A descriptive study exploring the worldwide involvement of medical students in the COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia, caused by a novel Coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) occurred in Wuhan, China. On March 11th, due to the accelerating levels of global disease transmission, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic (1). The number of cases at the time this article was written, has been accelerating with now more than 173 million confirmed cases in 219 countries worldwide, causing 3.7 million deaths as of the 4th of June 2021 (2).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led hospitals worldwide to find themselves acutely overburdened and understaffed as they work to limit the spread of the outbreak. This highlights the shortage of workforce and the need for sustainable investment in health systems including adequate training (3-9). All over the world, countries have undertaken drastic measures to prevent the further spread of the disease and contain the pandemic, including highly restrictive lockdowns, closing workplaces, public areas, as well as asking people to stay at home (10).

In line with these restrictive lockdown policies, many universities have suspended activities, generating unprecedented challenges for the delivery of medical education and forcing medical schools to decide how to proceed in the time of COVID-19, including the possible active involvement of Medical Students in both clinical and non-clinical settings. Moreover, responses to the pandemic in medical education have varied from country to country, from closures of medical schools to online/distance learning approaches to abiding by country-specific measures. As the number of cases of COVID-19 continues to increase and health systems become further overburdened, medical students may represent a valuable surge mechanism assisting with the “flatten the curve” public health initiatives to curtail transmission. Ranging from public health awareness initiatives to active participation in the COVID-19 workforce, it is imperative to understand the possible roles medical students may undertake during global health emergencies (11-13).

Currently, there is a paucity of research on the role of medical students in pandemics and global emergencies as well as medical schools’ responses to these sudden lockdowns caused by COVID-19 to guide institutions to make evidence-based decisions. A recent literature review provides new insights, looking at the role of medical students during past emergencies, including the Ebola outbreak and the SARS epidemic. The roles medical students played varied from patient care, raising awareness, triage, telephone helplines, to manual ventilation and logistical assistance. The review concluded that medical students can contribute and are willing to get involved during emergencies, but more research is needed regarding the impact on medical students themselves (14).

The aim of this study is to assess the current practices and roles assumed by medical students worldwide during the pandemic. To provide an overview and reflection of current practices globally for the use of institutions during this pandemic and future global health emergencies. We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-21-28).

Methods

A global quantitative, descriptive study was conducted in April 2020 to assess the different roles that medical students filled during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection tool was developed by the authors after a thorough review of the literature and analysis of perspectives. The questionnaire was pre-tested through a pilot survey performed in March and questions were adapted to improve reliability, sensitivity and validity. Due to the circumstances surrounding the pandemic, the questionnaire was disseminated as an online version on google forms, through all personal and organisational social media platforms of the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations (IFMSA) consisting of social media pages and mailing servers reaching medical students from 129 countries across the globe.

Non-random availability sampling was used and inclusion criteria of the study included any medical students currently in the course of their studies and recent medical graduates. Graduates for more than 3 months or other health professions students were excluded from the target sample. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from every participant containing information on the purpose of the research, its procedures, the time required, the risks and benefits involved, data confidentiality, information on how to withdraw, and contact information of the researchers.

The self-administered questionnaire consisted of four different sections. The first section asked for demographic information. The second section focused on the current roles of medical students at the respondents’ medical schools including questions on the organisation and safety of the roles. The third section included opinion-based questions including questions on wellbeing. Finally, the fourth section asked respondents what they think the ideal role of a medical student during a pandemic is. The research was authorised and approved by the IFMSA Executive Board. As per consultation of the Medical Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres of the University of Amsterdam, further ethical approval was deemed not necessary. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Statistical analysis

Results were automatically inputted into an Excel spreadsheet. Qualitative and quantitative data was analysed separately and certain questions were grouped. Data analysis was undertaken using IBM SPSS, Microsoft Excel, RQDA and Nvivo. Quantitative data analysis consisted of counting frequencies of responses, both in number and percentage. This was repeated whilst separating responses based on income-level of the respondents’ country as well. Thematic analysis of qualitative data was done. The authors created overviews of the respondents’ answers identifying general themes for each question. The agreed themes were consequently used to code the answers by AM and KP using NVivo and RQDA. By using the codes, the programme was able to generate and identify the most common issues that are mentioned in the qualitative data.

