聚焦儿童外科手术:中、低等收入国家的儿童外科手术情况

介绍

如果没有将儿童外科手术完全纳入,全球儿童健康的概念就是不完整的。全球约17亿儿童没能得到安全、及时、可负担的外科手术和麻醉服务[1]。在全世界最不发达国家和低收入国家中,约40%的人口由15岁以下儿童组成,在尼日尔这一比例超过50%[2]。

根据《柳叶刀》全球外科委员会(LCoGS)具有里程碑意义的报告,LMICs还额外需要1.43亿外科手术以避免终身残疾和死亡[3]。然而,儿童外科手术的未达到手术需求(USN)的相关数据仍不完整。Smith等人报告在乌干达地区,国家的儿科USN率达到6.9%,USN的比例在5岁以下儿童中更高[4]。此外,Butler和同事们查看了4个低收入国家的USN,发现19%的儿童有外科手术需求,其中62%的儿童没有被满足[5]。或许我们并不吃惊,低收入国家的婴儿死亡率极高,达到50‰;在高收入国家,这一比例是5‰[2]。更令人担忧的是,新生儿疾病占残疾调整生命年(DALYs)的8%,先天性异常和围产期疾病占全世界外科DALYs的13%[6]。

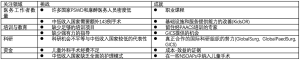

外科手术照顾在预防发病和病死事件中发挥重要作用,减少患者和家庭疾病支出,实现联合国可持续发展目标(SDGs)[1,7-9]。第三天SDG(SDG-3)旨在2030年以前,消除发生在新生儿及5岁以下儿童的可预防的死亡事件,将新生儿死亡率降低到12‰,将5岁以下儿童死亡率降低到25‰。有充分证据显示,在5岁以下儿童中,外伤引起的死亡多于艾滋病、疟疾和结核病导致的死亡的总和[11]。此外,鉴于在2018年死亡的620万儿童和青少年中,大多数死亡是由可预防的原因造成的,手术和麻醉护理在降低新生儿和儿童死亡率方面的关键作用不容忽视[10]。自2015年以来,几项进步——包括“LGoCS”“疾病控制优先事项”“第三版基本外科手术卷”“世界卫生大会第68.15号决议”,旨在积极倡导向所有人提供安全和负担得起的外科治疗,无论他们在哪里出生或居住[3,12]。不幸的是,全球对儿童手术的巨大需求仍然未被充分探索和研究。近年来,这一领域的发展势头不断增强,但仍有很多领域需要深入研究。因此,在这篇综述文章中,我们将讨论全球儿童外科的挑战和成就,重点是医务工作者数量、培训和教育、研究和经济(表1)。我们使用术语“global children’s surgery”而不是“global pediatric surgery”,以涵盖所有满足儿童需求的外科分支。

Full table

医务工作者数量

世界各地儿童外科医生的需求和供应仍然存在巨大的差距。有趣的是,在一项关于儿科外科手术医务工作者数量和培训需求的全球比较中,Lalchandani和Dunn指出,每百万儿童的儿科外科医生数量与一个国家的出生率成反比,加纳的出生率最高,但儿科外科工作人员密度最低[13]。然而,在人均国内生产总值(GDP)低于2万美元的国家,儿科外科医生的数量与人均国内生产总值(GDP)呈正相关[13]。在他们调查的15个高、中低收入国家中,每百万儿童的儿科医生数量从0.51到29.30不等[13]。许多非洲和南亚国家似乎比其他国家更受这些严重差距的影响[14]。例如,马拉维每百万儿童中只有0.17名儿童外科医生[15];同样,巴基斯坦的儿童外科医生密度为每百万儿童0.4人[16]。这些数据再次表明,生活在世界上一些最贫穷和资源最有限地区的儿童对外科护理的需求最高,但提供相应服务的医务工作者数量却是最低的。除了减轻USN的负担,提供外科护理也与结果有关。Hamad等人使用一种新的方法定义了关键的PSWD,以改善全球的手术结果。他们报告称,在他们的病例系列中,80%或以上的生存率与15岁以下儿童中至少有4名儿科医生的PSWD显著相关(OR 16.8, P<0.0001, 95% CI: 5.66~49.88)[17]。儿童外科是一个复杂的领域,有多个分支专业,需要专门的培训和深入的解剖学、生理学、药理学和病理学知识。重要的是要认识到,儿童不仅仅是“小大人”,他们有独特的围手术期护理需求。基于这些认知,对儿童外科工作人员的检查表明,除了外科医生外,儿童麻醉和护理工作人员也严重短缺[18-21]。Dubowitz和他的同事报告说,中低收入国家麻醉提供者的人均比例通常比高收入国家低100倍[22]。此外,世界卫生组织的全球外科数据库表明,在全球约55万名麻醉师中,仅12%在非洲和东南亚执业,而这两个地区的人口占世界人口的三分之一[23]。因此,专门照顾儿童,特别是新生儿的麻醉师就更少了。

