Save A Life (SALI) model: an intervention model to achieve development goals through public NGO partnership (PNP), capability development and evidence-based practice

Introduction

Definitions of NGOs and CBOs

Non-governmental organization (NGO) and community-based organization (CBO) are both considered as important third parties that are non-governmental, non-private service providers. The difference between them is that NGOs are generally formally structured and registered with the government authorities and are formally constituted to provide a benefit to the general public or the world at large through the provision of advocacy or services. While, CBO are usually unofficial community groups based in the community in which it serves (1).

World Bank uses the term ‘civil society organization’ (CSO) for both types. World Bank has defined CSO as “non-governmental and not-for-profit organizations that have a presence in public life, expressing the interests and values of their members or others, based on ethical, cultural, political, scientific, religious or philanthropic considerations. CSOs therefore refer to a wide array of organizations: community groups, non-governmental organizations, labor unions, indigenous groups, charitable organizations, faith-based organizations, professional associations, and foundations” (2). In this paper we use both terms NGOs and CSOs interchangeably.

According to the Sudan Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), the Sudanese Voluntary and Humanitarian Work Act of 2006 (VHWA) recognizes two different national organizational forms: (I) a “charitable organization” which is defined as an “organization that may be established by citizens, groups or individuals and having the financial ability to establish and sustain charitable activities”; (II) a “civil society organization” is “a civil society organization that practices voluntary and humanitarian work for not-for-profit purposes and which is registered in accordance with the provisions of the Act”. It further defines foreign voluntary organizations as non-governmental, or semi-governmental organizations, having international, or regional capacity, which is registered under the provisions of the Act, or licensed to work in Sudan, in accordance with the country’s agreement (3).

The most fragile countries face urgent humanitarian crises as well as decades of post-conflict reconstruction. There is an undeniable humanitarian imperative to recognize and address the urgent needs of communities affected by disaster and conflict—yet humanitarian aid that only provides immediate relief generally does not provide communities with sustainable and resilient health systems.

Over the past two decades, the number of civil society actors at local, national and global levels has grown significantly, as has their influence in public life. Many scholars and policy-makers now see civil society as an important factor in consolidating and sustaining democracy, fostering pro-poor development policies, attracting investment funding through impact investing, achieving gender equality and fighting corruption (4).

Partnerships with CSOs are vital and critical in a world characterized by increasingly complex development challenges. These include rising conflict within and between states, expanding epidemics and rapid depletion of the natural resources (5). Therefore, mobilization of new investments is critical for achieving the 2030 Development Agenda, especially in low and middle-income countries.

The significant long-term negative impact of crises upon overall national development has resulted in poor health and extreme poverty being increasingly aggregated within fragile countries. In order for aid to have the greatest impact, fragile countries must also be provided with the guidance, support and capabilities they need to develop their own resilience.

The currently adopted service delivery models just focus on delivering short-term, quick fix, and unsustainable services and lack the long-term benefits to the communities. This is hindering NGOs development and stopping them from being in a leading position to deliver sustainable and systemic health care services.

Conceptual framework

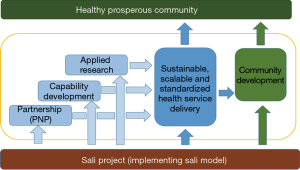

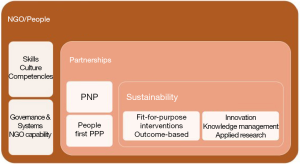

In this paper we used the “Taqaddum Framework”. The idea for SALI was initially conceived and put into practice by Professor Dr. Ibrahim A. Janahi, Dr. David Dombkins and a number of medical and technical expertise. Taqaddum is an accelerated capability development framework that has three components (refer Figure 1) that includes eight competences essential for NGOs to play their role as key actors in health and development. The 1st component is concerned with the “people and the NGO systems”. The main focus is on: organizational culture, staff competencies and skills, internal systems and governance. The 2nd component is “partnership”, in particular the public NGO partnership (PNP) model, how to implement it and how to produce effective sustainable outcomes. The 3rd component is “sustainability” and how to ensure it through evidence-based practice and encouragement of innovative interventions.

