for the task (Table 8). Further, among the small number of respondents who had administered COVID-19 vaccines, most (15/16, 94%) agreed (3/16, 18.7%) or strongly agreed (12/16, 75%) that they believed that these can cause serious or life-threatening injuries, including death, and most (13/16, 81.3%) agreed (1/16, 6.2%) or strongly agreed (12/16, 75%) that they had felt coerced to administer COVID-19 vaccine despite their reservations (Table 9).

Discussion

In our survey of 468 HCWs in the province of Ontario, Canada, most of them had 16 or more years of professional experience, were unvaccinated or had not met full vaccination requirements, and had been terminated due to non-compliance with mandates. As well, and regardless of vaccination status, most respondents reported safety concerns with vaccination, yet did not request an exemption due to their experience of high rejection rates by employers. However, most unvaccinated workers reported satisfaction with their vaccination choices, although they also reported significant, negative impacts of workplace mandates on their finances, their mental health, their social and personal relationships, and to a lesser degree, their physical health. In contrast, within the minority of vaccinated respondents, most reported being dissatisfied with their vaccination decisions, as well as having experienced mild to serious post vaccine adverse events, with about one-quarter within this group reporting having been coerced into taking further doses, under threat of termination, despite these events.

In relation to patient care, a large minority of respondents reported having witnessed underreporting or dismissal by hospital management of adverse events post vaccination among patients, worse treatment of unvaccinated patients, and concerning changes in practice protocols. Most respondents also reported being accused of undermining patient care due to their reservations about vaccination, and close to half reported being disciplined for this reason. Most respondents within the very small number of those who actually administered COVID-19 vaccines reported that they had been coerced into doing so against their best clinical judgment. Finally, close to half of respondents reported their intention to leave the healthcare industry altogether.

This study has limitations. First, we relied on a convenience rather than random sample of HCW. Even when we advertised the study through a variety of channels, and invited HCWs of any vaccination status to participate, we recruited predominantly unvaccinated HCWs. Considering that an estimated 85% of HCWs in the province were vaccinated in October 2021, immediately before vaccine mandates were introduced (17)—and likely a higher percentage since, given that termination was penalty for non-compliance—our findings are therefore not representative or generalizable. That being said, it is worth noting that the minority of vaccinated respondents reported vaccine safety concerns and being vaccinated only because of the introduction of mandatory vaccination policies, with most of them feeling coerced into accepting vaccination. Therefore, the high rate of vaccination in the province may not necessarily indicate support for vaccination but rather inability to afford to be terminated. As well, most respondents were middle-income, women, and nursing professionals, only a handful were medical doctors, very few were low-paying—personal support workers, aides, or orderly—and only a small proportion self-identified as very low or very high income. It is likely that the policies impacted HCWs with different occupations and levels of income differentially, these sample characteristics further limiting the generalisability of our study. Our study is also cross-sectional, and we have only performed descriptive statistical analyses, so we are unable to observe the evolution of patterns across time, or relationships between variables, such as income and vaccination status. Very likely, there are income-level differences in HCWs’ ability to afford the consequences—primarily termination—of not complying with the policy, that our survey was unable to capture. There is, however, research suggesting that this may be the case. For example, a study of NHS elderly care home staff in England indicated that vaccine mandates led to lower rates of unvaccinated HCWs, especially among lower income workers (18)—unsurprisingly given that refusal was punished with job loss, which likely low paying HCWs are the least able to afford. That being said, better samples or more sophisticated methodological approaches would still be limited in their ability to address important legal and ethical challenges. More on this point shortly.

There exists, to be sure, ample research on the perceived problem of “suboptimal” vaccine uptake or of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs, in Canada and elsewhere. As has been noted, most of this research, implicitly or explicitly, overwhelmingly endorses full and continuing vaccination for HCWs, if necessary, through mandates (19). And there is little doubt that the policy of mandated vaccination has succeeded in increasing vaccination rates among HCWs (9,20,21)—unsurprisingly given the severe penalties imposed for non-compliance—although researchers have noted that when boosters have been recommended rather than mandated, uptake among HCWs has typically been very low, and have therefore recommended the “official abandonment” of the policy (22). However, if the goal is to provide safer and better quality of care, rather that increasing vaccination rates for their own sake, then the success of the policy of mandated vaccination is at best questionable. For example, the study mentioned earlier, of NHS elderly care home staff in England, indicated a reduction not only in rates of unvaccinated HCWs but also of between 3% and 4% in the healthcare labour force, equivalent to 14,000 to 19,000 fewer HCWs, that had a negative impact on the health and well-being of residents in these establishments, thus undermining the ostensible goal of the policy (18). As discussed by some of the respondents, the firing of HCWs during a health crisis which demanded significant healthcare resources appears to undermine the message from health and government officials that there was a serious health emergency. Further, if the goal of the policy had truly been to provide safer and better quality of care, policymakers should have given due consideration to the well-established superiority of naturally acquired versus artificial (i.e., vaccine) immunity (23), and would have aimed to recruit, instead of laying off, the HCWs in the province who acquired such immunity working tirelessly in 2020, when vaccines did not exist.

