The Mediterranean diet: an “evergreen” diet

The rising incidence of obesity in worldwide is associated with several serious medical complications, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes (T2D), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (1,2). This constellation is also recognized as the metabolic syndrome and is characterized by underlying insulin resistance (IR). In reality, the exact mechanism by which obesity promotes metabolic syndrome is not fully understood.

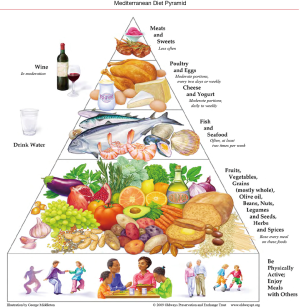

The Mediterranean diet is a modern nutritional recommendation originally inspired by the dietary patterns of Southern Italy, Spain, and Greece in the 1950s (3). The principal aspects of this diet include proportionally high consumption of olive oil, legumes, unrefined cereals, fruits, and vegetables, moderate to high consumption of fish, moderate consumption of dairy products (mostly as cheese and yogurt), moderate wine consumption, and low consumption of non-fish meat products (4) (Figure 1). The Mediterranean diet would have varied benefits on the health and therefore also on body weight and metabolic syndrome.

The PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) trial (5) has also provided first-level evidence of cardiovascular protection by the Mediterranean diet. Estruch et al. (6) showed that a long-term intervention with an unrestricted-calorie, high-vegetable-fat Mediterranean diet was associated with decreases in bodyweight and less gain in central adiposity compared with a control diet. Overall, Estruch et al. (6) showed that an increase in vegetable fat intake from natural sources in the setting of a Mediterranean diet had little effect on bodyweight or central adiposity in older individuals who were mostly overweight or obese at baseline. Instead, small but significant reductions in weight and lesser increases in waist circumference were seen in participants given the Mediterranean diet interventions compared with the control group, as reported by Estruch et al. (6). Torjesen showed that high fat Mediterranean diet is not linked to greater weight gain than low fat diet (7).

However, there is tentative evidence that the Mediterranean diet lowers the risk of heart disease and early death (8,9). In a Mediterranean trial focused on dietary fat interventions, baseline intake of saturated and animal fat was not associated with T2D incidence, but the yearly updated intake of saturated and animal fat was associated with a higher risk of T2D (10). Cheese and butter intake was associated with a higher risk of T2D, whereas whole-fat yogurt intake was associated with a lower risk of T2D (10).

Olive oil may be the main source of fat and health-promoting component of the Mediterranean diet (11). There is preliminary evidence that regular consumption of olive oil may lower all-cause mortality and the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and several chronic diseases (12).

Furthermore, a dietary intervention consisting of a Mediterranean diet could delay or slow down the natural progression of NAFLD, thus, being beneficial for its prevention and treatment, as showed by Cueto-Galán et al. (13).

The human gastrointestinal microbiota functions as an important mediator of diet for host metabolism. Thus, the intestinal microbiota might be selected on the basis of the diets that we consume, which can open opportunities to affect gut health through modulation of gut microbiota with dietary supplementations (14).

Recently, Hernáez et al. (15) showed that the traditional Mediterranean diet, especially when enriched with virgin olive oil, improved HDL atheroprotective functions in humans.

A simplified way of eating healthily by excluding highly-processed foods, is presumed to be the Paleolithic diet (a diet based on vegetables, fruits, nuts, roots, meat, organ meats) which improves IR, ameliorates dyslipidemia, reduces hypertension and may reduce the risk of age-related diseases (16). Whalen et al. (17) suggest that diets closer to Paleolithic or Mediterranean diet patterns may be inversely associated with all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Following a Mediterranean diet has many benefits, but there are still a lot of misconceptions on exactly how to take advantage of the lifestyle to lead a healthier, longer life. There is an apparent importance of healthier lifestyle habits including physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet also among children and adolescents, as reported by Martino et al. (18).