Role of NGOs in sustainable health projects and development

Effective partnerships

Government in developing countries cannot on their own fund or fulfill all the tasks required for the human development goals. This requires active participation of community-based organizations and societies (1). The role of NGOs and CSOs in achieving SDGs is really practical, reaching grass roots; hence it should not be just “hit and run”. Koffi Annan, UN Secretary General stated: “Civil society occupies a unique space where ideas are born, where mindsets are changed, and where the work of sustainable development doesn’t just get talked about, but gets done” (5).

The civil society role becomes larger when looking at the international NGOs (INGOs). It is now well recognized that INGOs have successfully advocated for major policy shifts in many areas, in addition to their great contribution in health, environment, human rights, and development (6).

Both the Millennium Development Goals (MSDGs) and SDGs have considered partnership as an important component to achieve their goals and targets. This partnership agreement is not just a donor-implementer relationship. It goes beyond that, including their contribution in advocacy, policy generation and socioeconomic developmental changes. This is what is called effective partnership which promotes effective development. The ‘Busan Partnership Agreement’ has defined the role of CSO in this effective development as: “promoting sustainable change that addresses the causes as well as the symptoms of poverty, inequality and marginalization, through the use of diverse and complementary instruments, policies and actors” (7).

SALI PNP: a new approach of partnership

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) is calling for a new PPP approach called “people first” approach that ensures wider sustainable participations of communities and effective partnerships. This approach considers NGOs as a fourth sector that provides many of the core services to poor and vulnerable people. Governments should focus on developing this sector through development of local NGOs into “For-Benefit Organizations” (FBO) that can attract funding from impact investing. Hence, countries will develop both capacity and capability in PPP that in turn will attract the private sector to support future PPP projects (8).

Dombkins [2017] proposed the implementation of new types of partnerships, such as the “inverted bid model” and “public NGO partnerships (PNP)” that do not require a high level of PPP readiness and that are designed to attract funding from equity investors and impact investing (1). The “Save A Life Model (SALI)” is based on this PNP approach in implementing sustainable health projects in developing countries. This model provides low-medium income countries (LMICs) with an innovative strategy to obtain the benefits from PPP projects. We do believe PNP is a viable option and superior to PPP because: (I) developing NGOs into FBO will ensure effective investment and return their profits to the community. (II) The United Nations is now re-focusing its PPP towards putting people first PPP and public-civil society partnerships. (III) Communities are much more trusting of CSOs than the private sector. (IV) For-benefit organizations could be equally competitive and entrepreneurial as the private sector. The model identifies eight key competencies: systemic approach, NGO accountability, training, education and best practice, contract management, performance measures, sustainability and ongoing review, risk and dispute mitigation, and innovation (2).

Partnering contribution in health

The provision of healthcare infrastructure and services is a massive obligation for both governments and the private sector. Some estimates place the cumulative expenditure on healthcare infrastructure over the last decade to be more than $3.6 trillion. Meanwhile, accessibility to basic healthcare services to most of the population in LMICs is still very limited. This challenge requires more efficient and effective use of resources and an increase in the overall capacity to achieve universal health care (UHC). Therefore, active contribution through effective partnerships with all related health actors is a must. Among these, CSOs have a very large task in LMICs in providing humanitarian short-term services as well as sustainable health services (8).

The provision of basic public utilities and services such as public health care, is a human right that is necessary to maintain human dignity. Public services are a key ‘dividend of peace’ that are increasingly incorporated directly into peace agreements—however, the maintenance (or resumption) of core public services has been an area in which fragile contexts and the global humanitarian system (including the UN) have to-date performed poorly. The engagement of INGOs and local NGOS with health policy and health is substantially dependent on the legal and political framework of each country. However, in general, they are often key players through their bottom-up approach (2).

Scott et al. and his colleagues had reported four core functions that partnering with NGOs can play—(I) “empowerment”: is a key benefit of civil society engagement. This is a fundamental principle in achieving SDGs and UHC. (II) “Service delivery”: this is perhaps the most common and the strength of CSOs. Variety of health services provided by CSOs range from well-run health care facilities to outreach to vulnerable populations, social campaigns, and volunteers. (III) “Flexibility”: the cost is very low in most cases. The bureaucracy and levels of decision making are usually short. (IV) “Participation in policy”: this is one of the key benefits. CSOs can bring new information to decision-makers, whether through research, through close contacts with particular populations, or through bringing opinions that are born neither in the state nor in the private sector (9).