Beyond pragmatic considerations—impact on staff shortages, which type of immunity is superior, and so on—the policy of mandated vaccination for HCWs has important implications for law and ethics. Take the Canadian Constitution as an example. Back in 1996, the Canadian National Report on Immunization outlined a lack of precedence for mandatory vaccination, noting that in contrast to other countries, “immunization is not mandatory in Canada; it cannot be made mandatory because of the Canadian Constitution” (24). However, this provision of the report has been all but ignored in discussions around COVID-19 vaccination mandates. So apparently has been other important Canadian legislation, for instance, the 1996 Health Care Consent Act, which states that medical treatments should not be administered without the voluntary consent of individual recipients (25), and the 2004 Personal Health Information Protection Act, which states that consent for disclosure of personal information cannot be obtained through coercion (26).

Nevertheless, in recent years at least some courts have sided in favour of terminated HCWs in Ontario. One arbitrator, for instance, noted that the respondent, a medical establishment, had failed to consider evidence for the inability of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent transmission, and to grant accommodations for unvaccinated employees. One of the grounds for the arbitrator’s decisions was that hospital management, given mounting evidence for waning vaccine effectiveness, had decided against a booster mandate because the alleged benefits of boosters did not outweigh the risk of further staff losses. However, noted the arbitrator, current policy had still permitted the hospital to retain employees with only two vaccine doses, despite management’s acknowledgment of their waning effectiveness, while unvaccinated workers were terminated. An additional ground for siding in favour of terminated HCWs was that one of the plaintiffs had been fired after returning from parental leave in April 2023, long after evidence of waning effectiveness was available, and admitted by hospital managers themselves. Also referenced in the legal proceedings were hospital statistics recording that most COVID-19 infections had occurred among fully vaccinated staff, thus the conclusion of the arbitrator that the policy was “unreasonable” (27).

In another case pertaining to two HCWs in clerical positions, the arbitrator also sided with the HCWs upon concluding that, in their refusing to reveal their vaccination status, they were “exercising their right to choose whether to receive medical treatment and (…) whether to disclose private medical information” (…), that even a “reasonable vaccination policy (…) does not eliminate the grievors’ right of medical consent”, (and that) the mere fact that the (HCWs) were unwilling to have a vaccine injected into their bodies cannot fairly be characterized as an act of insubordination, or some other culpable conduct”, and, for this reason, termination was “not a permissible employer response to the exercise of this right” (28).

Similar legal issues have been debated in other countries, specifically on the matter of the weak or non-existent liability of vaccine manufacturers generally. For example, Holland has described models for vaccine injury liability in the USA and the European Union, detailing how, due to existing legislation and judicial decisions, vaccine makers in the USA have “almost blanket liability protection from damages for vaccine harms”, in contrast to the European Union, where, based on a ruling from the European Court of Justice (ECJ), someone injured by a vaccine has the right to compensation via a civil court, even if “a scientific consensus that a vaccine can cause the alleged injury does not yet exist” (29). The author proposed that making vaccine manufacturers legally liable for potential harms caused by their products would “better balance the concerns of public health and individual rights”, and therefore strengthen both vaccine safety and confidence. The same could be said about Canada, where, since 2017, all vaccine manufacturers, including COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers, have been legally immune to charges against them stemming from any harm caused by their products (30).

Nevertheless, there is little doubts that these harms exist, and evidence for them continues to accumulate (31-35). Identified adverse events post vaccination, such as myopericarditis upon receiving mRNA vaccines (36,37) and lack of reproductive toxicity data, admitted even by national public health authorities (38), are especially relevant to young populations. More recently, one study of over 99 million participants indicated an observed vs. expected (OE) ratio for acute disseminated encephalomyelitis of 3.78, for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis of 3.23, and for Guillain-Barré syndrome of 2.49, and an excess risk of serious adverse events of special interest, including death, between 10.1 and 15.1 (39).

