Why Sudanese doctors should consider research career or PhD degree after their postgraduate medical training?

Introduction

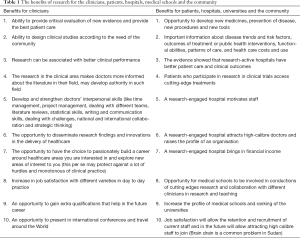

Over the last hundred years of medical education in Sudan, the main focus was in clinical training. Those who went in research or acquired research degrees mainly stem from their personnel choice and enthusiasm. However, the majority or almost all Sudanese doctors have that secret love for research and publications. Perhaps the fact that its time-consuming industry and the majority of clinicians have to work in private clinics to support their families have made that affection for research deeper but for the majority not possible to achieve. The benefits of research for the clinicians, community, patients and hospitals and medical schools and universities are enormous and this can be seen in Table 1 (1-5). Conduction of research is also important as the recent change in the political system is expected to bring revolutionary changes in term of medical education and postgraduate medical training. Ultimately, this may enhance the research output of all medical schools in Sudan. In this review we have discussed what type of research is needed in Sudan, why doctors in Sudan need to do research and why doctors in Sudan need to consider PhD degree. We present the following article in accordance with the Journal of public Health and Emergency reporting checklist.

Full table

Methodology

We have performed an electronic searched of PubMed, Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar for English published literature during the last three decades, we used the keywords: medical education in Sudan, medical postgraduate in Sudan, medical school and MD-PhD programme. We have also searched for the benefits of PhD programme in general and in particular for medical doctors.

What type of research is needed in Sudan?

The type of research we recommend for all doctors at this stage in the history of Sudan and the next 10 years is populations clinical studies research. This type of research can be either observational studies or clinical trials. The observational studies involve cross-sectional study, prospective cohort study, case-control study and the nested case-control study (6). Sudan is a large country inhabited by different ethnic groups and populations, and clinical population research may yield exciting data. Also, certain diseases are related to habits and traditions and research in patient education and preventative medicine can be essential factors (7,8). This can also lead to a more scientific understanding of different tribes and populations. Importantly, genetic factors and their roles in diseases in Sudan is not fully understood and explored (8,9). The population studies will also not cost a significant amount of money on a similar scale to lab-based research using state of the art methods and expensive equipment with a high cost of maintenance and turn offer. Therefore, community-oriented research is what is needed in Sudan.

Why doctors in Sudan need to do research?

It is expected that engagement in research will lead to the development of an environment where doctors can look for the appraisal for their data in comparison with international data and this will enhance the culture of looking for new evidence and engagement with recent advances in medicine and sciences (10). The important part of the population studies is the fact that this involves different teams and peoples with different skills, not necessarily related directly to medicine as a profession like a statistician. Therefore, this will also come with the benefits of learning to work in one team and multidisciplinary approach (10).

In the view of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible to suggest that further research is urgently needed to understand and research more about COVID-19 in Sudan. Nobody can predict whether the second wave of COVID-19 will occur or not, and it’s not clear whether different pandemics can occur. COVID-19 also showed the importance of research in social science and medical education such an interdisciplinary collaboration can yield into a new and unique outcome and further fostering to collaboration in research. For instance, most of the medical education is now online and experience in this field is important and crucial. Engaging in research will increase doctor’s personnel satisfaction due to an increase in interest in learning, and the feeling of developing that intellectually curious attitudes towards challenges rising from the current communicable and non-communicable disease in Sudan. Besides all these benefits, research will come with benefit of enhancing skills in writing and publication. Ultimately this will increase the contribution of Sudan towards the global medical research output and also allow Sudanese doctors to attend and contribute to international conferences by submitting abstracts in different fields of medicine. This will increase the chance of Sudanese researchers to attract international collaborations and possibly international research grants.

This will also help Sudanese Diaspora who are engaged in research in different countries like USA, UK and Gulf countries to collaborate with Sudan and involve in knowledge transfer. Abdalla et al. identified the benefit of Sudanese diaspora to the health system in Sudan (11). Interestingly, other African medical diasporas also contributed to the health system in their countries, while the Somali-Swedish global health initiative was about rebuilding research capacity in fragile states (12,13). It worth mentioning, that the main hinders for the establishment of research in Sudan are the lack of funding and time to be dedicated for research (14).