It is well recognized that the common contributions of the CSOs are in humanitarian aid and interventions including health. This provides immediate relief that is not ‘sustainable’ in either a financial, social or environmental sense. It does address the immediate symptoms of vulnerable communities; however, it does not address the original underlying causes of vulnerability. These underlying causes can only be addressed through development projects, applied research, and knowledge management. This is where competent CSOs can contribute effectively (2).

At grass root level, CSOs are considered part of the social fabric of the community. Hence, effective local organizations can serve better because of their proximity, both physically and socially, to local people. They are locally rooted institutions that have vital expertise in the interpersonal and caring relationships in people’s everyday lives.

Capacity of NGOs

The term capacity refers to the ability of individuals, institutions and societies to do something. That means capacity exists at the individual level, at an institutional level, and at a societal level. Capacity building’s broad aim is to improve the internal governance of CSOs to ensure better financial sustainability, improve its ability in coordination, and producing quality services and outcomes. The Institute of Development Studies defines capacity as “the ability to undertake context analysis; navigate complexity; understand and engage with power; learn and adapt; undertake advocacy and influence change; make alliances; and generate a base of support” (10).

The role of capable NGOs in the new paradigm

The current global paradigm shift is talking about development effectiveness rather than just aid effectiveness. Recognizing the role of CSOs in this new paradigm, ‘Istanbul Principles’ has identified two requirements that need to be met: (I) enable CSOs to exercise their roles as independent development actors, with a particular focus on an enabling environment, consistent with agreed international rights, that maximizes the contributions of CSOs to development; (II) encourage CSOs to implement practices that strengthen their accountability and their contribution to development effectiveness (11).

In line with that, the Monterrey Consensus established commitments to increase the volume and quality of foreign aid to finance the SDGs. However, the evidence showed that the increased levels of aid did not yield expected results in development performance (7). The initial explanation could be that LMICs are generally lacking the skills and capacity to deliver sustainable projects using effective PPP and evidence-based approaches. In most cases they lack the basic legal framework, the personnel and technical capacity (8).

Despite the enormous contributions that civil society organizations have made to advancing the world’s understanding of sustainable development, communities are generally the least well-positioned to have a voice in international summits (5). The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs online platform for SDGs provides a space for sharing knowledge and expertise among different actors that are engaged in multi-stakeholder SDG-related partnerships and voluntary commitments. Active contribution in such activities, requires NGOs to have a degree of competencies in management and research skills (7).

Capacity vs. capability

In this paper we have talked about capability rather than capacity. And even in the SALI model capability is used instead of capacity. This is because capability is wider in meaning and goes beyond just capacity of staff and systems to involve what is to be done currently and strategically in a complex changing environment. Lanny Vincent has differentiated between these terms as “capacity refers to an amount or volume, is it enough, and how to grow. Capability refers to aptitude or a process that can be developed or improved, how to do it and are these the right skills currently and in the future”. The Fay Fuller Foundation provides an apt definition: “capacity and capability support is not a ‘one over the other’ proposition, both are critical. But in the search for impact, results and sustainability we urge philanthropists to think about the capability of the organization they are looking to support, and the role they may have in improving this” (12). Developing skills and knowledge is just one aspect of capability development. Being able to apply those skills in different contexts, with confidence, differentiates skill and capability. Hence, creating capability is about moving away from segmented activities of development to holistic activities that have more meaning and purpose.

Assessing NGOs capability

To assess, building capability and strengthening the role of CSOs is a global concern. Different approaches and methodologies have been exercised. Some of the approaches use existing secondary evidence, such as the CIVICUS Civil Society Index, while some are using a specific framework, such as the Istanbul Principles and the European Centre for Development Policy and Management’s Five Capacities Framework. Whatever framework or approach is used, it is important to focus on identifying the drivers and motivators that support capacity and sustainability using the endogenous energy and ownership (10). The SALI model is making use of the fruits of these practices and contextualize them in CSOs in LMIC and FCV regions. SALI is currently implementing the SALI capacity assessment tool as an entry gate to establish NGO-specific capability programs meeting required interventions.