许多因素导致了中低收入国家医务工作者数量不足的现状。特别是缺乏足够的培训项目、专家移民到其他国家、国家内部资源分配不公平、以及相关外科护理提供者和其他利益攸关方积极性的丧失等原因[24,25]。在涉及撒哈拉以南六个非洲国家的一项调查中,Burch等人指出,更好的经费支持和教育机会、获得最新的技术和设备以及改善的生活和工作环境是促使医学生在非洲以外继续接受培训的重要原因[26]。

职业培训与教育

强有力的培训项目和教育机会的可获得性与专业儿童外科护理提供者的可获得性相关联,这反过来又使儿童获得外科和麻醉护理的可获得性得到改善。Ozgediz及其同事在对乌干达进行的案例研究中提到,大多数紧急外科护理是由医务人员和麻醉人员在一级医院提供的,他们没有接受外科或麻醉专科住院医师培训或实习培训[27]。世界上很多资源有限的国家和地区没有足够数量的医学院和儿科手术实习或项目培训计划[3]。此外,学校和项目大多位于在城市地区,这增加了农村儿童接受护理的难度,也增加了学员和手术提供人员以最佳方式接触各种疾病以学习其临床特征和管理方法的难度[24]。缺乏培训机会并不是唯一的挑战。最近,医科学生和毕业生对外科手术的兴趣也有所下降[28-30]。影响选择儿科或儿童外科作为职业选择的因素的数据仍然有限。在一项来自沙特阿拉伯的单一国家调查中,Alshahrani和他的同事注意到,在300多名医科学生和实习生中,没有一位受访者将儿科外科作为他们的专业选择[31]。进一步研究以更好地理解专业选择和影响世界不同地区医学生做出决定的因素是必要的,但可以肯定的是,强大的导师的可及性是影响学生或实习生追求外科职业生涯的显著因素。在这种情况下,越来越多的证据强调了导师在外科医生一生中的重要性[32-34]。接受导师指导的个体更早实现目标,职业满意度更高[33]。鉴于世界范围内,尤其是在低收入和中等收入国家,儿科外科医生的密度很低,许多学生和受训人员在考虑从事儿童外科手术时可能会感到沮丧或迷失,或可能决定在国外接受专科培训[26]。这些因素可以解释为什么根据2009年的一项调查,巴西168个儿科手术点中有98个没有被使用[35]。在另一项研究中,Chirdan等人指出,24.4%的非洲儿科医生在非洲以外的欧洲或北美接受初级职业培训。此外,大多数(52%)儿科外科项目每次培训只有一到两名培训人员,45%的项目没有定期培训人员[15]。这些数据强调,有必要加强中低收入国家的本地儿科外科培训项目,此外,还需要建立可持续的国际培训和交流机会,以补充现有的培训项目。

科学研究

可靠的研究有潜力改善临床实践,建立互利合作,为卫生政策提供信息,并增加培训机会。来自世界各地(包括高、中、低收入国家)的同事之间的研究合作已经助力了关于全球健康和全球外科高质量且有影响力的证据的发表。然而,文献表明,全球外科研究存在一定程度的不平等[36]。2014年,Elobu和同事对43名乌干达培训生进行了一项调查,以确定他们对国际合作的看法。只有15%的受训者认为国际或访问团体所进行的研究与乌干达的国家利益相一致,尽管28%的受访者确实参与了一项或多项此类研究活动,但他们都没有在随后的出版物中获得作者身份[37]。在Elobu等人的另一项研究中,绝大多数(n = 33,94%)的乌干达麻醉和外科培训生报告说,科研对他们的职业发展很重要,85%的人想发表论文[38]。然而,大多数学员认为他们的学位论文是一个经济负担,因为在81%的奖学金获得者中,只有35%[38]能支付研究费用。除了阻碍全球儿童外科高质量研究的个人或学员层面的因素外,许多系统层面的因素也可能阻碍进展。自LGoCS报告发表以来,在收集关于获得及时手术、围手术期死亡率和成人其他指标的基线手术、麻醉和产科数据方面取得了令人印象深刻的进展[39,40]。然而,很少有全球性的研究专注于确定儿童外科手术的指标或指标[1,4,5,17,41]。全球外科学界在儿童外科疾病的准确负担、围手术期结果、手术积压、成本效益和LGoCS指标方面的认知仍不足。需要患者、医疗提供者、社区、政府和国际组织共同努力来回答这些基本问题。