As well, a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), upon prefacing that the benefits of (all) vaccines are “well-established”, reported “convincing evidence” of a causal relationship between mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and myocarditis, “inadequate (evidence) to accept or reject a causal relationship between mRNA-1273 (Moderna) and ischemic stroke”, evidence for accepting “a causal relationship between Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccines” and two specific adverse effects, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome, and evidence for multiple vaccines and various shoulder injuries (40). Finally, a report from the World Council for Health based on data from several reporting systems—VigiAccess Database (WHO), the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (USA; CDC, FDA), Eudravigilance (European Medicines Agency), and the UK Yellow Card Scheme (NHS)—found an “unprecedented” number of reports of adverse events in all the included databases, along with evidence for waning, or lack of, effectiveness, concluding that COVID-19 vaccines should be recalled (41). Our research provides support for these scientific, legal, and ethical challenges.

Conclusions

In 2021 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) announced six evaluation criteria that jointly provide “a normative framework (…) to determine the merit or worth of an intervention”—a policy, a strategy, or an activity (42). The first criterion is “relevance”, i.e., to what extent a policy is responsive to beneficiaries, meaning those who “benefit directly or indirectly from the policy”. The second criterion is “coherence”, i.e., to what extent a policy is compatible with other policies in a given setting. The third is “effectiveness”, i.e., to what extent a policy has achieved or is expected to achieve its objectives”. The fourth criterion is “efficiency”, to what extent a policy converts inputs into outputs in the “most cost-effective way possible, as compared to feasible alternatives in the context” and within a reasonable timeframe. The fifth criterion is “impact”, i.e., to what extent a policy “has generated or is expected to generate significant positive or negative, intended or unintended”, effects. The sixth and last criterion is “sustainability”, i.e., whether benefits are likely to last (42).

If our findings indicate a trend in the health care sector in Ontario, Canada, they suggest that by these criteria the policy of mandated vaccination for HCWs in the province has failed in its purported goal of promoting safer healthcare environments and achieving better care. Concerning “relevance”, the intended beneficiaries, whether HCWs, patients, or communities at large, have been harmed by exacerbated staff shortages, intimidating work environments, and health professionals coerced into acting against their best clinical judgment. Concerning “coherence”, the policy has proven to be at odds with other policies within health settings, such as the imperative to maintain adequate staffing levels or to respect informed consent and bodily autonomy, not only for HCWs but for those patients who, for whatever reason, decline vaccination. As to “effectiveness”, there is no evidence that the policy has improved patient care—as suggested by our findings, it has likely worsened it.

Concerning “efficiency”, there is no evidence that the policy has been more cost-effective than comparable alternatives, such as relying on the superiority of naturally acquired immunity over artificial immunity (23,43-45), acquired by most HCWs during 2020 as they treated patients in critical need, and for this reason were celebrated as heroes by the media and the authorities (46,47). Notably, naturally acquired immunity, achieved through recovery from a prior infection, was not recognized by healthcare employers in Canada. In fact, there is no evidence that such (then unvaccinated) workers were deemed a threat to patient safety and disciplined for that reason. Concerning “impact”, our findings also suggest that the overall impact of the policy on the well-being of HCWs and the sustainability of health systems has also been negative. Finally, concerning “sustainability”, with close to half of our sample of highly trained and experienced HCWs intending to leave the health professions, we see no evidence for any net benefits, either current or future. We conclude that if, by the OECD criteria, the policy of mandated vaccination for HCWs has failed, this failure, along with the contested efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines, their negative impact on HCWs’ wellbeing, staffing levels, and patient care, and the threat that mandates represent to longstanding bioethical principles such as informed consent and bodily autonomy (48,49), negates any basis—policy, scientific, or ethical—to continue with the practice.

Acknowledgments

C.C. thanks the many professional and lay organizations, students, trainees, and friends who have afforded spaces of reflection and debate over the past years, and especially her husband Julian Field, for his editorial feedback and support. N.H. thanks her family and friends for their encouragement and support, and Dr. Chaufan for her mentorship. R.M. thanks her friends, family, and Dr. Chaufan for their support and guidance. All authors are grateful to the participants for sharing with us their life experiences for making this study possible.

