Emergency surgery for uterine and bowel perforation resulting from an illegal induced unsafe abortion: a case report

Introduction

An unsafe abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy that is performed either by a person lacking the necessary skills, in an environment that does not fulfill to minimal medical standards, or both (1). It is an alarming and serious public health challenge, accounting for 4.7–13.2% of maternal mortality cases globally (1). According to the exception clause stated in the penal code Act 574 (revised 1997) section 312, induced abortion is illegal in Malaysia, except in cases when continuation of the pregnancy poses risks to the life of the pregnant woman, or affects her physical or mental well-being after a detailed assessment by a medical practitioner registered under the Medical Act 1971. Stigma against abortion, cultural and religion factors, lack of awareness of abortion legislation among health care professionals, and high cost of abortion services in the private sector could possibly lead to unsafe abortion among pregnant women (2). Complications of unsafe abortion are incomplete abortion, massive hemorrhage, sepsis, uterine perforation, genital injury or bowel injury. Uterine perforation and bowel injury are rare but potentially life-threatening if we fail to recognize them early, leading to treatment delay. Hereafter, we report a case of unsafe induced abortion complicated by uterine and bowel perforation, which was successfully managed at our center. The description of the case, comprising the clinical presentation and management, is discussed with an emphasis of prompt surgical intervention. We have also highlighted the public health concerns that preclude safe abortion in the community, and aim to promote awareness regarding the perils of unsafe abortion practices. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-21-46/rc).

Case presentation

A 21-year-old female with 11 weeks period of amenorrhoea presented with severe lower abdominal pain and persistent per vaginal bleeding for a week. She had no significant past medical or surgical history. Further careful inquiry revealed that she had an unplanned pregnancy. She had attempted self-induced abortion by consuming traditional medication a week prior to presentation. Subsequently, she underwent a surgical abortion in a private clinic two days prior. She is a factory employee who is single, and was afraid to raise the child due to financial constraints.

Upon assessment in the emergency department, she was febrile, septic looking, tachycardic and hypotensive. Physical examination revealed a tender abdomen with signs of peritonitis. A vaginal examination revealed minimal per vaginal bleeding and a congested cervix with some tears. Other systemic examinations were unremarkable. A urine pregnancy test was positive for pregnancy. Blood investigation showed leucocytosis, metabolic acidosis with acute kidney failure.

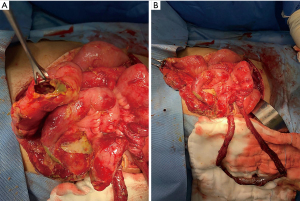

An ultrasound of the abdomen revealed an irregular shadow in the uterus with moderate collection in the peritoneal cavity, suggestive of incomplete abortion with suspicion of uterine perforation. Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated. An emergency laparotomy was undertaken. Intraoperatively, there was generalized feculent contamination of the peritoneal cavity. We found a single perforation at the posterior uterus, measuring about 1 cm × 1 cm (Figure 1). Besides that, there was a perforation at the ileum with a short segment of necrotic small bowel which was avulsed from its mesentery (Figure 2). Resection of the non-viable portion of the small bowel was performed followed by primary repair of the uterus. Peritoneal washout with a large amount of warm saline was performed. Both ends of resected ileum were left behind followed by temporary abdominal closure with negative pressure wound therapy. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to an intensive care unit (ICU) for normalization of physiology. Total parenteral nutrition was initiated. The patient’s condition greatly improved as evidenced by improvement of septic parameters, no metabolic acidosis and no inotropic support.

Re-laparotomy was done within 48 hours, and primary anastomosis of the small bowel was performed. Suction and curettage were done to remove the remaining product of conception. The uterus repair site remained intact. The patient was nursed in the ICU for the next few days before she was transferred out to the general surgical ward. She recuperated well, making an uneventful recovery, and was discharged after 2 weeks of admission. Prior to discharge, she was given psychological support and education of contraception. The patient remained asymptomatic at her first month follow up and compliant to oral contraceptive pills.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Patient perspective

Patient felt fortunate to survive through this event and appreciated all the efforts and treatments given by the doctors and nurses.

Discussion

Based on World Health Organization’s (WHO) report (1), it is estimated that 73.3 million induced abortions have occurred worldwide, but about 45% of all abortions were unsafe. While in Malaysia, the incidence of abortion is yet to be determined. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at USD 553 million (1). Unsafe abortion remains a public health concern, despite being one of the easiest preventable causes of maternal mortality and morbidity.