Results

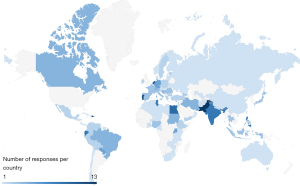

A total of 279 responses were received. Respondents studied in 101 different countries, at 209 different universities, representing all six UN Regions as shown in Figure 1. 63.4% of respondents studied in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) (n=177), 36.6% of respondents studied in High-Income Countries (HICs) (n=102). The respondents were from all different stages of their medical studies ranging from year 1 to year 8, to recent medical graduates.

The roles of medical students during the pandemic

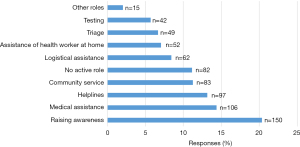

The roles that medical students played during the COVID-19 pandemic are depicted in Figure 2. The three most common reported roles were raising awareness (n=150, 20.3%), providing medical assistance (n=106, 14.4%) and working at helplines (n=97, 13.1%). In total, respondents reported 740 different roles, indicating that medical students play different types of roles at the same medical schools. Figure 3A shows the division of roles in LMICs versus HICs, controlled for the number of responses per category. In LMICs, community service (n=61, 62.6%), raising awareness (n=109, 60.5%) and having no active role (n=58, 58.2%) were more often reported. In HICs the roles of testing (n=30, 82.6%), assisting a health worker at home (n=36, 80.6%) and logistical assistance (n=38, 74.1%) were more often reported.

Through qualitative assessment of students’ opinions on their current role, we received both positive and negative comments. The most common negative comment mentioned by 34 participants was the feeling that they can do more to help in the pandemic. Other negative comments included lack of personal protective equipment, lack of organisation, no supervisor and not feeling trained for the role. The most common positive comment by 11 participants was feeling proud that they are helping, other comments included the experience being a useful learning opportunity, the work not being stressful and being trained for the role.

Role organisation and details

In regard to triage (n=47, 16.9%), medical assistance (n=69, 24.5%), testing (n=60, 21.5%) and logistical assistance (n=103, 36.9%) coordination, governments were the main coordinators, followed by universities. Additionally, governments were the main coordinators of helplines (n=61, 21.9%), followed by students (n=43, 15.4%). Furthermore, students were the main coordinators for community service (n=69, 24.7%) as well as assistance of health workers at home (n=47, 16.9%).

When exploring the role organisation, we focused on the financial and academic benefits to the student. The majority of students stated that they were taking part in an unpaid role (n=172, 61.8%), with 15.4% of students stating that they were being paid (n=43). The most common unpaid roles were raising awareness (n=154, 79.4%) and community service (n=118, 69.0%) and the most common paid roles were medical assistance (n=66, 34.2%) and triage (n=29, 18.7%). 7.7% of the reported roles were mandatory (n=22) and 78.6% were voluntary (n=219). The most common mandatory role being medical assistance (n=40, 21.1%) and the least common being raising awareness (n=9, 4.5%) and assisting health workers at home (n=8, 4.7%). Finally, 9.4% of students received academic recognition for their roles (n=26), the most common role which did receive academic recognition was medical assistance (n=59, 21.05%).

Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that medical students should receive payment for triage (n=199, 71.4%), medical assistance (n=217, 77.7%), testing (n=200, 71.8%), logistical assistance (68.6%), assisting a health worker at home (n=151, 54.0%), and working at helplines (n=163, 58.6%) as depicted in Figure 3B. For all roles, most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that medical students should receive academic recognition, with the top three roles being medical assistance (n=229, 82.2%), triage (n=216, 77.3%) and testing (n=211, 75.7%) as depicted in Figure 3C.