Capability and fund attraction and absorption

Besides its efficient role on the ground, a capable NGO has greater potential to attract international global funding and ability to enter into effective partnerships. Failure to absorb the global funds allocated or disbursed for the developing countries is a persistent problem in many grants, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. At the end of 2016, among 34 countries in Africa, only about 65% of funds from signed grants over the previous three years had been disbursed. The fund absorption capacity of the recipients, whether governments or NGOs, is identified by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) as the main contributing factor (13).

Capacity of NGOs to contribute in Global Health Research and evidence generation

There is a need to more effectively include NGOs in all aspects of health research in order to maximize the potential benefits of research. NGOs, moreover, can and should play an instrumental role in coalitions for global health.

As stated earlier, NGOs are contributing at all stages of the services and hence are expected to share in all stages of the research cycle, fostering the relevance and effectiveness of the research, priority setting, assessing situations, and knowledge translation to action. They have a key role in resource mobilization for research, the generation, utilization and management of knowledge, and capacity development. Yet, typically, the involvement of NGOs in research is downstream from knowledge production and it usually takes the form of a partnership with universities or dedicated research agencies (14).

SALI model

Background

SALI is a model based on the PNP approach aiming at sustainable solutions/projects to save lives in fragile and conflict-affected countries. This model has been developed and piloted during the period 2016–2020. Three components drive the successful development and establishment of this model: (I) most of the members of the technical working group leading the establishment of this model have more than 25 years’ experience working in NGOs providing health and humanitarian activities. (II) The experience of the team is augmented by technical expertise provided by the Complex Program Group (CPG) (a global consultancy in Australia that has decades of experience in complex project management and PPP partnerships). (III) Participative approach in development of the model and wide sharing of the process involving different related actors including—locally: Ministry of Health, HAC, Health Insurance, WHO, UN agencies, and NGOs; and internationally the model was shared with the World Bank at the Fragile, Conflict and Violence (FCV) forum in Washington, DC, 2016 and at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) International Centre of Excellence PPP forum in Geneva, 2018. In both forums the model has been recognized and was introduced in the UNECE Report ‘Revised Guiding Principles on People-First Public-Private Partnerships for the United Nations Development Goals” (8).

Components of the model

The general goal of SALI model is to provide a structured capability development program that transforms local NGOs from being humanitarian aid-dependent, into development-oriented organizations that deliver sustainable core public services guided by evidence. Based on this goal, the three components of the model include: (I) effective partnerships (PNP); (II) capability development (including both systems and personnel); and (III) applied research and evidence generation. No ethical approval is needed for this study as no human samples were collected and this merely descriptive study for the progress of an organization.

Each component has a set of requirements, guidance and toolkits for implementation. According to the model (Figure 2) chronologically, the model is initiated by developing the capability of NGOs to establish effective partnerships and manage the business case, funding, design, implementation and operation of infrastructure and services delivery projects. These two steps ensure effective implementation and the applied research component leads to higher quality and performance of the projects. The outcome of interactions of these three components leads to sustainable, standardized, and scalable services that are guided by evidence and innovation. Over time and through wide involvement of NGOs the impact will be reflected in development and healthy prosperous communities.

1st component: establishing effective partnership (PNP):

SALI is adopting the People First PPP (PNP) approach. As discussed earlier, for LMICs such as Sudan, there are very limited opportunities to use PPP due to the very limited ability to access international financial PPP funding and the low level of PPP readiness in both the public and private sectors.

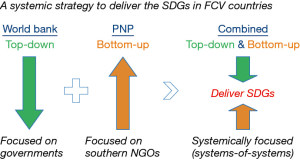

The World Bank has recognized that traditional top down approaches to PPP will not work in developing and fragile countries. There is a need to build innovative partnerships that bridge bottom-up and top-down approaches (5). The PNP model is bottom up and compliments the multi-lateral organizations top down approach (Figure 3).