经费

Chao和他的同事进行的系统综述在消除“手术太昂贵”的传言中发挥了关键作用[42]。他们注意到,唇腭裂修复(每DALY 47.74美元)、普通外科(每DALY 82.32美元)、脑水手术(每DALY 108.74美元)和眼科手术(每DALY 136美元)的成本-效果比中位数与卡介苗疫苗(51.86-220.39美元)[42]相似。此外,他们还得出结论,在资源有限的国家,许多必要的外科手术是非常划算的。在此基础上,Saxton等人对中低收入国家的儿童外科手术进行了经济分析。这篇综述的研究结果表明,9种儿科手术平均每次手术带来的经济效益超过10,000美元[43]。作者使用人力资本方法计算了手术治疗获得的社会经济效益,该方法将人的生命价值折合为个人在预期寿命内产生的经济产出的贴现市场价值。这些数据再次强调,外科手术是全球卫生领域最具成本效益的干预措施之一,成本效益比为1:10[44]。中低收入国家儿童外科护理模式有待完善。在许多中低收入国家,手术费用是自付的。Saing报告说,在14个亚洲国家中,12个国家实行了自付手术程序,只有9个国家(45个)增加了健康保险条款。此外,几乎所有国家都提供政府补贴的外科治疗;然而,很难确定其医疗保健的质量和水平是否与私人保健机构相当[45]。

成就

尽管全球儿童外科面临上述挑战和不足,但社区在努力改善儿童获得安全手术和麻醉护理方面取得了多个重大里程碑式成就。目前各方正在共同努力,加强中低收入国家全球儿童外科手术的外科和麻醉工作人员。越南和印度正在举办短期培训课程,旨在提高普通儿童外科手术相关的理论知识和技能[46,47]。此外,一项对泛非基督教外科医生学会(PAACS)培训的非洲外科医生进行的为期20年的随访研究表明,所有这些外科医生仍在非洲执业[48]。一些国际组织还牵头解决儿童外科手术中存在的严重劳动力和基础设施不足问题。例如,总部设在苏格兰的非政府组织KidsOR一直致力于在世界上一些资源最有限的地区建立手术室和围手术期护理单位[49]。目前,他们的努力已经促成了超过2.4万例挽救生命的手术,避免了40多万DALY,带来了80多亿美元的经济效益[49]。

全球儿童外科领域的研究也取得了重大进展。GlobalSurg和GlobalPaedSurg是多机构、国际合作的成果,汇集了研究人员、外科医生、麻醉师、护士和其他医疗保健提供者,目的只有一个,即了解儿童外科手术的现状并进行改善[50,51]。此外,国家外科、产科和麻醉计划(NSOAPs)的引入和发展已经成为全球外科界的一项重大成就。最近,在NSOAPs中强调了强制纳入儿童手术的具体建议[52]。巴基斯坦和尼日利亚是第一批积极将儿童手术纳入其NSOAP程序的国家[52]。也许最重要的是全球儿童手术倡议(GICS)——一个由医疗保健提供者组成的联盟,积极倡导并努力确保全世界儿童的手术安全。GICS将在研究、倡导和培训等方面支持LMIC的提供者和同事,特别是培训人员[53]。GICS发布了儿童外科护理最佳资源(OReCS)文件,其中详细说明了在各级医院护理中为所有儿童提供最佳外科护理所需的资源[54,55]。目前,GICS一直致力于促进地方解决方案,吸引地方提供者,与机构、组织、医疗保健提供者和其他利益攸关方形成多种伙伴关系,并带头创建一个每个儿童都能获得安全和及时手术的世界。