Thematic analysis of students’ ideal role also found several organisational comments that need to be ensured when organising roles for students. 20.8% of respondents indicated that they are aware of an official protocol and/or statement issued on the role of medical students during the pandemic. Other points mentioned included being paid or receiving academic credit, having a choice as to what role to play, have mental health support as well as the availability of official regulations to protect the students when working.

Student safety and wellbeing

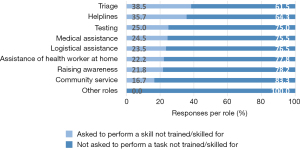

Out of 172 respondents that played an active role, 18.6% had been asked to perform a role that they had not been trained in and/or did not feel skilled enough to perform (n=32). The roles that were most reported in which students had been asked to perform such a skill, were triage (38.5%), helplines (35.7%), and testing (25.0%), as shown in Figure 4. When asked if medical students at their medical schools were safe performing their role, 47.6% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed, whilst 23.8% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, as shown in Figure 5A.

When asked how their role during the pandemic impacted their wellbeing, 44.8% of respondents stated that their role had a positive (n=93, 33.3%) or very positive (n=32, 11.5%) impact. 108 respondents stated the role had no impact on their wellbeing (38.7%). 16.5% respondents indicated that their role had a negative (n=38, 13.6%) or very negative (n=8, 2.9%) impact on their wellbeing. Figure 5B outlines the impact on wellbeing per role. It shows that having no role had the most negative impact on wellbeing, followed by testing and helplines. Assisting a health worker at home had no negative impact on wellbeing.

The students were further asked to describe the impact of their current roles on their well being if they wished to. Qualitative data analysis of these responses was made, the results of which can be found in Table 1. Among the responses, comments associated with positive feelings were identified 170 times, while comments associated with negative feelings were identified 141 times. Of the 248 responses received, 76 (30.6%) responded that they felt a sense of purpose in being able to contribute during the pandemic. On the contrary, 29 (11.7%) comments were identified to indicate that students felt ‘useless’ or ‘purposeless’ because they had no role to play.

Table 1

| Impact of current role on students’ wellbeing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | n | Negative | n |

| Felt a sense of purpose to be contributing in some way | 76 | Felt no sense of purpose for being unable to contribute | 29 |

| Felt good to help people/community | 30 | Concerned about their/their family’s safety | 20 |

| Felt good to be learning new skills/finding time to study | 26 | Found work stressful | 17 |

| Felt safe to be at home | 19 | Unhappy with current role | 15 |

| Found it good to keep busy | 14 | Unhappy with being unable to continue work/study | 10 |

| Felt good to have time for themselves | 5 | Felt pressured with university work | 6 |

| Felt like they had too much responsibility | 2 | ||

| Felt like they were not appreciated for their work | 2 | ||

Medical students’ opinions on their role

42.3% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that medical students at their medical school were playing the best role they can during the pandemic, whilst 34.1% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement, as depicted in Figure 5A. When breaking down these responses per role, Figure 5C shows respondents are most positive about logistical assistance, community service and medical assistance. Respondents agreed the least with this statement when medical students played no active role.

The results for the question asking students to comment on how they feel about their current role saw both positive and negative responses. Direct positive comments about the role were identified 24 times and direct negative comments were mentioned 21 times. The most common reason for feeling positively towards their role was the opportunity to help others and feeling proud. Thirteen participants explicitly stated that they would be willing to help if they had the opportunity, and 34 participants wrote that they are not doing enough and “can do more”.

We specifically asked participants to share their opinion on the ideal role of a medical student during the current pandemic. Since this was an open-ended question, a proportion of responses focused exclusively on organisational points, while others suggested a specific role or roles. The most common role mentioned was raising awareness and educating the public. This was followed by clinical roles, although most responses did not specify whether this should be a COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 related clinical role, seven participants directly suggested for the clinical roles to be non-COVID related.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our study highlights that medical students play a range of different roles during this pandemic. The most common roles being raising awareness, medical assistance, helplines and community service.