Rationale of focusing on NGOs

Achieving the UN SDGs requires partnerships in all service delivery actors. In LMIC and FCV regions local NGOs are a fast-growing service provider. In addition, local NGOs are characterized by their rapid response capabilities, and the ability to access areas that may be difficult for the government. Despite that, NGOs are characterized by: weak internal systems and non-existence research culture and evidence guided practice.

The pilot started by developing capacities of SALI-partner NGOs on how to establish effective partnerships. These NGOs were selected based on specific criteria mainly: their legal status; experience in providing health and humanitarian services; and basic infrastructures. The first activity conducted was the partnering workshop including, in addition to SALI-partners NGOs, all stakeholders in the country (MOH, Health Insurance Fund, WHO, UNICEF, NGOs, HAC). Together they drafted SALI objectives in Sudan and signed the SALI charter. This is now considered as a blueprint for SALI in the country.

SALI partnering process

SALI toolkit provides a guide for the ‘Partnering Process’ which is defined as “a voluntary organized process by which multiple stakeholders having shared interests perform as a team to achieve mutually beneficial goals. It is based on establishing these goals early in the project lifecycle, building trusting relationships, and engaging in collaborative problem solving” (2). SALI is adopting the following partnering processes:

- Establishing an institutional capacity to manage PNP contracts and ensure sustained growth;

- Appropriate legal/regulatory framework with strong political support;

- Extensive feasibility studies, staged business case development, risk analysis, and Gateway reviews of proposed projects;

- Effective organizational structures rooted in transparency to streamline decision-making, issues management, emergence, and to ensure effective implementation;

- Deep understanding of each party’s agreement scope and effective contract compliance (time, cost, & quality) backed up with a professional, valid, and reliable contract management capability;

- Clear communication between government and different parties.

According to our experience in SALI, this component of the model is the most challenging one. To be an established system this requires at least 5–10 years. The ultimate goal is to enable the NGOs and the country to develop capabilities in PPP and to provide tangible proof to the international community that they can work successfully in PNP.

2nd component: capability development

SALI capability program focuses on southern NGOs delivering targeted humanitarian services for vulnerable communities, using a sustainable outsourcing framework that also supports the longer-term development of local health systems and resilient community behaviors.

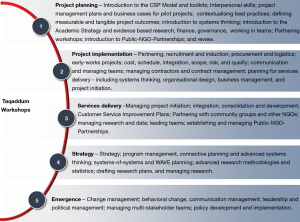

The structured capability development program is based upon fourteen validated toolkits. (refer Figure 4) The toolkits work together as a system to deliver accelerated capability development and are structured around four areas of operational relevance to local NGOs in fragile countries.

It is internationally recognized that traditional methodologies and competencies for strategic formulation, project management and services delivery are inadequate for dealing with real world complexity and emergence. The challenges facing fragile contexts are complex and emergent. Social, political, financial, environmental and political changes drive emergent outcomes that cannot be foreseen.

SALI Taqaddum modality

It is a new modality of training adopted during SALI pilot period to fast-track development of the NGOs implementing SALI pilot projects. This modality is based on a sandwich training educational method in which participants have an alternating training between direct teaching and indirect teaching modalities. During workshops the participants receive direct interactive lectures, group work, and seminars; and indirect teaching through applied hands-on and working on proposals and projects under mentoring.

SALI uses five staged workshops for capability development (Figure 5). The key principle is that sound foundational capabilities must be developed first, and upon which more advanced capabilities can subsequently be built.

Each of the workshops is four weeks in length, spread over 2 years in total. Each workshop focuses on just-in-time capability development, with progressively more advanced skills applied to real-time projects. Workshop outcomes are further reinforced through mentoring, monthly partnering meetings to assess team performance, and customer services improvement plans.

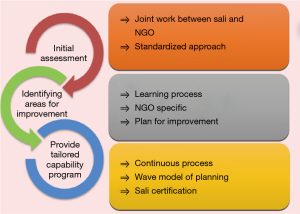

The structured capability development program is built on a three-tier approach (refer Figure 6). The process starts by assessing the NGO capabilities based upon best-practice and locally-contextualized standards. The purpose is to identify areas for improvement and to design tailored capability building program to enable the partner NGOs to function as highly competent international organizations. SALI assessment tool has eight themes: (I) leadership; (II) strategies and governance; (III) people and result; (IV) partnerships; (V) financial and procurement systems; (VI) processes and quality; (VII) customers and society results; (VIII) systems and performance. Each of these themes has an assigned weight, which is used to calculate the final assessment score (360 points).