Our knowledge of the pathological consequences of lack of adequate exercise on adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and the liver is improving, and this will help establish more specific guidelines for the proper exercise regimens that will improve underlying metabolic pathways (19). Environmental factors that discourage physical activity include an environment that encourages automobile use rather than walking (like lack of sidewalks), and that has few cues to promote activity and numerous cues that discourage activity (television, computers, etc.) (19).

Either way, in 2013, UNESCO added the Mediterranean diet to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of Italy (promoter), Morocco, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, and Croatia (20). It was chosen because “The Mediterranean diet involves a set of skills, knowledge, rituals, symbols and traditions concerning crops, harvesting, fishing, animal husbandry, conservation, processing, cooking, and particularly the sharing and consumption of food.” (20).

Our feeling is that the Mediterranean diet remains an “evergreen”, is the appropriate word, diet.

Acknowledgments

Editor-in-Chief Baoli Zhu (Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing, China).

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Public Health and Emergency. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.05.02). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Finelli C, Tarantino G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diet and gut microbiota. EXCLI J 2014;13:461-90. [PubMed]

- Finelli C, Tarantino G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:802-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keys A. Mediterranean diet and public health: personal reflections. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;61:1321S-3S. [PubMed]

- Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, et al. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a literature review. Nutrients 2015;7:9139-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1279-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, et al. Effect of a high-fat Mediterranean diet on bodyweight and waist circumference: a prespecified secondary outcomes analysis of the PREDIMED randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:666-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torjesen I. High fat Mediterranean diet is not linked to greater weight gain than low fat diet. BMJ 2016;353:i3171. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tong TY, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, et al. Prospective association of the Mediterranean diet with cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality and its population impact in a non-Mediterranean population: the EPIC-Norfolk study. BMC Med 2016;14:135. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amor AJ, Serra-Mir M, Martínez-González MA, et al. Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease by the Framingham-REGICOR Equation in the High-Risk PREDIMED Cohort: Impact of the Mediterranean Diet Across Different Risk Strata. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré M, Becerra-Tomás N, Ruiz-Canela M, et al. Total and subtypes of dietary fat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:723-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piroddi M, Albini A, Fabiani R, et al. Nutrigenomics of extra-virgin olive oil: A review. Biofactors 2017;43:17-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parkinson L, Cicerale S. The Health Benefiting Mechanisms of Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds. Molecules 2016;21: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cueto-Galán R, Barón FJ, Valdivielso P, et al. Changes in fatty liver index after consuming a Mediterranean diet: 6-year follow-up of the PREDIMED-Malaga trial. Med Clin (Barc) 2017. [Epub ahead of print].

- Shankar V, Gouda M, Moncivaiz J, et al. Differences in Gut Metabolites and Microbial Composition and Functions between Egyptian and U.S. Children Are Consistent with Their Diets. mSystems 2017;2(1).

- Hernáez Á, Castañer O, Elosua R, et al. Mediterranean Diet improves High-Density lipoprotein function in High-Cardiovascular-Risk individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2017;135:633-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarantino G, Citro V, Finelli C. Hype or reality: should patients with metabolic syndrome-related NAFLD be on the Hunter-Gatherer (paleo) Diet to decrease morbidity? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2015;24:359-68. [PubMed]

- Whalen KA, Judd S, McCullough ML, et al. Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diet Pattern Scores Are Inversely Associated with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in Adults. J Nutr 2017;147:612-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martino F, Puddu PE, Lamacchia F, et al. Mediterranean diet and physical activity impact on metabolic syndrome among children and adolescents from Southern Italy: Contribution from the Calabrian Sierras Community Study (CSCS) Int J Cardiol 2016;225:284-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finelli C, Tarantino G. Have guidelines addressing physical activity been established in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:6790-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mediterranean diet - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884

Cite this article as: Finelli C. The Mediterranean diet: an “evergreen” diet. J Public Health Emerg 2017;1:54.