结论

过去五年,全球对外科手术的兴趣和投资不断增加。尽管从历史上看,全球儿童外科手术的发展势头一直缓慢,但最近的努力已经转化为社区的巨大进步。从医务工作者数量,到培训和教育、科研和经费,仍有许多方面的工作需要完成。儿童外科护理提供者和其他相关利益攸关方面临的挑战可能令人生畏,但最近的成就强调了优先考虑每一个儿童健康的重要性。不能让任何一个孩子掉队,只有这样,我们才能真正实现SDG-3,并积极减少新生儿、儿童和青少年的发病率和死亡率。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Dominique Vervoort) for the series “Global Surgery” published in Journal of Public Health and Emergency. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-2020-gs-08. The series “Global Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Both authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mullapudi B, Grabski D, Ameh E, et al. Estimates of number of children and adolescents without access to surgical care. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:254-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaneda T, Bietsch K. World Population Data Sheet (2015). Population Reference Bureau 2015. Available online: http://www.prb.org/pdf15/2015-world-population-data-sheet_eng.pdf%0Ahttp://www.jstor.org/stable/1972177?origin=crossref

- Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386:569-624. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith ER, Vissoci JRN, Rocha TAH, et al. Geospatial analysis of unmet pediatric surgical need in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1691-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butler EK, Tran TM, Nagarajan N, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric surgical needs in low-income countries. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170968 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ologunde R, Maruthappu M, Shanmugarajah K, et al. Surgical care in low and middle-income countries: Burden and barriers. Int J Surg 2014;12:858-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beard JH, Ohene-Yeboah M, deVries CR, et al. Hernia and Hydrocele. In: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery. The World Bank, 2015:151-71. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333501/

- Owen RM, Capper B, Lavy C. Clubfoot treatment in 2015: A global perspective. BMJ Global Health 2018;3:e000852 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farmer D, Sitkin N, Lofberg K, et al. Surgical Interventions for Congenital Anomalies. In: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery. The World Bank, 2015:129-49.

-

Health - United Nations Sustainable Development - Colin Mathers TB and DMF. The global burden of disease 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008:146.

- Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, et al. Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery. Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery. The World Bank, 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333500/

- Lalchandani P, Dunn JCY. Global comparison of pediatric surgery workforce and training. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:1180-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswami S, Nwomeh BC, Ameh EA. The pediatric surgery workforce in low- and middle-income countries: Problems and priorities. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:32-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chirdan LB, Ameh EA, Abantanga FA, et al. Challenges of training and delivery of pediatric surgical services in Africa. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:610-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui S, Vervoort D, Peters AW, et al. Closing the gap of children’s surgery in Pakistan. World J Pediatr Surg 2019;2:e000027 [Crossref]

- Hamad D, Yousef Y, Caminsky NG, et al. Defining the critical pediatric surgical workforce density for improving surgical outcomes: a global study. J Pediatr Surg 2020;55:493-512. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vansell HJ, Schlesinger JJ, Harvey A, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, obstetrics, and emergency care in Guyana. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2015;5:75-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozgediz D, Kijjambu S, Galukande M, et al. Africa's neglected surgical workforce crisis. Lancet 2008;371:627-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodges SC, Mijumbi C, Okello M, et al. Anaesthesia services in developing countries: Defining the problems. Anaesthesia 2007;62:4-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jochberger S, Ismailova F, Lederer W, et al. Anesthesia and its allied disciplines in the developing world: A nationwide survey of the Republic of Zambia. Anesth Analg 2008;106:942-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz G, Detlefs S, Kelly McQueen KA. Global anesthesia workforce crisis: A preliminary survey revealing shortages contributing to undesirable outcomes and unsafe practices. World J Surg 2010;34:438-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holmer H, Lantz A, Kunjumen T, et al. Global distribution of surgeons, anaesthesiologists, and obstetricians. Lancet Global Health 2015;3:S9-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswami S, Nwomeh BC, Ameh EA. The pediatric surgery workforce in low- and middle-income countries: Problems and priorities. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:32-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gajewski J, Bijlmakers L, Mwapasa G, et al. ‘I think we are going to leave these cases’. Obstacles to surgery in rural Malawi: a qualitative study of provider perspectives. Trop Med Int Health 2018;23:1141-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burch VC, McKinley D, van Wyk J, et al. Career intentions of medical students trained in six Sub-Saharan African countries. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2011;24:614. [PubMed]