The assessment will identify gaps and areas for improvement. The results will guide the capability program to provide required support in the following:

- Provides specific internal systems training packages focus on: project management, research methodology, finance and procurement, partnerships and systems, leadership and management, performance management, and quality tools.

- Supports NGO in developing feasibility analysis, project plans and business cases for humanitarian projects, and in making funding and finance submissions.

- Provides SALI’s applied project delivery capabilities focus on: partnerships, quality service delivery, and training of care providers, software, and integrated applied research.

- Supports NGO in integrating applied research with projects and programs through training in research competencies and strengthening research cultures.

3rd component: applied research

Applied research is of paramount importance for any organization seeking continuous improvement of its performance and looking for evidence-based solutions that are value-for-money and fit-for-purpose. In spite of this fact, research is considered a path less travelled by NGOs working in the health sector in conflict-affected and resource-limited settings. Postulated causes include lack of required competencies and absence of the culture and enabling environment for research.

Building the research capacity of NGOs working in the health sector in developing countries is one of the SALI core objectives. As mentioned in above sections, applied research represents one of the three pillars upon which the SALI model is designed. The ultimate goal of applied research in SALI model is to generate the evidence base for proper interventions and continuous improvement within the projects managed under SALI model.

The main objective of integrating applied research in projects implemented using SALI model is not just for providing evidence to guide implementation, but also to introduce the research culture as part of NGO systems and organizational culture. This enables NGOs to better contribute in health and policy development.

SALI is using an easy hands-on approach through providing technical support and training in basic skills in collection and analysis of data, conducting mini research, doing assessment, running proper audits and evaluation. In addition, supporting NGOs to represent their findings in a scientific way and how to communicate locally and internationally.

Case study of the first cohort

A team composed of about 50 individuals was selected from the staff of two NGOs working in projects implemented under supervision of SALI. A structured hands-on, field-based training that covered all phases of research was provided. An electronic mobile-phone based application was used for data collection with a central hub checking for data completeness and entry on a daily basis and providing instant required advice to the field collectors. The selected team was trained on how to conduct household health-related surveys using this e-data collection tool.

The team conducted two applied health system research projects. The two studies are titled: “The impact of Mobile clinics on the population health of rural areas” and “The impact of the SALI nutritional project on the nutritional status of children under-five years living in conflict-hit areas”. Besides the research culture strengthening, these studies have also addressed practical issues linked to their practice and the projects implemented, including: analysis of the gaps in the existing health system, identification of the major health problems and the risk components associated with them so that they can customize the range of service delivery to the most pressing needs of local communities, analysis of the health determinants, health-seeking behaviors and attitudes of local communities towards health issues.

Based on this pilot experience, we think that transforming NGOs practice to enrich the humanitarian library with evidence-based studies has a great potential. NGOs members are interested to learn and apply research competencies in their work.

SALI: way forward

SALI has a vision to be the premier model of excellence to be adopted by the NGOs in the region. This vision is doable, however, difficult and challenging. Two important components will determine the success of achieving a tangible impact; first, widening the base to get a large number of partners and implementing NGOs using the model’ and second, institutionalization of SALI capability program.

Step one: SALI to be recognized as a model of implementation. This requires further work on fine tuning the model and marketing locally and regionally.

Step two: SALI Organization itself to be a certified agent providing SALI-certificates to NGOs fulfilling the 360 points according to SALI certification assessment tool. It is our future goal, that SALI-certified NGO will be recognized and have increased potentiality and eligibility to attract international funding and PPP projects.

Step three: individuals and participants joining SALI capability program to see this program as part of their career development and personal promotion through: either certification of the training program as certified courses from accredited authorities or through institutionalization of SALI capability development curriculum as postgraduate degrees in higher education institutes.