Pregnant women with unsafe abortion may present with features of incomplete abortion, per vaginal bleeding or septicemia (3). Major complications such as uterine perforation or bowel injury result in high mortality and morbidity. The uterus and the bowel can be injured by the surgical instruments such as curette or uterine sound when handled by inexperienced and unskilled personnel, especially in an unlawful setting. These major complications often go undetected during the procedure. The diagnosis of these iatrogenic injuries is made more difficult because of concealment of information by the pregnant women, due to the stigmatization of unsafe abortion. This leads to delayed presentation and diagnosis. The majority of patients become severely ill during the initial presentation, as shown in this case (4). A detailed history taking and thorough examination while maintaining professionalism, providing empathy with an unprejudiced mindset, will be helpful in establishing the diagnosis. To achieve a good outcome, optimal resuscitation, adhering to acute care guidelines, coupled with prompt surgical intervention, is essential (4,5). Initially, our patient was not forthcoming with the history of the unsafe abortion, which led to a delay in her diagnosis and treatment. Fortunately, with a high index of suspicion and non-judgmental detailed history taking, a correct diagnosis can be established.

Surgery is the gold standard in managing bowel and uterine perforation, following induced abortion (5,6). Delayed surgical intervention is associated with a poorer outcome. The common sites for bowel perforation are the ileum and sigmoid colon. The choice of definitive treatment varies from primary repair, bowel resection with primary anastomosis, to colostomy (4). The role of bowel anastomosis in a severe septic patient is debatable. The drawback for colostomy is the need for another surgery to restore intestinal continuity, and to deal with stoma complications. The damage control strategy for non-trauma emergency laparotomy proposed by Sohn et al. (7) was applied in this case. It is a staged procedure whereby involving the resection of the unhealthy bowel segment with blind end closure during the first surgery, followed by definitive reconstruction at a scheduled second laparotomy after 24–48 hours. It seemingly helps to improve the rate of bowel anastomosis. Re-exploration at a later period when the patient’s physiologic parameters improved, in terms of acidosis, inotropic support and coagulopathy. This allows the surgeon to have better and a clearer assessment prior to an eventual decision of anastomosis or performing a stoma. For our case, the patient was on high vasopressor support, severe metabolic acidosis, with the presence of generalized feculent contamination which precludes anastomosis to be performed safely. Re-exploration was done within 48 hours after optimization of the patient’s physiology, which allowed us to reassess the bowel condition and performed a bowel anastomosis. The course of recovery, albeit being long, did not deviate from the expected progress in view of the initial presentation. The risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancy occurred in up to one-third of the patients and is associated with high maternal and perinatal morbidity (8). Future pregnancy is still possible and with favourable outcomes, provided with good tertiary level antenatal follow up and planned delivery via caesarean section are given (9).

In Malaysia, abortion is a highly sensitive issue that is tied closely to social, religious, and cultural values. Despite permissive laws relating to abortions being available in Malaysia, there are barriers in accessing safe abortion such as stigmatization, poor availability of services, high costs, conscientious objection of medical practitioners, and lack of adequate public information (2). Women with unwanted pregnancy often resort to unsafe abortion when access to safe abortion is difficult, with some resorting to self-induced abortion.

Based on a report by the Reproductive Rights Advocacy Alliance Malaysia (RRAAM), there are about 240 private clinics in Malaysia that offer abortion services, but not all are well regulated in terms of safety and fees (10). The cost of abortion can reach up to USD 800, which is unreasonably high. The cost is more than an average monthly wage in our country, which is around USD762. Women who come from a poor socioeconomic status or foreign migrant workers may not be able to afford such costs for abortion, hence turn to unsafe abortion. Moreover, abortion access in public health centers is limited, as many medical practitioners are unaware of abortion legalities in the country (2).

The lack of awareness among women regarding safe abortion may be attributed to limited and inadequate public information (11). Women are unaware of abortion legalities, and are unable to make an informed decision regard an abortion. Furthermore, social, religious and cultural stigmatization against abortion refrains woman from seeking safe abortion services (11).