Why doctors in Sudan need to consider PhD degree after their medical speciality?

The only way for training in the medical speciality in Sudan is through Sudan Medical Specialization Board (SMSB) which can extend from 4–6 years in any medical speciality. While exposure to scientific research starts from the final years in medical schools where medical students get assigned to research methodology courses and summited their dissertation before graduation. Nowadays, publications by medical students and fresh graduates in Sudan start to show in national and international journals, and research environments become more helpful through various research groups that dominated by medical students and early career doctors.

The training is extensive and involves significant work load. At the moment there is no programme for offering dual training in the research and clinical practice. It worth mentioning at the end of the final year in training with SMSB, doctors have to complete a research thesis before the end of their training. This will not be on a similar scale to the research experience as a PhD degree. The combination of medical speciality with PhD degree will allow clinicians to have unique career pathway. This because such combination of clinical and research experience will create the passion of researching medical problems and challenges and fuel that ambition and desire to understand the mechanism of disease and ultimately this may help in the management of the diseases (15). Therefore, SMSB can assess the benefit and practicality of offering such an opportunity for Sudanese doctors. This for postgraduate training only and not similar to undergraduate programme in Western countries (16). Such type of program will be difficult to implement in Sudan as this will involves radical changes in the undergraduate curriculums and necessitate significant experience in medical education. In addition, to other challenges such as needs for mentoring, facilitating integration with students in each phase, integrating the curriculum to foster mastery of skills needed for each phase, awareness of the educational differences between MBBS and PhD training, and support needed. We have not elaborated in details about the steps needed for the implementation of the clinical postgraduate MD-PhD programme as we feel this can be beyond the scope of this review.

In Table 2 we highlighted the benefits Sudanese doctors may gain from being involved in a PhD degree. The experience doctors can gain from working in common medical, educational or social issues in Sudan can be enormous and may extend beyond the list we have provided in Table 2. This may ultimately provide an opportunity to ignite research interest and enthusiasm in young doctors and they may seek to research this medical, educational or social problems inside Sudan for the rest of their medical career. This can be extremely beneficial for patients in Sudan, the community as a whole and also the medical education in Sudan. Generally speaking, there is extreme shortage of physician-scientist in Africa and Middle East (17-19).

Full table

It worth mentioning that the common problems that also faced by doctors in Western countries could also occur in Sudan during studying for PhD degree: longer duration of the training, the long hours of working alone, less financial income, less time for family, finding suitable supervisor, funding for research and decrease in opportunities to attend and participate in international conferences. Overcoming these challenges may provide good skills to survive the future journey as physician-scientist. Our sincere suggestion before you think of doing PhD you will need to ask yourself two questions. The first question: Are you doing the PhD for the sake of personal and professional benefits only or you want to continue with research as life long career? The second question: Are you fulfilling the criteria listed in Table 3 which explain the student qualities for research? (20) If you think you meet most or all of these criteria, you will likely be successful in your future research career. Some of these criteria are essential, while others can be acquired. For instance, diligence and hard work are necessary during the PhD course or research career. They can be gained through strong work ethics, discipline, focus, efficiency and professionalism. Over the years this will be part of the normal nature for the researcher. While self-motivation is the essential component that will provide momentum for the long journey. Not having most of the qualities mentioned in Table 3 may slow the candidate progress with a PhD course, or he/she may not complete the course. Importantly, best clinical practice is based on research and evidence-based medicine. Therefore, we encourage all Sudanese doctors to make the most of the currently available research opportunities, not only for personnel and profession benefits but also in contributing to the health of Sudanese nation in urban and rural areas and those living in the remote areas.