Funding: This work was funded by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-24-79/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-24-79/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-24-79/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-24-79/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the York University Office of Research Ethics (No. 2023-389). Potential study participants were provided an information letter and consent form, including details on the study aims, methods, potential benefits and risks, and information about confidentiality and consent. They were informed of their right to withdraw consent at any time without consequences. The online survey questions were only accessible to participants after they had provided their freely informed consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Fitzpatrick T, Allin S, Camillo CA, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Rollout: Ontario. CoVaRR-Net and North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; COVID-19 Vaccination Rollout Monitor; 2022.

- Ismail SJ, Zhao L, Tunis MC, et al. Key populations for early COVID-19 immunization: preliminary guidance for policy. CMAJ 2020;192:E1620-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Value-for-Money Audit: COVID-19 Vaccination Program. 2022. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en22/AR_COVIDVaccination_en22.pdf

- CBC News. Documents show northern Ontario hospital advised premier against vaccine mandate. CBC News. 2022 Feb 3 [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/hearst-hospital-vaccine-mandate-1.6337761

- McKenzie-Sutter H. Ontario Hospital Association recommends mandatory staff COVID shots in letter to Ford. The Canadian Press. 2021 Oct 20. Available online: https://nationalpost.com/pmn/news-pmn/canada-news-pmn/ontario-reports-304-covid-19-cases-four-deaths-on-wednesday

- Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. RNAO response to Premier Ford mandatory vaccination letter to hospital CEOs and health organizations. 2021 [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available online: https://rnao.ca/news/media-releases/rnao-response-to-premier-ford-mandatory-vaccination-letter-to-hospital-ceos-and

- Achat HM, Stubbs JM, Mittal R. Australian healthcare workers and COVID-19 vaccination: Is mandating now or for future variants necessary? Aust N Z J Public Health 2022;46:95-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evans CT, DeYoung BJ, Gray EL, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine intentions and uptake in a tertiary-care healthcare system: A longitudinal study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022;43:1806-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JT, Sean Hu S, Zhou T, et al. Employer requirements and COVID-19 vaccination and attitudes among healthcare personnel in the U.S.: Findings from National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module, August - September 2021. Vaccine 2022;40:7476-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oberleitner LMS, Lucia VC, Navin MC, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Concerns and Reasons for Acceptance Among US Health Care Personnel. Public Health Rep 2022;137:1227-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulrich AK, Pankratz GK, Bohn B, et al. COVID-19 vaccine confidence and reasons for vaccination among health care workers and household members. Vaccine 2022;40:5856-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dietrich LG, Lüthy A, Lucas Ramanathan P, et al. Healthcare professional and professional stakeholders' perspectives on vaccine mandates in Switzerland: A mixed-methods study. Vaccine 2022;40:7397-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaufan C, Hemsing N. Is resistance to Covid-19 vaccination a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry of vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. AIMS Public Health 2024;11:688-714. [Crossref]

- McDonald CI, Parry PI, Rhodes P. Economic and Psychosocial Impact of Covid-19 Vaccine Non-Compliance amongst Australian Healthcare Workers. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 2024;8:40-50. [Crossref]

- Government of Canada. Health Care and Social Assistance (NAICS 62): Ontario, 2023-2025. 2023. Available online: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/trend-analysis/job-market-reports/ontario/sectoral-profile-health-care

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) | Protocol Development | CTEP. 2021 [cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

- Jerome A. Ontario issues enhanced vaccine certificates, stresses need for health-care staff to get vaccinated. Law 360 Canada; 2021. Available online: https://www.law360.ca/ca/articles/1756254/ontario-issues-enhanced-vaccine-certificates-stresses-need-for-health-care-staff-to-get-vaccinated

- Girma S, Paton D. Covid-19 Vaccines As a Condition of Employment: Impact on Uptake, Staffing, and Mortality in Elderly Care Homes. Management Science 2023;70:2882-99. [Crossref]

- Chaufan C, Hemsing N. Is resistance to Covid-19 vaccination a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry of vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. AIMS Public Health 2024;11:688-714. [Crossref]

- Poyiadji N, Tassopoulos A, Myers DT, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates: Impact on Radiology Department Operations and Mitigation Strategies. J Am Coll Radiol 2022;19:437-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ritter AZ, Kelly J, Kent RM, et al. Implementation of a Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination Condition of Employment in a Community Nursing Home. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:1998-2002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walkowiak MP, Domaradzki J, Walkowiak D. Are We Facing a Tsunami of Vaccine Hesitancy or Outdated Pandemic Policy in Times of Omicron? Analyzing Changes of COVID-19 Vaccination Trends in Poland. Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11:1065. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gazit S, Shlezinger R, Perez G, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Naturally Acquired Immunity versus Vaccine-induced Immunity, Reinfections versus Breakthrough Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:e545-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Canadian National Report on Immunization, 1996. Ottawa, ON: Division of Immunization Bureau of Infectious Diseases Laboratory Centre for Disease Control Health Protection Branch, Health Canada; 1997 May. Report No.: Volume 23S4, pg. 3.