- Ozgediz D, Langer M, Kisa P, et al. Pediatric surgery as an essential component of global child health. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:3-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chew YW, Rajakrishnan S, Low CA, et al. Medical students' choice of specialty and factors determining their choice: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey in Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Malaysia. Biosci Trends 2011;5:69-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deedar-Ali-Khawaja R, Khan SM. Trends of surgical career selection among medical students and graduates: A global perspective. J Surg Educ 2010;67:237-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bland KI, Isaacs G. Contemporary trends in student selection of medical specialties: The potential impact on general surgery. Arch Surg 2002;137:259-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani M, Dhafery B, Al Mulhim M, et al. Factors influencing Saudi medical students and interns' choice of future specialty: a self-administered questionnaire. Adv Med Educ Pract 2014;5:397-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farmer DL. Standing on the shoulders of giants: A scientific journey from Singapore to stem cells. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:15-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanfey H, Hollands C, Gantt NL. Strategies for building an effective mentoring relationship. Am J Surg 2013;206:714-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Healy NA, Cantillon P, Malone C, et al. Role models and mentors in surgery. Am J Surg 2012;204:256-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Jesus LE, Aguiar AS. Needs and specialization for pediatric surgeons in Brazil. Rev Col Bras Cir 2009;36:356-61. [PubMed]

- Sgrò A, Al-Busaidi IS, Wells CI, et al. Global Surgery: A 30-Year Bibliometric Analysis (1987-2017). World J Surg 2019;43:2689-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, et al. Evaluating international global health collaborations: Perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery 2014;155:585-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, et al. Research in surgery and anesthesia: Challenges for post-graduate trainees in Uganda. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2015;28:11-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fatima I, Shoman H, Peters A, et al. Assessment of Pakistan’s Surgical System by Tracking Lancet Global Surgery Indicators Toward a National Surgical, Obstetric, and Anaesthesia Plan. J Am Coll Surg 2019;229:S125. [Crossref]

- Hanna JS, Herrera-Almario GE, Pinilla-Roncancio M, et al. Use of the six core surgical indicators from Lancet Commission on Global Surgery in Colombia: a situational analysis. Lancet Global Health 2020;8:e699-710. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poenaru D, Seyi-Olajide JO. Developing Metrics to Define Progress in Children’s Surgery. World J Surg 2019;43:1456-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chao TE, Sharma K, Mandigo M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery and its policy implications for global health: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet Global Health 2014;2:e334-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saxton AT, Poenaru D, Ozgediz D, et al. Economic analysis of children’s surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165480 [Crossref] [PubMed]

-

Surgery - Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries - NCBI Bookshelf - Saing H. Training and delivery of pediatric surgery services in Asia. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11083433/

- Holterman AX. Deploying Pediatric Acute Surgical Support (PASS)-an interdisciplinary multimodal course for initial response to life-threatening pediatric surgical emergencies. Available online: https://pediatrics-neonatology-conferences.magnusgroup.org/program/scientific-program/deploying-pediatric-acute-surgical-support-pass-an-interdisciplinary-multimodal-course-for-initial-response-to-life-threatening-pediatric-surgical-emergencies

- Madhuri V, Stewart RJ, Lakhoo K. Training of children’s surgical teams at district level in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Available online: https://journals.lww.com/ijsgh/Fulltext/2019/10000/Training_of_children_s_surgical_teams_at_district.2.aspx

- Van Essen C, Steffes BC, Thelander K, et al. Increasing and Retaining African Surgeons Working in Rural Hospitals: An Analysis of PAACS Surgeons with Twenty-Year Program Follow-Up. World J Surg 2019;43:75-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Research and Impact | KidsOR. Available online: https://www.kidsor.org/what-we-do/research-and-impact/

-

About GlobalSurg - Globalsurg -

About the Study - Global Paed Surg - Peters AW, Roa L, Rwamasirabo E, Ameh E, et al. National surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia plans supporting the vision of universal health coverage. Vol. 8, Global Health Science and Practice. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7108944/

- Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery. Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery: A Model of Global Collaboration to Advance the Surgical Care of Children. World J Surg 2019;43:1416-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goodman LF, St-Louis E, Yousef Y, et al. The Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery: Optimal Resources for Improving Care. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2018;28:51-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery. Optimal Resources for Children’s Surgical Care: Executive Summary. World J Surg 2019;43:978-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

韩璐

首都儿科研究所医学硕士研究生在读。目前从事儿科消化道疾病相关研究。2020年以第一共同作者身份发表SCI论文一篇,2021年以第一作者身份在核心期刊发表综述一篇。(更新时间:2021/9/13)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Abbas A, Samad L. Children at the heart of global surgery: children’s surgery in low- and middle-income countries. J Public Health Emerg 2020;4:34.