Fortunately, the Ministry of Health published the first national guideline on the termination of pregnancy in government hospitals regarding the issues of induced abortion in 2012 (12). The guideline streamlines standardized management of termination of pregnancy, pre-termination, post-termination management, methods of termination and religious perspectives. A well-established guideline is a small step in improving accessibility to safe abortion services in Malaysia. It needs to be translated into clinical services. However, to date, little change has been made in order to make abortion services available in the government sector (10). Thus, awareness of safe abortion remains low among Malaysians (10). Furthermore, misoprostol and mifepristone have been used for medical abortion with high efficacy and good safety profile (12). Effective rate for complete abortion can up to 95% in early pregnancy. However, both mifepristone and misoprostol are not registered in Malaysia for this purpose (12), even though both drugs have been listed in 21st WHO essential medicines list since July 2020 with the aim to prevent unsafe abortion and reduce maternal death (13). Nevertheless, medical advice should be sought prior use of these medication. Registration of such medications to be used in hospital should be given consideration and proper regulation should be paid attention to prevent illegal trading of these medication.

More effort should be carried out by health authorities to achieve accessible safe abortion services, and reduce public stigmatization. Both require a collaboration of effort between the government and women/health non-profit organizations, welfare departments, and medical and nursing schools (2). Adequate training, well-equipped facilities, awareness campaigns and education should be taken into account as well. If intervention is not done, unsafe abortion can lead to major social and financial costs for women, families, communities and health systems in the long run.

Conclusions

Unsafe abortion is a serious public health concern, with significant mortality and morbidity rates. Prompt diagnosis and early surgical treatment in uterine and bowel perforation help to improve patients’ overall outcome. The application of a damage control strategy in hemodynamics compromised patients may improve the anastomosis rate. Factors that prelude safe abortion include stigmatization, poor access to services, high costs, conscientious objection of medical practitioners and lack of adequate public information. Collaborative efforts from the relevant authorities are crucial to ensure the availability of safe abortion services, health education, facilities, training and awareness campaigns.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank all the efforts provided by general surgery team and ICU team from Hospital Sultanah Aminah, Johor Bahru.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-21-46/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-21-46/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jphe.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jphe-21-46/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing unsafe abortion. 25 Sept 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preventing-unsafe-abortion.

- Low WY, Tong WT, Wong YL, et al. Access to safe legal abortion in Malaysia: women's insights and health sector response. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:33-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alam I, Perin Z, Haque M. Intestinal perfortion as a complication of induced abortion a case report review of literature. Faridapur Med Coll J 2012;7:46-9. [Crossref]

- Mabula JB, Chalya PL, Mchembe MD, et al. Bowel perforation secondary to illegally induced abortion: a tertiary hospital experience in Tanzania. World J Emerg Surg 2012;7:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sama CB, Aminde LN, Angwafo FF 3rd. Clandestine abortion causing uterine perforation and bowel infarction in a rural area: a case report and brief review. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oludiran OO, Okonofua FE. Morbidity and mortality from bowel injury secondary to induced abortion. Afr J Reprod Health 2003;7:65-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sohn M, Iesalnieks I, Agha A, et al. Perforated Diverticulitis with Generalized Peritonitis: Low Stoma Rate Using a "Damage Control Strategy". World J Surg 2018;42:3189-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Usta IM, Hamdi MA, Musa AA, et al. Pregnancy outcome in patients with previous uterine rupture. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:172-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chibber R, El-Saleh E, Al Fadhli R, et al. Uterine rupture and subsequent pregnancy outcome--how safe is it? A 25-year study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:421-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International campaign for women’s right to safe abortion. Feature: The law, trials and imprisonment for abortion in Malaysia. 11 July 2018. Available online: https://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/news/feature-the-law-trials-and-imprisonment-for-abortion-in-malaysia/

- Tong WT, Low WY, Wong YL, et al. Exploring pregnancy termination experiences and needs among Malaysian women: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:743. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Guidelines on Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) for Hospitals in the Ministry of Health. Putrajaya, Malaysia. Ministry of Health Malaysia 2012.

- WHO electronic Essential Medicines List (eEML), World Health Organization 2020. Available online: https://list.essentialmeds.org/ (beta version 1.0).

Cite this article as: Chuah JS, Kumar RRN, Goh YP. Emergency surgery for uterine and bowel perforation resulting from an illegal induced unsafe abortion: a case report. J Public Health Emerg 2022;6:9.