Full table

Conclusion

Being a doctor is a career of lifelong learning and teaching in medical school, during the ward rounds and in a research setting. In the world of technology and internet revolution, the world becomes like a small village. Therefore, to keep with rapid development in medical information and address future challenges like a pandemic of COVID-19, enriching the research opportunities and open more opportunities for doctors to do a PhD will significantly increase effectiveness of clinical practice in Sudan. The combined degree of PhD and clinical MD will increase the number of clinical scientists (physician-scientists) in Sudan. The benefits of such programme for Sudan can be seen in the following: (I) increase the numbers of young doctors with research experience (II) young researchers are always equipped with energy and enthusiasm to explore and test theories (III) young researches are likely to stay in one field or one research for next 20–30 years and this may allow them to gain national and international recognition for their academic institutes and Sudan (IV) Besides, Sudan has rare and neglected tropical diseases and an increase in non-communicable diseases, there is an urgent need to conduct more research in the field of COVID-19. (V) such programme will enhance and strengthen the conduction of research in medical schools in Sudan.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ahmed would like to dedicate his contribution in this manuscript for his mother (Fatima Mohamed Khalil) who died on 13/12/2020.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Public Health and Emergency for the series “What the Future Holds for Medical Education in Sudan”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-20-90). The series “What the Future Holds for Medical Education in Sudan” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. NEH served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Phillips E, Pugh D. How to get a PhD: A handbook for students and their supervisors. McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2010.

- Laidlaw A, Aiton J, Struthers J, et al. Developing research skills in medical students: AMEE Guide No. 69. Med Teach 2012;34:754-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Von Stumm S, Hell B, Chamorro-Premuzic T. The hungry mind: Intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci 2011;6:574-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furnham A, Monsen J, Ahmetoglu G. Typical intellectual engagement, Big Five personality traits, approaches to learning and cognitive ability predictors of academic performance. Br J Educ Psychol 2009;79:769-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGrail MR, O'Sullivan BG, Bendotti HR, et al. Importance of publishing research varies by doctors’ career stage, specialty and location of work. Postgrad Med J 2019;95:198-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gosall NK, Gosall GS. The doctor's guide to critical appraisal. PasTest Ltd; 2012.

- Boulassel MR, Al-Farsi R, Al-Hashmi S, et al. Accuracy of platelet counting by optical and impedance methods in patients with thrombocytopaenia and microcytosis. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 2015;15:e463 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charani E, Cunnington AJ, Yousif AH, et al. In transition: current health challenges and priorities in Sudan. BMJ Global Health 2019;4:e001723 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hassan HY, van Erp A, Jaeger M, et al. Genetic diversity of lactase persistence in East African populations. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauer KW, Liang Q. The effect of personality and precollege characteristics on first-year activities and academic performance. Journal of College Student Development 2003;44:277-90. [Crossref]

- Abdalla FM, Omar MA, Badr EE. Contribution of Sudanese medical diaspora to the healthcare delivery system in Sudan: exploring options and barriers. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nwadiuko J, James K, Switzer GE, et al. Giving Back: A mixed methods study of the contributions of US-Based Nigerian physicians to home country health systems. Global Health 2016;12:33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalmar AA, Hussein AS, Walhad SA, et al. Rebuilding research capacity in fragile states: the case of a Somali–Swedish global health initiative: Somali–Swedish Action Group for Health Research and Development. Global Health Action 2017;10:1348693 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Auf AI, Awadalla H, Ahmed ME, et al. Comparing the participation of men and women in academic medicine in medical colleges in Sudan: A cross-sectional survey. J Educ Health Promot 2019;8:31. [PubMed]

- Students-residents.aamc.org. 2020. Why Pursue An MD-Phd?. Available online: https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/article/why-pursue-md-phd/ [Accessed 17 September 2020].

- Barnett-Vanes A, Ho G, Cox TM. Clinician-scientist MB/PhD training in the UK: a nationwide survey of medical school policy. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009852 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adefuye AO, Adeola HA, Bezuidenhout J. The physician-scientists: rare species in Africa. Pan Afr Med J 2018;29:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Zaid A, Alamodi AA, Alkattan W, et al. Dual-degree MBBS–PhD programs in Saudi Arabia: A call for implementation. Med Teach 2016;38:S9-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Zaid A, Altinawi B, Eshaq AM, et al. Interest and perceived barriers toward careers in academic medicine among medical students at Alfaisal University–College of Medicine: A Saudi Arabian perspective. Med Teach 2018;40:S90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otago.ac.nz. 2020. Perspectives On Quality Candidates, For Students, Graduate Research School, University Of Otago, New Zealand. Available online: https://www.otago.ac.nz/graduate-research/study/otago404001.html [Accessed 17 September 2020].

Cite this article as: Ahmed MH, Husain NE, Elsheikh M. Why Sudanese doctors should consider research career or PhD degree after their postgraduate medical training? J Public Health Emerg 2021;5:16.