The findings show that medical students are willing and motivated to take active part in helping during the pandemic. This reflects the range of potential that medical students can indeed have in pandemic situations.

Findings in context

Medical students have been described to help in emergency situations historically, ranging from being on the resuscitation teams or medical assistance after terrorist attacks, natural disasters or previous pandemics (15-18). Although they have been utilised in previous emergencies, identifying a clear role for medical students is lacking. In our study only 20.8% of participants were aware of a protocol or statement that described what students’ role should be. An example of such a protocol is the Association of American Medical Colleges’ ‘Guidance on Medical Students’ Participation in Direct In-person Patient Contact Activities’, which underlines the importance of student safety (19). The fact that only 20.8% of respondents were aware of such a protocol in their context, can lead to some knock-on effects, including students not being aware of how they can help and therefore losing on a valuable resource. Especially since we can expect more pressure on health systems in the future it is now imperative that institutions consider how to best utilise medical students in such emergency situations (20). These roles should be carefully planned with an active involvement of the medical student community to duly consider their values, preferences, and needs.

A recent systematic review exploring the role of medical students in pandemic situations, found similar results to our study (14). The most common role played in previous pandemics and health emergencies included logistics, medical assistance and education. One of the main challenges to students being involved is the lack of preparedness (14). This is similarly reflected in our findings, a large proportion of medical students had been asked to perform a role they did not feel skilled enough for or were not trained. The most common roles in which such skill had been asked for, were triage, helplines and testing. These three roles are imperative for successful public health intervention and control of the spread of disease (21-23). A study by Mortelmans et al. found that 18% of the students felt that they had sufficient knowledge in disease management in a disaster situation (24). Similarly, Gouda et al., found that 23.7% of students felt that they had sufficient skills to respond to an emergency outbreak (25). Asking medical students to practice skills they have not been trained in introduces many ethical dilemmas, for both the individual and the patient. The systematic review by Martin et al., found that only 3 out of the 28 included articles had a degree of training before the students underwent any role (14). Disaster preparedness and training need to be prioritised in medical curricula to ensure students are prepared and skilled when such situations arise in the future. If this is not possible, training before a role is adopted is crucial to ensure both patient, student and doctor safety.

Our results indicate differences in the roles that students most often play in HIC versus LMICs. Medical education and health governance systems vary greatly across the world. Each country should take into account its needs and resources to ensure the skills offered by medical students are utilised efficiently within the workforce. More research is needed to look into factors contributing to the difference in the design of roles for medical students.

There are stark differences between the bureaucracy of the roles both between and within countries themselves. This can have large ethical implications as medical students are not being treated equally for important and mentally consuming work. When taking into account students’ perspective, most agreed that they need to receive some form of compensation, most commonly monetary. Academic recognition comes with its own ethical dilemmas, most importantly, more vulnerable students or those with vulnerable families who are unable to volunteer during a pandemic would be affected negatively by not being able to receive academic recognition. A voluntary role with monetary compensation was the most ideal role students described, efforts to ensure this happens on a global level should be prioritised.

When asking students’ opinions about their involvement, the most negative comments received were from those who were not playing a role. Moreover, respondents indicated that their mental health was most negatively impacted when not playing a role. This reflects the willingness and need to help within the medical student cohort on an international level. Those who were not asked to play a role felt useless. Students also commonly stated that they were not playing the most appropriate role, either because they were unskilled to do so, or because they were not doing enough. In the future, the medical student pool should be efficiently used and students’ skill sets should be taken into account when acquiring their help.