Conclusions

Investing in the development of local NGOs is a critical lever to achieve the SDGs in fragile and conflict-affected countries. SALI model is a pragmatic model to transform the way humanitarian projects are delivered in terms of focus, governance, sustainability, funding, finance, and research, value for money, fit for purpose, and delivering systemic outcomes. The initial findings reflect a strong need to change the culture and mindset of the NGO communities to be led by development, sustainability and evidence-based practice. Local and international “of interest” of partners and stakeholders in SALI model paves the road for SALI to become a globally recognized model of intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the support of Qatar charities, the support of SALI staff and also support of the staff in Patients Helping Fund, Khartoum, Sudan. We are also grateful to Dr. David and Dr. Margaux Dombkins of the Complex Program Group for their ongoing support.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Mohamed H. Ahmed, Heitham Awadalla and Ahmed O. Almobarak) for the series “The Role of Sudanese Diaspora and NGO in Health System in Sudan” published in Journal of Public Health and Emergency. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2018.09.03). The series “The Role of Sudanese Diaspora and NGO in Health System in Sudan” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. HA serves as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. MHA serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Public Health and Emergency from Aug 2017 to Jul 2019 and served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- UNDP and Civil Society Organizations: A Policy of Engagement. United Nations Development Programme, New York, 2001.

- David Dombkins, 2017. Complex Program Group Fourth Sector Partnerships Toolkit Public NGO Partnerships (PNP) Toolkit to build Fourth Sector Organisations Effective Capability Development Process. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36521511/Complex_Program_Group_Fourth_Sector_Partnerships_Toolkit_Public_NGO_Partnerships_PNP_Toolkit_to_build_Fourth_Sector_Organisations_Effective_Capability_Development_Process

- ICNL, 2006. A Study of the Sudanese Voluntary and Humanitarian Work Act 2006. The International Center for Not-For-Profit Law. Available online: http://www.sudanconsortium.org/darfur_consortium_actions/reports/2015/humanitarian%20law%20studyf.pdf

- Volkhart Finn Heinrich, 2002. Assessing and Strengthening Civil Society Worldwide. A Project Description of the CIVICUS Civil Society Index: A Participatory Needs Assessment & Action-Planning Tool for Civil Society.

- UNDP, 2003. Partners-in-Human-Development-Report-UNDP-and-Civil-Society-Organizations_EN

- ONGO, 2006. NGO participation arrangements in other agencies of the UN System. Available online: https://www.itu.int/council/groups/stakeholders/Resources/Non-Paper%20on%20NGO%20Participation%20in%20the%20UN%20System3%20_CONGO_.pdf

- Atwood JB. 2012. Creating a Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation. Center for Global Development. Available online: www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/1426543

- UNECE, 2017. Revised Guiding Principles on People-first PPPs for the UN SDGs. Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/ceci/documents/2018/PPP/Forum/Documents/Revised_Guiding_Principles_for_People-first_PPPs_in_support_of_the_UN_SDGs-Part_I.pdf

- Greer SL, Wismar M, Pastorino G, et al. Civil society and health: Contributions and potential (2017). WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Institute of Development Studies, 2016. Strengthening the capacity of civil society Organisations to enhance democratization, decentralization and local governance processes Practice Paper. Available online: https://www.shareweb.ch/site/DDLGN/Documents/CSO%20CapacityPracticePaper_FINALAug2016%20(2).pdf

- Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, 211. Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/49650173.pdf

-

Fay Fuller Foundation 2016 . Available online: https://fayfullerfoundation.com.au/2016/02/capacity-building-versus-capability-building/ - Independent observer of Global Fun. Available online: http://www.aidspan.org/gfo_article/failure-absorb-global-fund-money-african-constituencies-sound-alarm

- Delisle H, Roberts JH, Munro M, et al. The role of NGOs in global health research for development. Health Res Policy Syst 2005;3:3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Awadalla H, Janahi IA, Dombkins D, Elnour FA, Abbass O, Omer AA, Nurain KM, Abdelwahab A, Algibali OY, Juma BE, Ahmed MH. Save A Life (SALI) model: an intervention model to achieve development goals through public NGO partnership (PNP), capability development and evidence-based practice. J Public Health Emerg 2018;2:24.