- Government of Ontario. Health Care Consent Act, 1996, S.O. 1996, c. 2, Sched. A. Jul 24, 2014. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view

- Government of Ontario. Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004, S.O. 2004, c. 3, Sched. A. Jul 24, 2014. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view

- Hayes J. Quinte Health v Ontario Nurses Association. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/k34gz

- Parmar J. Humber River Hospital v Teamsters Local Union No. 419. 2024, pg. 4. [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/k3d7g

- Holland MS. Liability for Vaccine Injury: The United States, the European Union, and the Developing World. Emory Law Journal 2018;67:415-7.

- Gilmore R. Coronavirus vaccine makers are shielded from liability. Here’s why officials say that’s normal - National | Globalnews.ca. Global News. 2020 Dec 14 [cited 2024 Jun 10]. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/7521148/coronavirus-vaccine-safety-liability-government-anand-pfizer/

- Buchan SA, Seo CY, Johnson C, et al. Epidemiology of Myocarditis and Pericarditis Following mRNA Vaccination by Vaccine Product, Schedule, and Interdose Interval Among Adolescents and Adults in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2218505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fraiman J, Erviti J, Jones M, et al. Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine 2022;40:5798-805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karlstad Ø, Hovi P, Husby A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis in a Nordic Cohort Study of 23 Million Residents. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:600-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li M, Yuan J, Lv G, et al. Myocarditis and Pericarditis following COVID-19 Vaccination: Inequalities in Age and Vaccine Types. J Pers Med 2021;11:1106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mansanguan S, Charunwatthana P, Piyaphanee W, et al. Cardiovascular Manifestation of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022;7:196. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naveed Z, Li J, Spencer M, et al. Observed versus expected rates of myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ 2022;194:E1529-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Statement from the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health (CCMOH): Update on COVID-19 Vaccines and the Risk of Myocarditis and Pericarditis. 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 16]. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2021/10/statement-from-the-council-of-chief-medical-officers-of-health-ccmoh-update-on-covid-19-vaccines-and-the-risk-of-myocarditis-and-pericarditis.html

- UK.Gov. GOV.UK/MHRA. 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Summary of the Public Assessment Report for COVID-19 Vaccine Pfizer/BioNTech. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-pfizer-biontech-vaccine-for-covid-19/summary-public-assessment-report-for-pfizerbiontech-covid-19-vaccine

- Faksova K, Walsh D, Jiang Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2024;42:2200-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Evidence Review of the Adverse Effects of COVID-19 Vaccination and Intramuscular Vaccine Administration. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2024:5 [cited 2024 Jun 9].

- World Council for Health. WCH Covid-19 Vaccine Pharmacovigilance Report. Bath: World Council for Health; 2022 Jun [cited 2024 Apr 17].

- OECD. Evaluation Criteria. 2021 [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm

- Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, et al. Waning of BNT162b2 Vaccine Protection against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med 2021;385:e83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chemaitelly H, Nagelkerke N, Ayoub HH, et al. Duration of immune protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection. J Travel Med 2022;29:taac109. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Charlett A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of antibody-positive compared with antibody-negative health-care workers in England: a large, multicentre, prospective cohort study (SIREN). Lancet 2021;397:1459-69. Erratum in: Lancet 2021;397:1710. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Office of the Premier. Ontario Supporting Frontline Heroes of COVID-19 with Pandemic Pay. news.ontario.ca. 2020 [cited 2024 Jun 11]. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56768/ontario-supporting-frontline-heroes-of-covid-19-with-pandemic-pay

- Simmons T. Front-line heroes: Meet the people fighting COVID-19 in Toronto and share your stories. CBC News. 2020 Mar 30 [cited 2024 Jun 10]. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/front-line-heroes-covid-19-1.5512485

- UNESCO. Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. 2005 [cited 2023 Mar 27]. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/ethics-science-technology/bioethics-and-human-rights

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. N Engl J Med 1964;271:473-4. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Chaufan C, Hemsing N, Moncrieffe R. COVID-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: a cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. J Public Health Emerg 2025;9:4.