Conclusions

To conclude, our results suggest that medical students have contributed and continue to contribute to the pandemic in many ways. These roles show a great amount of variability in their organization and execution. Our analysis also indicates that medical students are willing to contribute and that their wellbeing is most negatively impacted when they do not have a role to play. Our results are in line with results found by similar studies during past health emergencies (14). Medical students are willing and should therefore play a role in responding to public health crises, however, strong ethical consideration must be given to their wellbeing and safety when designing these roles.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Executive Board and the Director of The Standing Committee on Medical Education of the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations for their continued support in bringing this project to reality.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-21-28

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-21-28

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-21-28

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe-21-28). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work (including full data access, integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis) in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The research was authorised and approved by the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations Executive Board. As per consultation of the Medical Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres of the University of Amsterdam, further ethical approval was deemed not necessary. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 6]. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

- Coronavirus Update (Live): Cases and Deaths from COVID-19 Virus Pandemic - Worldometer [Internet]. [cited 2021 March 20]. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries

- Armocida B, Formenti B, Ussai S, et al. The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e253 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elorrio E, Arrieta J, Arce H, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: A call to action for health systems in Latin America to strengthen quality of care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 33, Issue 1, 2021, mzaa062. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/33/1/mzaa062/5848602

- Litewka SG, Heitman E. Latin American healthcare systems in times of pandemic. Dev World Bioeth 2020;20:69-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- OECD/WHO (2020), Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020: Measuring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage, OECD Publishing, Paris. Available online:

10.1787/26b007cd-en 10.1787/26b007cd-en - Al-Mandhari AS, Brennan RJ, Abubakar A, et al. Tackling COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Lancet 2020;396:1786-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller IF, Becker AD, Grenfell BT, et al. Disease and healthcare burden of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Med 2020;26:1212-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalid A, Ali S. COVID-19 and its Challenges for the Healthcare System in Pakistan. Asian Bioeth Rev 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data [Internet]. 2020 Mar 4 [cited 2020 Sep 6]. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- Taha MH, Abdalla ME, Wadi M, et al. Curriculum delivery in Medical Education during an emergency: A guide based on the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish 2020;9: [Internet]. [Crossref]

- Arandjelovic A, Arandjelovic K, Dwyer K, et al. COVID-19: Considerations for Medical Education during a Pandemic. MedEdPublish 2020;9: [Internet]. [Crossref]

- Rabe A, Sy M, Cheung WYW, et al. COVID-19 and Health Professions Education: A 360° View of the Impact of a Global Health Emergency. MedEdPublish 2020;9: [Internet]. [Crossref]

- Martin A, Blom IM, Whyatt G, et al. A Rapid Systematic Review Exploring the Involvement of Medical Students in Pandemics and Other Global Health Emergencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz CL, Gluck N, Maurizio A, et al. The medical student experience with disasters and disaster response. CNS Spectr 2002;7:604-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reyes H. Students' response to disaster: a lesson for health care professional schools. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:658-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abud AM, deArmas E, Leon N, et al. Ebola prevention to recovery: a student-to-student social media campaign. Ann Glob Health 2015;81:124. [Crossref]

- Patil NG, Chan Y, Yan H. SARS and its effect on medical education in Hong Kong. Med Educ 2003;37:1127-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Guidance on Medical Students’ Participation in Direct In-person Patient Contact Activities. Last updated August 14th, 2020. [cited June 13]. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/coronavirus/medical-education

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet 2019;394:1836-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Challen K, Bentley A, Bright J, et al. Clinical review: mass casualty triage--pandemic influenza and critical care. Crit Care 2007;11:212. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ranka S, Quigley J, Hussain T. Behaviour of occupational health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Occup Med (Lond) 2020;70:359-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal PJ. The Importance of Diagnostic Testing during a Viral Pandemic: Early Lessons from Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;102:915-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mortelmans LJ, Dieltiens G, Anseeuw K, et al. Belgian senior medical students and disaster medicine, a real disaster? Eur J Emerg Med 2014;21:77-8. [PubMed]

- Gouda P, Kirk A, Sweeney AM, et al. Attitudes of Medical Students Toward Volunteering in Emergency Situations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020;14:308-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Blom IM, Martin A, Viva MIF, Whyatt G, Parikh KS, Dafallah AAE. A descriptive study exploring the worldwide involvement of medical students in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health Emerg 2021;5:23.